By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Although Maḥmūd of Ghazni had nine wives and some 56 children with as many as 32 women, he has been lauded across time for his loving relationship with only one person: Malik Ayāz, his male slave. Their devotion to each other and the affection and the loyalty they shared has been celebrated in Persian epic and lyric poetry, chronicles, and even satire as an example of true, perfect, and constant love for more than ten centuries.

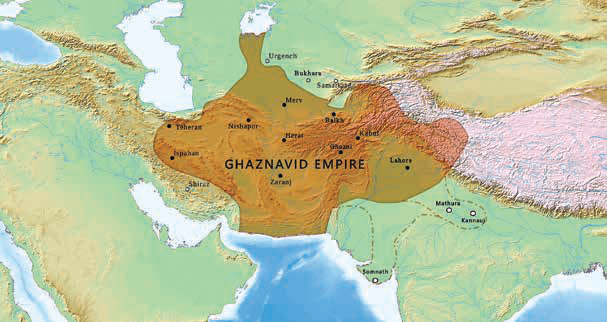

The most famous and celebrated ruler of the powerful Ghaznavid dynasty, Maḥmūd (971–1030 CE) created a vast empire in central Asia that included all of Afghanistan—he was the first man to rule the entire country—as well as most of Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan—and portions of Pakistan and northern India, which he invaded 17 times. His supremacy was so absolute that his subjects called him Sultan (authority). He was the first person in history to have that title.

During Maḥmūd’s lifetime and the years that have followed, however, the great poets and troubadours of Islam have agreed that Ayāz (?–1041 CE) was even more powerful than his master. As the story goes, one day the Sultan asked him if he knew of a mightier and more formidable sovereign anywhere. He replied that he did, explaining that “Maḥmūd is king, but he is ruled by his heart, and Ayāz is the king of his heart.” The strength of Maḥmūd’s love for Ayāz made him “a slave to his slave.”

Although words and meanings change over time, especially in translation, Nizamī-i Arūzī-i’s 12th century account of the couple in the Chahár Maqála (Four Discourses) makes clear that the Sultan was attracted to his slave in every way. “The love borne by Maḥmūd to Ayāz is well-known and famous,” he wrote, because, among his other qualities, he was “mightily endowed with all the arts of pleasing, in which respect, indeed, he had few rivals in his time. Now all these are qualities which excite love and give permanence to friendship.”

Because “Maḥmūd was a pious and God-fearing man, he wrestled much with his love for Ayāz so that he should not diverge … from the Path of the Law and the Way of Honor.” One night, however, “love began to stir within him” as “he looked at the curls of Ayāz and saw … in every ringlet a thousand hearts and under every lock a hundred thousand souls. Thereupon love plucked the reins of self-restraint from the hands of his endurance, and lover-like he drew him to himself.”

Realizing what he was about to do, Maḥmūd decided the best way to calm his passion for his slave was to cut off Ayāz’s curls. “He feared lest the army of his self-control might be unable to withstand the hosts of his locks,” however, so he asked Ayāz to do it himself, which he did immediately. We probably will never know whether or not his actions ended the Sultan’s temptations for all time, but according to Nizamī-i Arūzī-i, “This ready obedience became a fresh cause of love.”

Stories about the deep love and great affection that the two men had for each other are legion. In one, when the Sultan released Ayāz from bondage, he told him, “I give you your freedom and also my empire to rule as I retire from worldly duties.” Ayāz declined this high honor, however. “Giving me the throne,” he replied, “will make me separate from you. All I ever wished was to be with you. How can I be happy with your empire when it is detached from you?”

Were they intimate in every way? The poet Farīd ud-Dīn Aṭṭār, known as Aṭṭār of Nishapur, seemed to think so. Composed in the 12th century, his epic poem Maqāmāt-uṭ-Ṭuyūr (Conference of the Birds) included several tales of Maḥmūd and Ayāz that presented their great love for each other. In “Ayāz’s Sickness,” the Sultan dispatches a courier to his bedside, but arrives before he does:

You could not know

The hidden ways by which we lovers go;

I cannot bear my life without his face,

And every minute I am in this place.

The passing world outside is unaware

Of mysteries Ayāz and Maḥmūd share;

In public I ask after him, although

Behind the veil of secrecy I know

Whatever news my messengers could give;

I hide my secret and in secret live.

Writing two centuries later, the poet and social critic Obayd- Zākāni all but confirmed the Sultan’s true sexuality. One day, he told us, Maḥmūd heard a sermon warning him that whoever makes love to another male, “on the day of judgment will have to carry him across the narrow bridge of Sirat, which leads to heaven.” When Maḥmūd, terrified, began to weep, his jester Talhak told him, “O Sultan, be happy that on that day you will not be left on foot either.”

The days when Maḥmūd could express his great passion for Ayāz openly in Afghanistan are long past. While our queer communities continue to debate which proper pronouns to use and which Pride contingents to include, the LGBT people there are hunted, beaten, jailed, and murdered for even thinking of being themselves. “For homosexuals, there can only be two punishments,” a Taliban judge told the German newspaper Bild before the fall of Kabul, “either stoning, or he must stand behind a wall that will fall down on him.”

The only options LGBT Afghans have are to forever deny who they are, go into hiding, or flee the country. To reach the freedom that Abraham Lincoln called “the last best hope of earth,” they must endure a very arduous, and extremely dangerous journey; not knowing whom to trust, they risk being arrested at every checkpoint out of their homeland. Women, forbidden from traveling without a male relative, have even greater difficulty: they can be arrested simply for trying to cross the border on their own.

Where can they go? Most of the countries that share borders with Afghanistan—Iran, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan—also criminalize same-sex relations. With no realistic prospect of beginning new lives in any of them and with no way to travel somewhere else on their own, their journey to safety is impossible without help from our LGBT communities. We must help.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBT Past

Published on April 20, 2023

Recent Comments