In an era when American taste-makers applauded verse that described a doe as “a deer, a female dear,” Allen Ginsberg, just 30 years old, published his first book, Howl and Other Poems, in 1956. An impassioned, unsparing wail of anguish about “the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” by conformity and by the norms of middle-class society, it simply was not everybody’s cup of tea (a drink with jam and bread).

In an era when American taste-makers applauded verse that described a doe as “a deer, a female dear,” Allen Ginsberg, just 30 years old, published his first book, Howl and Other Poems, in 1956. An impassioned, unsparing wail of anguish about “the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” by conformity and by the norms of middle-class society, it simply was not everybody’s cup of tea (a drink with jam and bread).

Almost immediately, the guardians of other people’s propriety set upon the work and those who believed in it. First, customs officials impounded the poem’s second printing when it arrived in San Francisco. The United States district attorney declined to begin condemnation proceedings, so the books were released to their owners. Next, an undercover police officer bought a copy, then arrested and jailed Shig Murao, manager of City Lights bookstore, for selling him obscene literature. Poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti later was arrested for publishing it.

At the subsequent obscenity trial, the defense argued simply that it was “not the poet but what he observes which is revealed as obscene.” The Court decided the work had “redeeming social importance;” the accused were found not guilty. At that point, previously censored works, including Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover, could be sold in the United States. They were and to great acclaim. Eventually, the ruling became a precedent for the United States Supreme Court when it established the criteria to determine if a publication can or cannot legitimately be subject to state regulation.

Now considered to be one of the greatest American poems ever written,“Howl” became “the mantra of a generation” caught up in a society being shaped by the cookie cutters of modern times. Translated into more than twenty-two languages, it was among the most widely read poems of the 20th century. Although most poets are known only to a few admirers, Ginsberg, like Walt Whitman before him, was familiar to millions who had not read any of his poetry.

Now considered to be one of the greatest American poems ever written,“Howl” became “the mantra of a generation” caught up in a society being shaped by the cookie cutters of modern times. Translated into more than twenty-two languages, it was among the most widely read poems of the 20th century. Although most poets are known only to a few admirers, Ginsberg, like Walt Whitman before him, was familiar to millions who had not read any of his poetry.

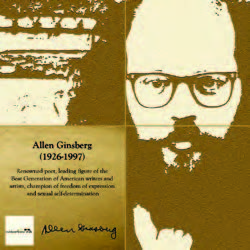

Ginsberg simply overwhelmed the Babbittry and ticky tacky of his generation. In an era of button down shirts and buttoned up minds, he was openly homosexual—when it was illegal in every state. Born into a Jewish family in Newark, New Jersey, in 1926, he died a Buddhist in New York City in 1997. During an era of cold war, “red scares,” loyalty oaths and enforced conformity, he was an outspoken advocate of free speech and free love, peace, and the unconventional. He believed in the importance of individual thoughts and experiences, and in the founding principle that democracy begins with the raising of a single voice.

Throughout his life, Ginsberg refused to accept the dominant, acquiescent, materialistic culture without question. As a founding member of the Beats, his generation’s most influential literary movement, and later as the self-proclaimed “old auntie of the Beat Generation,” he valued art above money, peace above conflict, free love over monogamy (or monotony, as he put it), and poetry above all. He

expressed himself and his philosophy of art, spiritualism, and the value of the individual human mind not only as a poet, but also as a photographer, songwriter, teacher, and philosopher.

He also expressed his principles as a political activist. In 1968, already world famous, Ginsberg travelled to Chicago to protest against America’s war in Vietnam. When Chicago police attacked demonstrators in the city’s Grant Park with tear gas and billy clubs, he took to a jury-rigged stage in an effort to calm the crowd. In the early 1970s, his photograph appeared on one of the most widely distributed posters protesting the war, showing him with a Walt Whitman beard, black-rimmed glasses, and an “Uncle Sam” paper top hat. He was at that point one of the most revered spokesmen of the next generation of radicalized Americans, known as “Hippies,” despite the warning, “Never trust anybody over 30.”

By the 1980s, Ginsberg was America’s most famous living poet. Even so, he was never awarded a Pulitzer Prize. (In 1995, the sole time he was nominated, it went to Philip Levine.) Ginsberg seemed not to care. In an age of conspicuous consumption, he continued to live modestly in rented apartments, buying his clothing in thrift stores.

As the literary critic Helen Vendler wrote, he remained “tirelessly persistent in protesting censorship, imperial politics, and persecution of the powerless.” Even now, almost 60 years after “Howl” was found to have “redeeming social value” by the Court, its content and language still can create problems for broadcast radio and television stations in the United States, should they choose to air it.

How did Ginsberg want to be remembered? “As someone in the tradition of the old time American transcendentalist individualism,” he once said, “from that old gnostic tradition—Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman—just carrying it on into the 20th century.” Ginsberg, champion of the freedom of thought and expression, individuality, and sexual self-determination, continued that tradition all his life.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments