By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

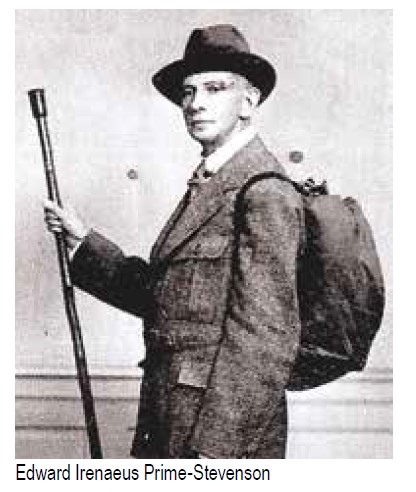

In Her Enemy, Some Friends, and Other Stories, published in 1913, Edward Prime-Stevenson (1858–1942) kindly provided his readers with a list of books to be found in a well-read homosexual’s lavender library at the turn of the 20th century. “Almost every man of like making-up,” he wrote, “had a special group of volumes … crowded into a few lower shelves, as if they sought to avoid other literary society, to keep themselves to themselves, to shun all unsympathetic observation.”

The list contained publications both immortal and obscure. In addition to Greek and Roman “antologists,” it included Michelangelo’s and Shakespeare’s homoerotic sonnets; Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which expressed the poet’s deep love for his friend Arthur Henry Hallam; The North Shore Watch by George Edward Woodberry; Horace Annesley Vachell’s The Hill, the story of two students at Harrow who compete for the love of a third; and Tim, published anonymously, “a delicate portrayal of a sensitive boy’s devoted affection for an older boy.”

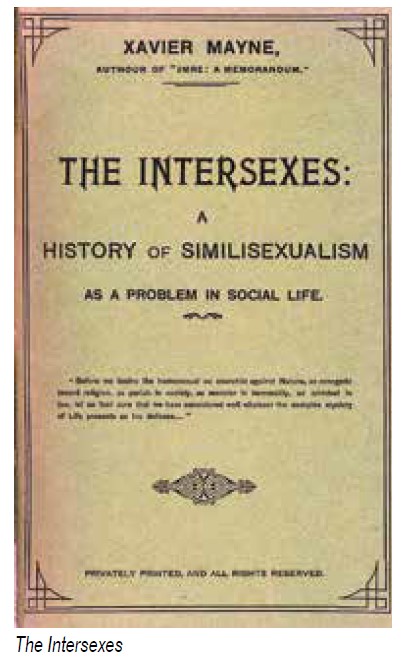

The only writer on the list with more than one book was Xavier Mayne, author of Imre: A Memorandum and The Intersexes: A History of Similisexualism as a Problem in Social Life—both groundbreaking works of enduring influence—and Sebastian au Plus Bel Age, a novel now presumed to be lost (if it ever existed anywhere except in this catalog of titles). What Prime-Stevenson did not tell his readers was that he and Mayne were the same person.

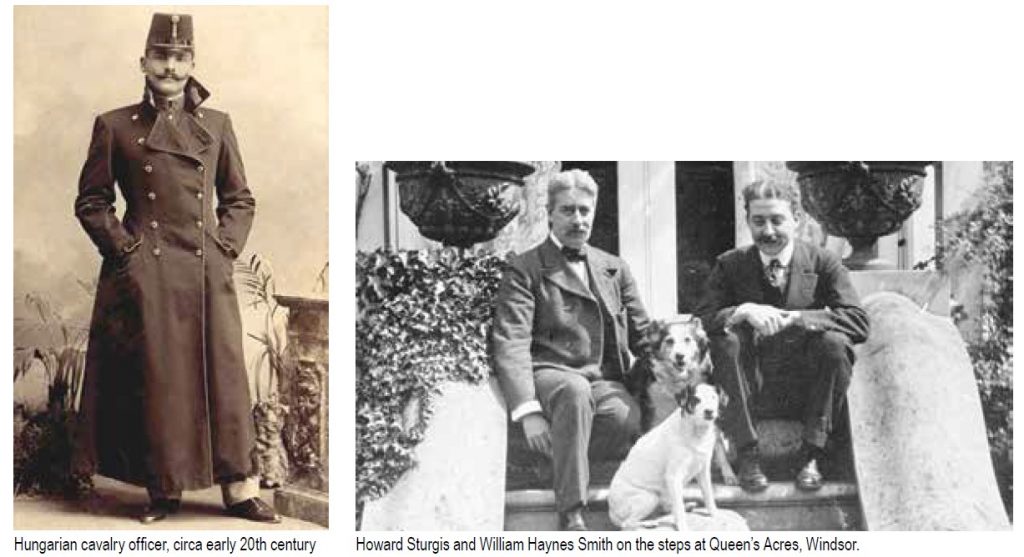

Imre was privately printed in Naples in 1906 as a “little psychological romance,” during an era when medicine was formalizing its view that homosexuality was an identifying pathology, not what many then believed was a sinful behavior or an acquired vice. It tells the story of the love affair between Oswald, a “past thirty” Englishman who is spending a summer in Budapest, and Imre, a 23-year-old Hungarian cavalry officer. Eventually they join together in “the friendship which is love, the love which is friendship.”

Prime-Stevenson’s goal, however, was not to write a romance with sensual encounters—there are none—but to describe how its heroes, “lovers of their own sex,” found each other; how they gradually told each other about their sexuality; and how, as a couple, they changed their ideas about themselves, which had been negative and self-loathing, to face an optimistic future together. It was the first novel by an American to give a happy ending to a story of two men in love with each other.

The author himself was less “lucky in love” than Imre. Although he almost certainly had intimacies before and since, the great romance of his life seems to have been with Harry Harkness Flagler, son of a co-founder of the Standard Oil Company, who became president of the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Society and the orchestra’s principle financial backer. Their “great and good friendship” ended in 1893, the year before Flagler married, although Prime-Stevenson continued to always care for him deeply.

Two years after Imre appeared, Prime-Stevenson published The Intersexes: A History of Similisexualism as a Problem in Social Life. As the pioneering survey of homosexuality in Europe and America, it is one of the foundational works of modern LGBT studies. “Before we loathe the homosexual as anarchist against Nature, as renegade toward religion, as pariah in society, as monster in immorality, as criminal in law,” he wrote, “let us feel sure that we have considered well whatever the complex mystery of Life presents as his defense.”

To provide the historical, legal, and scientific context for that defense, Prime-Stevenson read almost everything then available about homosexuality. He interviewed physicians, psychiatrists, and workaday people from many different backgrounds. His conclusions, then not generally accepted socially or scientifically: homosexuality was neither an abnormality nor a disease. It was, in fact, inborn, a normal and natural temperament. “Temperamentals,” as they were often called then, might face social and legal persecution, but they could not and should not be other than who they are.

For Prime-Stevenson, similisexualism was “a problem in social life” because the medical profession had made it a problem and society had made it illegal. He knew the difficulties very well, which is why he used a pseudonym to publish his books about homosexuality. Howard Overing Sturgis (1855–1920) went even further. For Tim, his first novel (1891), which he admitted on the title page was a story of the “love that surpasses the love of women,” he used the pen name “Anonymous.”

He probably worried for nothing.Published simultaneously in London, New York, and Leipzig, Tim was immediately successful. It tells the story of a sensitive young boy very much in love—emotionally and spiritually, of course, not sexually—with Carol, a boy a few years older, his best friend. When Carol meets the girl he will marry, Tim, out of his great affection, graciously steps aside to assure Carol’s happiness at the loss of his own, then wastes away like Werther lamenting his loss of Charlotte.

Nicknamed Howdie, Sturgis was “a delicate child, closely attached to his mother, and fond of such girlish hobbies as needlepoint and knitting, which he continued to practice throughout his life.” He became “a sturdily built handsome man with brilliantly white wavy hair, a girlishly clear complexion, [and] a black moustache.” His sexuality was not a secret to his friends, who included the deeply closeted novelist Henry James, although one intimate defended him by explaining, “There was ‘nothing effeminate about his execution of female tasks.”

Howdie’s life companion was William Haynes-Smith (1871–1937), known as “the Babe,” son of an English colonial administrator. In 1888, the two men moved into a country house they called, without a hint of irony, Queen’s Acre; they lived there as a couple for more than 30 years. Four years after Sturgis died in 1920, Haynes-Smith married his niece Alice. Both were in their 50s. If not as happy together as Howdie and the Babe had been, hopefully they were content.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on October 22, 2020

Recent Comments