By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

We, like millions of Americans, were deeply disturbed and disillusioned by the U.S. Senate’s confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. And as we’ve previously discussed in this column, the fear that Kavanaugh—who replaced Justice Kennedy, author of all the Court’s landmark gay rights decisions—could undermine LGBTIQ rights for a generation is unsettling, to say the least.

Kavanaugh may be put to the test very soon. Indeed, in the current 2018–2019 term, three cases the Court could hear concern an issue of enormous nationwide importance: whether Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and/or gender identity as unlawful sex discrimination covered by the Act.

The first case the Court could take is Bostock v. Clayton County and pertains to Gerald Bostock, the former Child Welfare Services Coordinator for the Clayton County Georgia Juvenile Court System. Bostock claims that he was fired on trumped up charges when the County learned he was gay. Bostock’s Supreme Court petition describes him as “a dedicated social services professional who has for many years been committed to ensuring that abused and neglected children have safe homes in which to live and grow.” A three-judge panel of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals threw out his case because it held that Title VII does not prohibit employers from terminating employees because they’re gay. Bostock asked the high court to hear his case.

The second case, Altitude Express v. Zarda, raises the same issue and was filed on behalf of Donald Zarda, a now-deceased New York skydiving teacher who alleged that he was fired from his job for being openly gay. Last year, the Second Circuit en banc (meaning all judges of that appellate court, not just a typical 3-judge panel) reached the opposite conclusion to the Eleventh Circuit, allowing Zarda’s case to go forward and holding that Title VII prohibits dismissing an employee based on sexual orientation. (Last year, the Seventh Circuit en banc reached the same conclusion.)

The Supreme Court was scheduled to discuss whether or not to take the Bostock and/or Zarda cases at its September 24 internal conference, but postponed the question probably, in part, because of the vacancy on the Court and possibly because of a third pending case, briefing of which should be completed this fall.

The third case, Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC, was brought by Aimee Stephens, a funeral director at Harris Funeral Homes, who was fired after she informed her employer that she was transgender and would be transitioning. The Sixth Circuit held that Title VII proscription on sex discrimination prohibited Stephens from being fired based on her gender identity. The funeral home seeks Supreme Court review of the decision.

The federal circuit courts have diverged significantly as to the scope of Title VII’s application to sexual orientation and gender identity, two related but different issues. We don’t know whether the Court will take up either or both issues or leave them for another day, giving time for other circuit courts to issue additional opinions or for Congress to amend Title VII to include sexual orientation and gender identity explicitly.

In dissenting from the Eleventh Circuit’s refusal to reconsider the Bostock case en banc, Judge Robin Rosenbaum termed earlier circuit court cases holding that Title VII did not apply to sexual orientation as having “the precedential equivalent of an Edsel with a missing engine”—referring to the late 1950s monumental flop of a car sold by the Ford Motor Company.

At Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing, Senator Cory Booker asked him whether it would be wrong to fire someone because they’re gay. Kavanaugh volunteered only, “In my workplace, I hire people because of their talents and abilities. All Americans.”

Booker pressed: “There are a lot of folks who have concerns that if you get on the court—folks who are married right now really have a fear that they will not be able to continue those marital bonds. We still have a country where, if you post your Facebook pictures up of your marriage to someone of the same sex, we still have a majority of the states where if that employer of yours finds out that you’ve got a gay marriage and that you’re gay, in the majority of America states, you can fire somebody because they’re gay.”

Kavanaugh refused to respond to the concerns directly, citing the pending cases that he might be in a position to decide.

In response to questioning from Senator Kamala Harris as to whether he believed Obergefell, the Court’s nationwide marriage equality decision, was correctly decided, Kavanaugh refused to answer, but declared that the Court had decided that “the days of discriminating against gay and lesbian Americans, or treating gay and lesbian Americans as inferior in dignity and worth, are over … . That’s a very important statement.”

Many are skeptical of Kavanaugh’s commitment to that statement when it comes to specifics—and more fundamentally agree with former Justice John Paul Stevens that Kavanaugh should not even be on the Supreme Court. But like it or not, Kavanaugh likely holds the deciding vote on whether Title VII protects LGBTIQ people from being fired because of their sexual orientation or gender identity if the Court takes up the issue. Now is the time to do everything we can to hold him to his words.

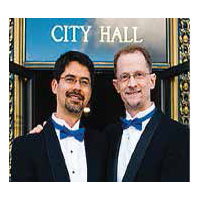

Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Recent Comments