By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

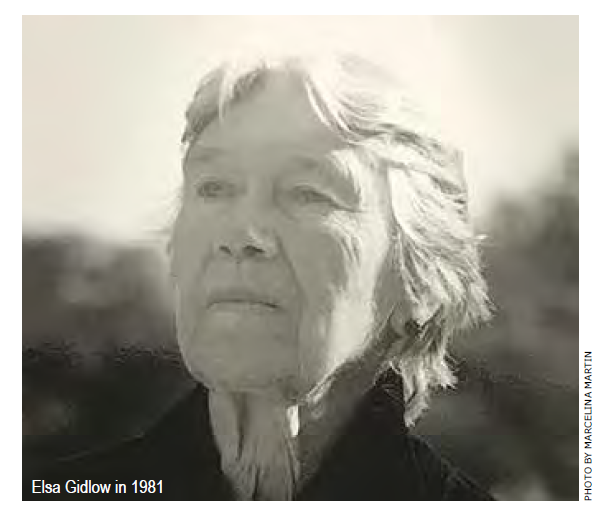

Elsa Gidlow lived her life as she wanted always: openly as an independent woman.

Poet, essayist, philosopher, and humanist, Gidlow wrote her first book, On a Grey Thread, in 1923, and it contained the first frankly lesbian love poetry published in the United States. It was not only written by and about a woman who loves women, but also one who identified herself as its author. Beginning with the “The Grey Thread,” the first in the collection, she described the different facets of her personal identity:

“My life is a grey thread,/A thin grey stretched out thread,/And when I trace its course, I moan:/How dull! How dead!/But I have gay beads./A pale one to begin,/A blue one for my painted dreams,/And one for sin,/Gold with coiled marks,/Like a snake’s skin.”

Unlike the poets of earlier generations (Tennyson, Whitman, Dickinson), who used coded language to describe their deep affection for those of their own gender, Gidlow made no secret that she was writing about women loving each other. Both her own sexuality and “the direction of emotional attention” in her poems were undisguised:

“Watch my Love in sleep:

Is she not beautiful

As a young flower at night

Weary and glad with dew?”

The beliefs Gidlow shared in On a Grey Thread were far ahead of their time and contrary to its fundamental, traditional values. Not only was she openly admitting her sexual orientation and publicly advocating for same-sex intimacy—both purple and green were colors associated with homosexuality—but she also endorsed open relationships:

“You’re jealous if I kiss this girl and that, You think I should be constant to one mouth? Little you know of my too quenchless drouth: My sister, I keep faith with love, not lovers.”

Born Elsie Alice Gidlow on December 29, 1898, in Hull, England, Gidlow with her family moved to Montreal, Canada, when she was 15. She knew who she was at an early age. In the fall of 1917, still only 18, she wrote a letter to the Montreal Daily Star and invited all interested individuals to join the first meeting of a writers’ club she was starting. Among those who attended was Roswell George Mills, who became the first “openly gay” Canadian.

According to Gidlow, “He was beautiful. About nineteen, exquisitely made up, slightly perfumed, dressed in ordinary men’s clothing but a little on the chi-chi side. And he swayed about, you know.” Mills considered it his personal crusade to make people “understand that it was beautiful, not evil, to love others of one’s own sex and make love with them.” Because they were both interested in poetry and the arts, the two became fast friends.

The year after they met, Gidlow and Mills founded Les Mouches Fantastiques (The Fantastic Flies), the first magazine published in North America not only to be written primarily by lesbians and gays, but also to discuss their concerns and to celebrate them in its poetry and articles. No more than 100 mimeographed copies of the early issues were produced, but those were passed from reader to reader. At least one reached an Episcopal priest living in South Dakota, who then moved to Montreal to become Mills’ lover.

Gidlow and Mills created five issues of the magazine before Gidlow moved to New York in 1920. Barely 21, she was seeking greater opportunity to live as she pleased. She changed her name to Elsa, took a job with Pearson’s Magazine, and began a love affair with Violet (Tommy) Henry-Anderson, a Scottish golfer who was sixteen years her senior. “Tommy was able to tell me more than I had ever suspected of women’s passionate, romantic involvement with one another,” she wrote in 1986.

In 1926, she and Tommy left New York, sailing through the Panama Canal to San Francisco. Except for a year in Europe, visiting Mills and touring the continent, Gidlow continued to live in the Bay Area for the rest of her life. She and Tommy had been together 13 years when Tommy died in 1935. “We were profoundly sure of our right to be as we were, to love and live in our chosen way, we were happy in it,” Gidlow remembered.

Eventually Gidlow moved to Fairfax, California, then a rural community some fifty miles north of the city. In 1946, she began corresponding with Isabel Grenfell Quallo, a Congolese-born British-American who lived in New York. Gidlow invited her to visit, but she was reluctant, explaining that “a woman who discovers she is a lesbian and is a visible member of a minority has three strikes against her.” She arrived in 1947, only after Gidlow assured her that she lived in an open-minded community.

Gidlow was wrong. Soon the California Senate’s Subcommittee on Un-American Activities called her to testify about her membership in literary and political organizations that allegedly had communist affiliations. Although Gidlow, a philosophical anarchist, ideologically opposed communism, the group’s 1948 report concluded she supported communist front organizations. She also was accused of “living with a colored woman and frequently entertaining Chinese people,” charges she characterized as “damning evidence that I could not be a loyal American.”

In 1954, she and Quallo moved with friends Mary and Roger Somers onto a portion of a ranch she bought near Muir Woods, which she named Druid Heights. It became both their home and a retreat for artists, writers, feminists and free spirits. Quallo returned East to care for family members in 1957, but Gidlow was surrounded for the rest of her life by guests and long-term residents on the property, including Alan Watts, whose book The Way of Zen introduced Eastern philosophy and Zen Buddhism to many European and American readers.

Across her long creative career, Gidlow published 14 books. Her last, Elsa: I Come With My Songs, the first autobiography of a lesbian to appear under its author’s true name, was published by Bootlegger Press in 1986, the year she died. Although she saw herself first and foremost as a poet, Celeste West, her editor, wrote that by then she had added many more beads to her “grey thread” as a “radical feminist of the ‘first wave’” who “fought life-long against class privilege, organized religion, and sexism, while fighting for all varieties of love and beauty.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on October 20, 2022

Recent Comments