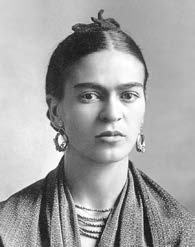

Everybody loves Frida Kahlo…now. Barely 60 years after her death, she and her art have inspired over 65,000 web sites, hundreds of books and articles, documentaries, movies, and fashions. Reproductions of her work are found on more than 2,000 household items, including mouse pads, coffee mugs, and throw pillows. In 2001, she became the first Hispanic woman honored on a U.S. postage stamp. A patron saint to many minority and often marginalized groups—lesbians, gays, feminists, bisexuals, people with disabilities, Chicanos, Communists, and others—she is studied, analyzed, idealized, and adored.

Everybody loves Frida Kahlo…now. Barely 60 years after her death, she and her art have inspired over 65,000 web sites, hundreds of books and articles, documentaries, movies, and fashions. Reproductions of her work are found on more than 2,000 household items, including mouse pads, coffee mugs, and throw pillows. In 2001, she became the first Hispanic woman honored on a U.S. postage stamp. A patron saint to many minority and often marginalized groups—lesbians, gays, feminists, bisexuals, people with disabilities, Chicanos, Communists, and others—she is studied, analyzed, idealized, and adored.

That she was not so cherished and embraced during her life is manifested in her art. Almost all of it portrays her sad feelings about herself and the impact upon her, through their love or betrayal, of those she knew well. As her husband, famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, said, “Frida is the only example in the history of art of an artist who tore open her chest and heart to reveal the biological truth of her feelings. [She is] the only woman who has expressed in her work an art of the feelings, functions, and creative power of woman.” Her truth has made her immortal.

She did not originally think to become an artist. A survivor of undiagnosed polio as a child, Kahlo planned to become a physician. At the age of 18, however, she was seriously mangled in a bus accident in Mexico City. She spent over a year in bed recovering from her injuries and suffered physical grief for the rest of her life. During her convalescence, she began to paint, “to combat the boredom and pain,” she said, “without giving it any particular thought.” Except for a few art classes in high school, she had no formal training.

She did not originally think to become an artist. A survivor of undiagnosed polio as a child, Kahlo planned to become a physician. At the age of 18, however, she was seriously mangled in a bus accident in Mexico City. She spent over a year in bed recovering from her injuries and suffered physical grief for the rest of her life. During her convalescence, she began to paint, “to combat the boredom and pain,” she said, “without giving it any particular thought.” Except for a few art classes in high school, she had no formal training.

Born in 1907, she was 22 years old when she married Rivera, the “Michelangelo of Mexico,” 20 years her senior. It was under his tutelage that she brought indigenous Mexican art into both her work and her life. She began painting in a deliberately primitive style, using bright colors and folk symbolism, while dressing in the traditional clothing of the Tehuantepec Peninsula and arranging her hair in time-honored ways. Eventually, across more than 150 paintings, she created a powerful narrative that merged elements of symbolism, fantasy, and folklore to share deep, personal feelings.

Born in 1907, she was 22 years old when she married Rivera, the “Michelangelo of Mexico,” 20 years her senior. It was under his tutelage that she brought indigenous Mexican art into both her work and her life. She began painting in a deliberately primitive style, using bright colors and folk symbolism, while dressing in the traditional clothing of the Tehuantepec Peninsula and arranging her hair in time-honored ways. Eventually, across more than 150 paintings, she created a powerful narrative that merged elements of symbolism, fantasy, and folklore to share deep, personal feelings.

The relationship between her and Rivera eventually became a stormy one, but all that was in the future when, in 1930, the newlyweds visited San Francisco. He had been commissioned to create murals for the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts. During her own time, she painted Frieda and Diego Rivera, based upon their wedding picture. Included in 1931’s Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists—the first public showing of her work—one local newspaper described it as “valuable only because it was painted by the wife of Diego Rivera.” Now part of the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, nobody imagined that one day her reputation and importance as an artist would transcend that of her husband.

Kahlo and Rivera separated in the summer of 1939, partly because of the sexual adventures each pursued. By the time they again visited San Francisco in 1940, they had been divorced for a year. He came to paint Pan American Unity, a 75-by-22-foot mural now on display at the City College of San Francisco. On Sunday, December 8, they remarried at San Francisco City Hall. The rapture was short lived, however, although their union, living together or apart, lasted until Kahlo died in 1954.

Painting became her salvation. Enduring 32 operations in 30 years for her injuries, bedridden for months at a time, and often betrayed by her husband’s infidelities, she used her art to reveal the physical and emotional anguish that she lived with for most of her life. As Janet Landay, curator of exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, explained, “Kahlo made personal women’s experiences serious subjects for art, but because of their intense emotional content, her paintings transcend gender boundaries. Intimate and powerful, they demand that viewers—men and women—be moved by them.” Not only does she enable us to see what she saw, she compels us to feel what she felt.

By allowing us to peer through her paintings into her psychological state, her heart and soul, Kahlo reaches out through her work to bring us into a mutual, shared world. We feel the emotions surrounding her pain and misery, her melancholy and regret for the human condition. Although, for her, existence was physical suffering and emotional sorrow was the failure of the body and the duplicity of love, she tells us that life can succeed despite great and constant adversity. Through her art, she shows us her humanity. That we care shows us ours.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments