Dr. Bill Lipsky–

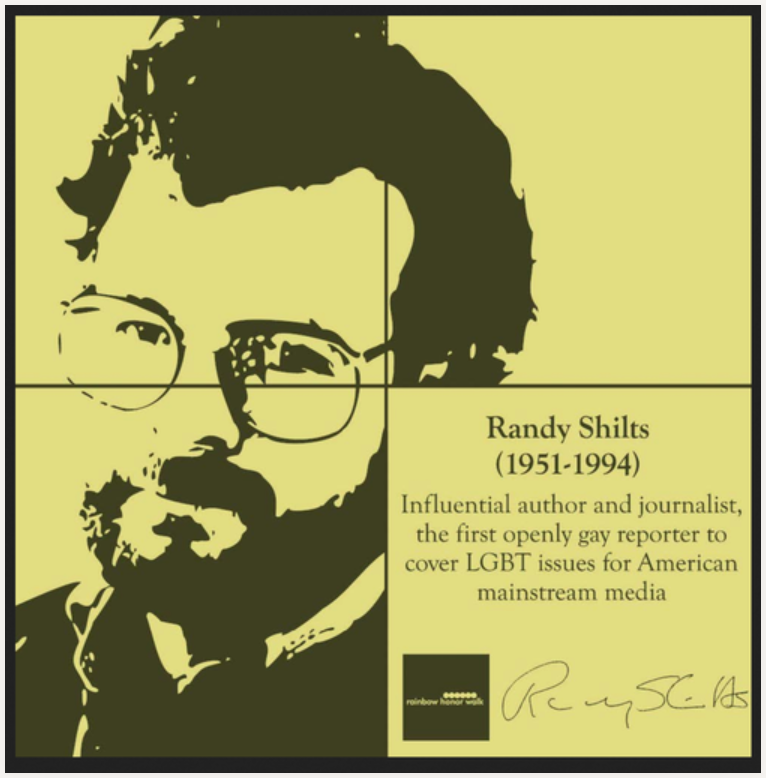

Michael G. Lee has done all of us a great favor. With When the Band Played On, he has written a biography of Randy Shilts, one of the most influential and controversial chroniclers of San Francisco’s gay life in the 1970s and 1980s, that is readable, compelling, and most importantly, insightful. From his difficult childhood to his untimely death, here is Shilts—a complex, enormously talented, hugely ambitious, confident, insecure, arrogant, self-centered, and loving individual—in all his humanity.

Shilts was the first openly gay journalist to cover the gay community full time for a major American newspaper. He started there by reporting about “mundane city matters,” but thanks to both his efforts and his ego, “gay-related features began to noticeably increase.” Over time, however, writing about his world of young, single, white gay men, he often became more controversial than the stories he filed, especially when he lamented “the ‘gayttoization’ of the Castro,” where “the major common denominators for gays today are the three D’s—dope, dick, and dancing.”

“The paradox of Randy Shilts,” Lee writes, “would always be that in critically covering his community, he became an unacknowledged actor in his own stories.” Explaining the issues and the “lifestyle problems” of his generation of gay men, for example, he apparently never realized that he was describing what was important and troubling to him personally, seemingly unaware that many gays were in stable relationships and successful careers, members of multiple communities—religious, professional, social—where real progress had allowed them to be themselves without fearing rejection.

Like all of us, Shilts simply got the story wrong sometimes. When he reviewed the first decade of the gay liberation movement in an article for Blueboy in 1979, Lee writes, “He noted that professional activists still had little to show in actual political victories,” which completely overlooked California’s Consenting Adult Sex Act, passed in 1975 after extensive lobbying efforts that showed the gay community had allies at least in State Assemblyman Willie Brown, State Senator George Moscone, and Governor Jerry Brown.

Lee describes a complicated, driven individual with both noble and self-serving objectives. “Even Randy’s most pointed critiques of gay life contained an unmistakable desire for a kinder, more inclusive gay culture,” he notes. Often ignoring the fact that there were other people in the community besides the men in the bars, the bathhouses, and the bushes, he was genuinely concerned that eventually they “will need more than a washboard stomach, a can of Crisco, a bottle of poppers, and an after-hours bar.”

Shilts’ dual complexity becomes apparent with the stories he chose to tell not only because they were important, but also because they could help him personally or professionally. Early in his career, Lee explains, he attended the Democratic National Convention in New York “with two main objectives: find the definitive gay story at the DNC and showcase his abilities to major news organizations.” Writing And the Band Played On, his vitally important and still controversial history of the AIDS epidemic’s early history, he also “was now focused on the Pulitzer Prize.”

Lee enables us to understand how Shilts often made himself controversial by telling readers what to do about the issues he was reporting. Like a chaperone at a make-out party who is always turning on the lights, he was especially adamant about closing San Francisco’s bathhouses, which he believed “are clearly a major problem with AIDS,” even though he continued to go to them. His taking sides in a divisive argument angered many who believed he was betraying the gay community.

When Shilts moved from journalism to biography and history, he made a crucial decision that some later applauded and others deeply criticized: writing to the drama in the scenarios he constructed. With a great talent for finding and featuring enthralling stories, presented in a vivid, cinematic style—“first came the feeling of being different” read the opening line of Chapter One of The Mayor of Castro Street, his first book—he occasionally made choices that sacrificed balance and accuracy to the momentum of his narrative.

No choice was more controversial that his identifying Gaetan Dugas as “Patient O” of the AIDS epidemic in Band. “He knew that Gaetan wasn’t the only carrier [of the infection],” Lee writes, “but he had the most distinguishing features, an unforgettable name, and a charming disposition,” which made him “a compelling pseudo-villain, whose struggles lent credibility to the fears and frustrations of its beleaguered central characters.” He was “a comparatively late addition, woven into a story for which he wasn’t originally intended, for purposes that would be debated for decades.”

There was no debate, however, that Shilts had made very public an extremely important truth: by doing so little for so long, the unmovable indifference of government, medicine, health care, and society to a major—and growing—public health crisis had enabled the disease to spread unrestrained during the first five years after its appearance, the result of loathing of the gay community, petty squabbles, turf wars, scientific jealousies and rivalries, self-serving interests, and failures of political vision, principle, and equity.

Conduct Unbecoming, his third book, continued his examination of institutional and social attitudes toward members of the LGBT communities. Based upon extensive research that included more than 1000 interviews, it was published in 1993, the year before he died. In it, Shilts documented not only how methodical homophobia led to the mistreatment of gay men and lesbians in the armed services, but also the hypocrisy of an organization that only selectively enforced its ban on homosexuals in uniform. It remains a classic example of investigative journalism.

Our world is different than the one Shilts investigated in his three books. Unlike politicians and other professionals at the time Harvey Milk ran his election campaigns, members of our LGBT communities now can be open about themselves as public office-seekers—or as film stars, newscasters, corporate officers, even professional athletes. AIDS is no longer ignored by public and private institutions. Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender Americans can serve openly in the military services.

Social and political progress may seem to make his work dated and irrelevant to the present, but Lee makes it clear that Shilts did more than write the biography of any individual or present the story of any single public policy. He revealed how bigotry, hypocrisy, and sheer indifference to others become institutionalized; how they deeply damage human lives and increase human suffering. The governments, organizations, and communities may have changed, but his findings, like him or not, are as vital today as when Shilts first shared them.

Shilts was much more complex than any story he reported. Loved by those who knew him well, respected by many who knew him professionally, hated by others who did not know him at all, Shilts is shown by Lee to have been an extraordinarily complicated but very human being: often infuriating, always seeking validation, “doggedly defensive of his work,” controversial, egotistical, self-righteous, and usually right. Here is Shilts in all his dimensions, a fascinating individual who is well worth knowing.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on October 3, 2024

Recent Comments