By Gary M. Kramer –

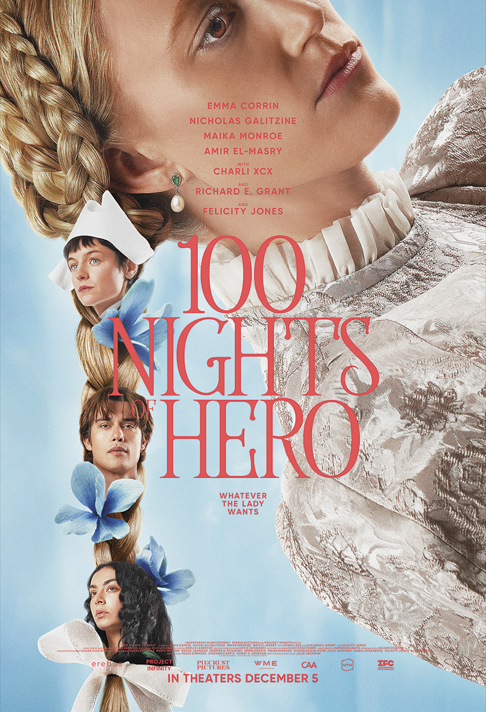

Queer writer/director Julia Jackson (Bonus Track) has crafted a stylish and clever queer romance with 100 Nights of Hero. The film, opening in area theatres December 5 and adapted from Isabel Greenberg’s graphic novel, The One Hundred Nights of Hero, is set in a fictional medieval land where a woman’s place is to marry and have sons, not to read or write.

This arch film recounts the story of Cherry (Malika Monroe), who is being pressured to have a son with her husband, Jerome (Amir El-Masry). Alas, Jerome “prefers to hunt and ride, and play darts with his handsome friends rather than spend time in the bedroom with his wife.” Enter Manfred (Nicholas Galitzine), a rake who bets Jerome that he can seduce Cherry, whom Jerome insists is a “paragon of virtue.” One obstacle to Manfred’s plan is Cherry’s handmaiden, Hero (Emma Corrin), who is happy to distract Manfred by telling stories. The story-within-the-film is a feminist tale about Rosa (Charli XCX) resisting a marriage.

100 Nights of Hero has great fun as Hero teaches Cherry how to kiss and Manfred tries to weasel his way into Cherry’s bedroom. The costumes and set design are fabulous and the cast delivers the witty dialogue with aplomb. Jackson spoke with me for the San Francisco Bay Times about making her fabulous fairytale.

Gary M. Kramer: The film is about women telling stories to save themselves and start a revolution. What can you say about (re)telling the stories in 100 Nights of Hero?

Julia Jackson: Creating this impression of a population that has been waiting for a spark for a long time is a challenge. I loved this idea of Isabel taking inspiration from One Thousand and One Nights, and making this graphic novel, and I took inspiration from that and made a film. There is a progression of stories of women talking to each other and essentially comparing notes. The thread for me was how crucial it is to keep communicating with each other in a world that doesn’t necessarily want people to be sharing or controlling information.

Gary M. Kramer: What approach did you take to adapting the beloved graphic novel?

Julia Jackson: Preserving the heart of the graphic novel—its playfulness and its revolutionary heart—was really important to me. The novel was quite anthological. I ended up fleshing out much of the main storyline. You spend less time with Cherry and Hero and Manfred in the graphic novel. They are fixed in their roles; Cherry and Hero are already a secret couple and Manfred is an old, dastardly villain. In the spirit of Isabel’s sense of camp, I leaned into this fluidity, and how much society tries to impose these structures. The most macho men have an air of homoeroticism and attraction between them.

Cherry and Hero’s love story and intimacy was incredibly important, but I wanted to start them in that classic queer coming of age state, where you have this best friend whom you think is incredible and beautiful, and you want to spend all your time with them but you don’t recognize that feeling as being in love until later—especially in a world that tells you that it is wrong, or forbidden. But the forbidden-ness can make it more exciting and scarier. This queer forbidden love has intimacy first that builds to attraction and queer yearning and the feeling of not even allowing yourself to want something because you are so sure you can’t have it. That was where I wanted them to start—in love and in denial as opposed to fully together.

Gary M. Kramer: What decisions did you make with creating the tone of the film?

Julia Jackson: That was something that is different on screen. It was present in the graphic novel. Isabel had this playfulness and wit to her writing that was often quite deadpan, so, by the time the sincerity and emotion and anger came in, you felt that it snuck up on you in this way. It has always been a tricky tone—as in challenging, as in tricky, where what you think you are watching changes throughout. I leaned into that and the idea that Hero takes this direction, if the story itself is about this underestimated person lulling people into a scenario by appealing to what they think it’s going to be. Isabel’s graphic novel has that meta element, but it was definitely pumped up in the film. You have this feeling it’s going to be this really steamy love triangle. Manfred thinks he’s going to seduce this woman and keep a castle and he’s just listening to another woman talking. There is that slipperiness intrinsic in the scheme as well.

Gary M. Kramer: The film has a distinctive look, with amazing costumes, set design, and imagery. Can you talk about the world-building?

Julia Jackson: Obviously massive kudos to Susie Coulthard and Sophia Sacomani, our costumes and production designer, respectively, and to Paul Rice, our visual effects supervisor who created the stained glass and the moons. The costumes were custom-made by Susie and her team. I had a mood board, and my main inspiration was the silly hats, which were camp and pointed to this idea of the theatricality of roles people are expected to play in society. But I wanted it to feel a little bit more out of time and more gothic than the graphic novel. It was interesting to see what was possible.

Gary M. Kramer: There is a very queer bent here, with Jerome being clocked as queer, and Hero teaching Cherry how to kiss. What can you say about playing the queer content up or down? It is both overt and subversive.

Julia Jackson: A litmus test for me is that I can tell who laughs when Cherry and Hero say they are “best friends.” I feel the gays intrinsically understand that right away. Some take it at face value. The graphic novel doesn’t have any sex in it at all. I respected the yearning quality of it, but I did want to pump it up a little bit. It felt to me, especially as with a lot of lesbian stories, there is this idea there is going to be a lot of hand brushing and then suddenly people are furiously scissoring. It wasn’t about shame or what the characters themselves felt, but it was in a world without freedom, and I wanted to pump up the horniness while honoring the fact that this is a story of people who were never taught to act on their desires and the stakes were high if they did. In the end, I shot one full sex scene, and I put it in the sky in the end with this idea: Is it a flashback, or what they would do if they were together?

Gary M. Kramer: The film is about women fighting the patriarchy and the rules of society, to become educated and empowered. Cherry is supposed to get married, have children, do needlepoint and then die. Knowing Hero and hearing her stories makes her wish she lived a braver life. Why do you think this message still resonates today?

Julia Jackson: I hope that it would say to people that the powers that be are going to push people who historically have been on the margins back into the margins. I hope it shows that, when we keep talking and have each other’s backs and keep insisting on having a seat at the table—whether it is what we are allowed to know, allowed to see, or the public spaces we are allowed to inhabit—you don’t give that up, that we keep talking to each other. People are going to try to make you feel like you are alone and ashamed, and you’re not. The biggest tool they have is if people are isolated from each other. It’s a rallying call against that shame and self-isolation.

© 2025 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” He teaches Short Attention Span Cinema at the Bryn

Film

Published on December 4, 2025

Recent Comments