By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

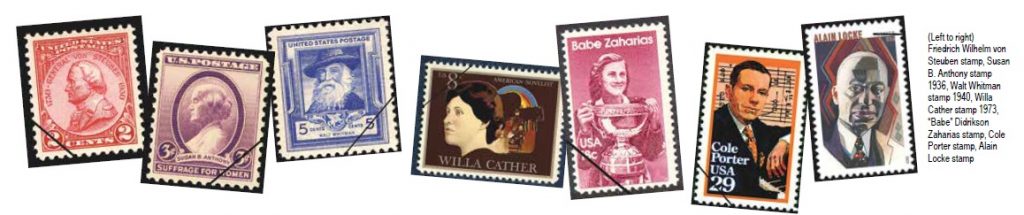

As we remember the 50th anniversary of the first pride celebrations and the daring people who made them possible, we also take pleasure in the accomplishments of a unique group of LGBT Americans: those recognized with a stamp issued by the United States Postal Service. From the first in 1930 to the most recent only last month, here are a few of the several dozen men and women honored so far. Probably we will never have a complete list of them all.

1930

Whatever else may be said about him, Baron Friedrich von Steuben (1730–1794) loved his fellow man. After reforming and modernizing the army of Frederick the Great of Prussia, he was forced into exile for allegedly becoming too close to some of the young men under his command. He then was offered the position of inspector general of the Continental Army, which he accepted, serving directly under George Washington.

Steuben arrived at Valley Forge in February, 1778, the winter of despair for the American Revolution, with his French cook; aide-de-camp; miniature greyhound; seventeen-year-old personal secretary and companion; and others. As poorly as he spoke English, he shaped the disarrayed Continentals into an organized and effective fighting force. His Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, written in 1779, remained the country’s official military handbook until 1812.

While at Valley Forge, Steuben entered into “extraordinary intense emotional relationships” with two military officers, then in their 20s. After the war, he legally adopted them both. When the Baron died, they inherited the bulk of his estate. He left a third young man, who also considered himself a “Steuben son,” his books, maps, and $2,500 in cash, then a considerable amount.

1936 and 1954

One of the very few women not the wife of a president to be honored more than once on a U.S. postage stamp, Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) devoted her life to achieving equal rights for those who did not have them. When she was only 17 years old, she circulated anti-slavery petitions and in 1863 co-founded the Women’s Loyal National League, which gathered some 400,000 signatures to support slavery’s abolition. She remained a leader in the struggle for racial equality for decades.

In 1869, Anthony and her close friend and colleague Elizabeth Cady Stanton founded the American Woman’s Suffrage Association. After years of writing, speaking, and organizing, they persuaded Sen. Aaron A. Sargent (R-CA) to introduce legislation in Congress to confer upon women the right to vote. In 1920, what is still known as the Anthony Amendment finally became part of the U.S. Constitution, doing just that. It has been her great, living monument for the past hundred years.

Perhaps Anthony’s most intense and long-lasting relationship was with actor and orator Anna Dickinson, the first woman to give a political address before the U.S. Congress. In their letters, Anthony addressed her as “My Dear Darling Anna,” “Dearly loved Anna,” and “Dear Chick a dee dee.” In one she wrote that she hoped “to snuggle you darling closer than ever.” In another she invited her to “share my … bed,” assuring her it was “big enough and good enough to take you in.”

Some historians explain that in a more flowery and sentimental age these words had a different meaning than they do now, expressing only deep affection, not passionate intimacy. As we discover more and more about the past, however, we find that people then had amorous feelings toward each other, just as they do now, and said exactly what they meant to say.

1940 and 2019

Walt Whitman (1819–1893), America’s greatest poet, who critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold accused in a November 1855 review of being guilty of “that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians,” believed in “comradeship” or “adhesive love,” the unifying ability of love between men. After he met him in 1882, Oscar Wilde told pioneering homosexual-rights activist George Cecil Ives, “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.” Ives understood completely.

1973

Novelist, short story writer, and Pulitzer Prize winner Willa Cather (1873–1947) knew from an early age who she was. Even as a student at the University of Nebraska in the early 1890s, she cut her hair short, wore men’s clothes, and sometimes referred to herself as “William.” Her most enduring relationship was with editor Edith Lewis, with whom she lived the last 39 years of her life.

1981

Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias (1911–1956) got her nickname “Babe” for Babe Ruth after she hit five home runs in a childhood baseball game. Adept also at basketball, tennis, and bowling, she excelled at golf, winning 82 tournaments between 1933 and 1953, 17 of them consecutively in 1946–1947. Long considered the finest woman golfer of all time, in 1999 both the Associated Press and ESPN named her the greatest woman athlete and one of the 10 greatest athletes of the 20th century.

1991

Only lyricist and composer Cole Porter would dare write a Broadway showstopper ending, “But if, baby, I’m the bottom you’re the top!” or, “A dicka dick, A dicka dick, A dicka dick!” Only he would tell listeners, “Experiment/Be curious/Though interfering friends may frown, Get furious/At each attempt to hold you down/The future can offer you infinite joy/And merriment/Experiment.” Fellow LGBT songwriter Lorenz Hart (1895–1943), honored in 1999, was never so bold.

2020

Often heralded as the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance” for The New Negro (1925), his landmark anthology of written and visual arts, educator and philosopher Alain Locke (1885–1954), the first African American Rhodes Scholar, taught at Howard University for more than 40 years. As a gay man, he encouraged—and pursued—other gay African Americans who became major figures of what was then known as the “New Negro Movement,” after his book, including Langston Hughes, Richard Bruce Nugent, and especially Countee Cullen.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on June 11, 2020

Recent Comments