By John Lewis–

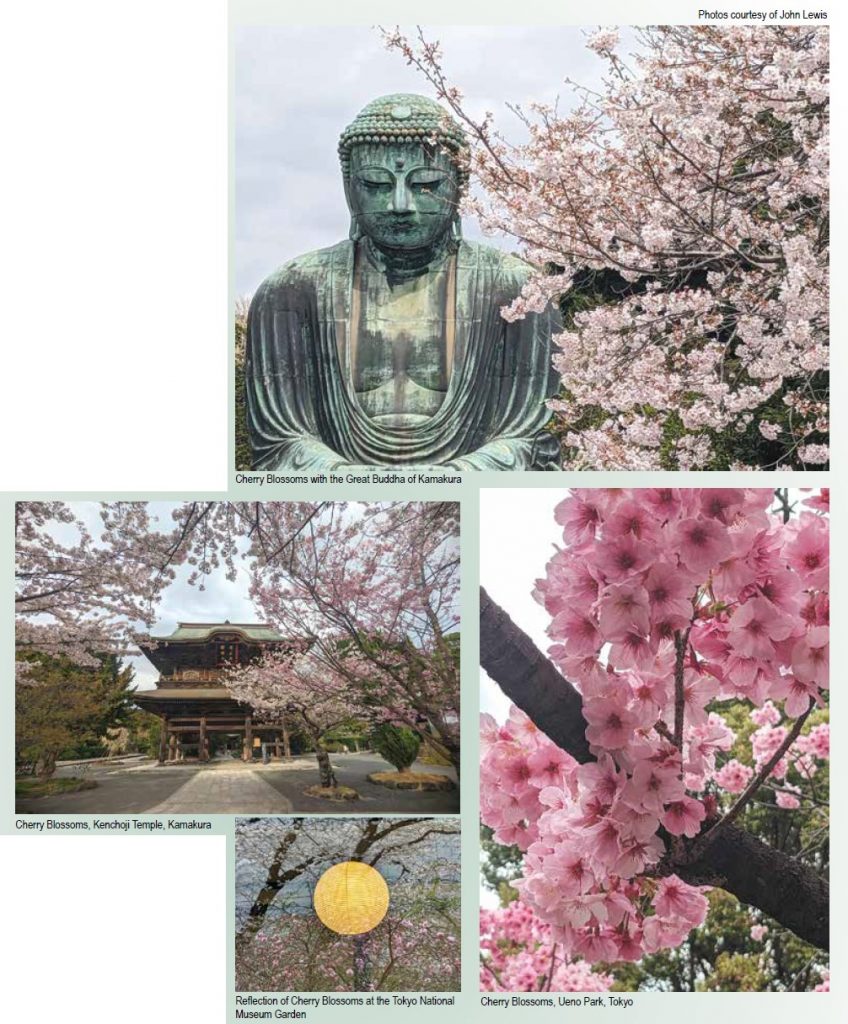

It’s sakura or cherry blossom season in Japan! I’d never been in Japan at this celebratory time of the year, so for weeks I eagerly anticipated seeing splashy displays of bright pink blossoms everywhere. Although there are multiple varieties of cherry trees that boast such showy flowers, I was surprised by something different when the vast majority of the trees started to bloom in my neighborhood—and at temples and shrines, or along paths in public parks and on riverbanks, sometimes by the hundreds and even thousands.

The famous flowers of the dominant species of trees (somei-yoshino) were, in fact, an elegant white in color and sometimes a subtle pink, depending on the light and time of day. And I soon came to learn that the flowers are far more than mere objects of beauty in Japanese culture; they represent something deeper and more nuanced: the ethereal and ephemeral nature of life itself.

To be sure, Japanese and foreigners alike consider the cherry blossoms to be magnificently beautiful. I’ve noticed that Japanese people who often appear reserved in public seem much more outgoing when viewing the flowers. Smiles of delight naturally appear. Taking selfies in front of the flowers goes on everywhere. At first, I thought this a particularly modern phenomenon, which could be considered somewhat superficial (even as I did it myself). However, after I visited an historical exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum and viewed countless paintings of Japanese people admiring the blossoms through the centuries, I realized that selfies were simply the modern manifestation of a storied practice.

But as I experienced the blossoms—especially when seeing them en masse in a blur of color or as a single tree placed “just so” in a traditional Japanese garden—they seemed to possess an other-worldly, transcendent quality beyond selfie-beauty. Planting and placement of cherry blossom trees is very intentional in Japan. I’ve come to see the trees as an indulgence in the sublime that can clear and transform mind and spirit, whether it be through sensory stimulation or quiet calm.

And equally important about cherry blossoms and their meaning in Japanese culture is the fact that they bloom for a relatively short period of time. Traditional Japanese waka poets through the centuries have reflected on the transient quality of the sakura’s beauty. One asked: “O, cherry blossom? The moment that I see you bloom—have you already scattered[?]”

Indeed, when the wind blows, cherry blossom petals descend from tree branches, creating a spring snow shower with drifts of petals scattered on the surrounding ground. Another poet contemplated: “What breeze is it—that is not a cause of regret?”

Beyond these expressions of sorrow at the fleeting nature of the flowers, I believe these ancient poets are actually inviting us not just to see beauty at the moment when the cherry tree is in its full glory but to experience a type of beauty inherent in the omnipresent process of change in life itself that the sakura symbolizes. As the revered Japanese haiku master Bashō, who was also queer, wrote:

“Cherry blossom whirl, leaves fall, and the wind flits them both along the ground. We cannot arrest with our eyes or ears what lies in such things. Were we to gain mastery over them, we would find that the life of each thing had vanished without a trace.”

English translation of waka poetry from http://www.wakapoetry.net/

English translation of Bashō from Robert Hass, The Essential Haiku, Versions of Basho, Buson, & Issa.

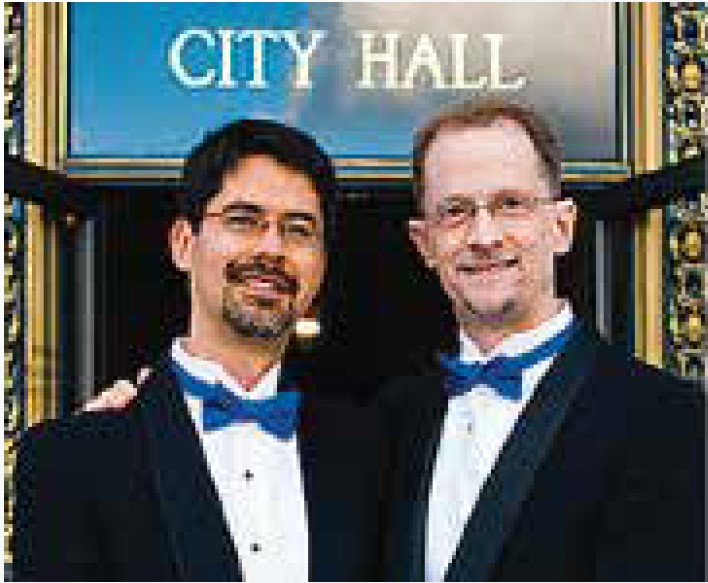

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on April 6, 2023

Recent Comments