By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

When 20-year-old Richard Barnfield published The Affectionate Shepherd in 1594,he scandalized and outraged public propriety with his explicitly homosexual versifying. With exquisite poetic detail, his work described the deep feelings of love that Daphnis had for Ganymede, “that faire boy that had my hart intangled,” convention, morality and the law be damned. “If it be sinne to love a lovely lad,” he wrote, “Oh then sinne I, for whom my soule is sad.”

Although he was following the traditions of Greek and Roman pastoral poetry, including its celebration of handsome young men, Barnfield was neither subtle nor coy about the subject of The Affectionate Shepherd. He not only states on the title page that his is a work “containing the complaint of Daphnis,” whom he later identifies as himself, “for the loue [love] of Ganymede,” but he also makes clear that he is attracted to Ganymede not by his spiritual perfection, but by his physical beauty:

Whose amber locks trust up in golden tramels

Dangle adowne his lovely cheekes with joy,

When pearle and flowers his faire haire enamels.

Ganymede does not respond to Daphnis’ ardent courtship, not because he disapproves of same-sex intimacy, but because unrequited love is part of the pastoral literary tradition. Even so, his disinterest does not a happy poet make:

“Oh would to God he would but pitty mee,

That love him more than any mortall wight!

Should his readers have any doubt about Daphnis’ true feelings and desires, Barnfield uses specific and frankly erotic language to describe his great passion—and his intentions—as more than merely affectionate:

“O would to God, so I might have my fee,

My lips were honey, and thy mouth a bee!

Then shouldst thou sucke my sweete and my faire flower,

That now is ripe and full of honey-berries;

Then would I leade thee to my pleasant bower,

Fild full of grapes, of mulberries, and cherries:

Then shouldst thou be my waspe or else my bee,

I would thy hive, and thou my honey, bee.”

Barnfield’s audience would have understood both his intent and his meaning. In addition to the metaphor of bees gathering honey and the offer to “sucke my sweete and my faire flower,” any educated middle or upper-class Englishman would have known who Daphnis and Ganymede were and what they symbolized. As boys they received a classical education that included Latin, the language of Europe’s educated, and the works of the great Greek and Latin authors.

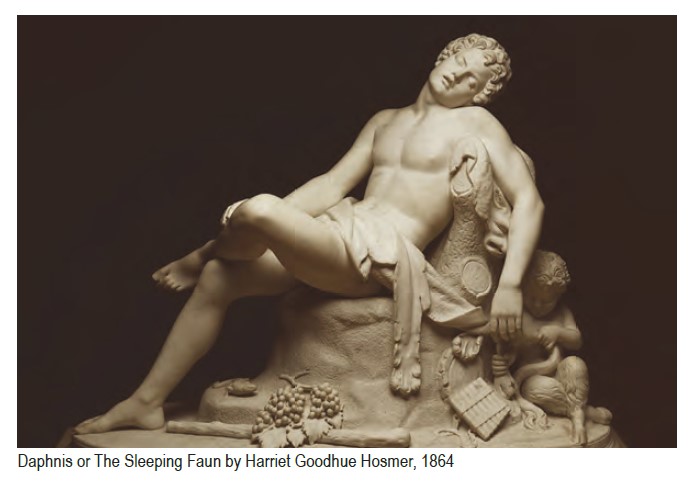

In the old myths and legends they studied, Daphnis, the son Hermes, was a handsome Sicilian shepherd renowned as the inventor of pastoral poetry. He was beloved by Apollo and romanced by Pan, who taught him to play the pipes. Although said to be involved in a love triangle with the nymph Nomia and her rival Chimaera, the daughter of a king, writers and artists often described and depicted him as an eromenos, the younger lover of an older man.

Ganymede had an even closer association with men who loved men. Taken up to Mount Olympus by Zeus, he served the gods as their cupbearer during the day and serviced the king of the gods at night. Known as Catamitus to the Romans, during Barnfield’s lifetime and for many years after, according to the Glossographia Anglicana Nova, first published in 1707, both “Ganymede” and “catamite” signified “any Boy loved for Carnal Abuse, or hired to be used contrary to Nature.”

With its explicit content and apparent endorsement of male-male love, Barnfield’s work may have aroused the pleasure of some of his readers, but it also angered the keepers of other people’s morality. In the preface to his next book, Cynthia, with certain Sonnets, and the legend of Cassandra, published in January 1595, he explained that he merely was paying homage to the second Eclogue of Virgil, another pastoral poem where Daphnis wept for his unrequited love of a young man.

Barnfield regretted that some readers “did interpret The Affectionate Shepherd otherwise than in truth I meant, touching the subject thereof, to wit, the love of a shepherd to a boy.” Even so, he then presented them with even more explicitly homoerotic poemspraising the emotional and physical intimacy two men could know with each other:

Long have I long’d to see my love againe,

Still have I wisht, but never could obtaine it;

Rather than all the world (if I might gaine it)

Would I desire my love’s sweet precious gaine.

Very little is known about either Barnfield’s life or his career. The son a country gentleman, he was born at Norbury, Staffordshire, England, where he was baptized on June 13, 1574. When he was 15, he entered Brasenose College, Oxford, founded in 1509, graduating with a Bachelors of Arts degree in 1592. By 1594, he had moved to London, where he became a member of a literary world that included Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton, and William Shakespeare, whom he greatly admired.

With the publication of his first three books between February 1594 and January 1595, Barnfield became the first Elizabethan to address love poems to another man. (Shakespeare was the second.) In his writings, he also became the first to openly identify himself as a man who loved men. After his fourth and final work appeared in 1598, he returned to Staffordshire, where he died in 1620. No one knows why he stopped writing or whether he ever found his Ganymede.

The Affection Shepard, for all the archaic Elizabethan vernacular it uses to describe the passion of one man for his adored, tells a universal truth: heartache comes to anyone infatuated with another whose feelings are not returned. We may yearn to live with our beloved in a condo in the suburbs, not a laurel grove in a sylvan glade, but desire is as strongly felt today as it was in Barnfield’s England—or anywhere and during any era—and unrequited love is still a universal complaint.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on June 10, 2021

Recent Comments