By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Among the most respected scholars of Renaissance Europe, Marc-Antoine Muret (1526–1585) had just completed a series of hugely popular lectures about the Roman poet Catullus at the College de Boncourt in Paris when he was arrested and imprisoned in the city’s Grand Châtelet, accused of “penchants antiphysiques” with one or more of his young male students, although none of them apparently had complained. Perhaps it was one of his rivals who brought the charges.

Nobody doubted he was close with Daniel Schleicher, a student from Ulm whom he probably met when he taught at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux from 1547 to 1551. When Muret published the first edition of his Juvenilia in 1552, he included among its many elegies, epigrams, epistles, and odes, all written in Latin, a poem where he described him as “a young man surpassing all good men in the blessings of mind, body, and fortune” and “the sweetest son by far.”

Muret also had been devoted to Louis Valesius, whom he proclaimed “an upstanding man” in the book’s final epigram. “You wonder why I’ve put you here at the end, Louis,” he wrote, “even though I embrace you with such great love. The reason is, you are planted deeply in the bottom of my heart. Hence it has come about that you left my heart last.” In addition, his affection for Luc-Menge (Lucius Memmius) Frémiot, who stated that Muret was his “best and dearest teacher,” was already well known.

Despite being recognized as a master scholar and educator, Muret now faced the possibility of being burned at the stake in the public square. He protested his incarceration by taking the only action available to him: he went on a hunger strike. Influential friends finally saved him from both famine and fire, but the man considered to be one of the best Latin prose stylists of his day was forced to flee Paris, disgraced and penniless.

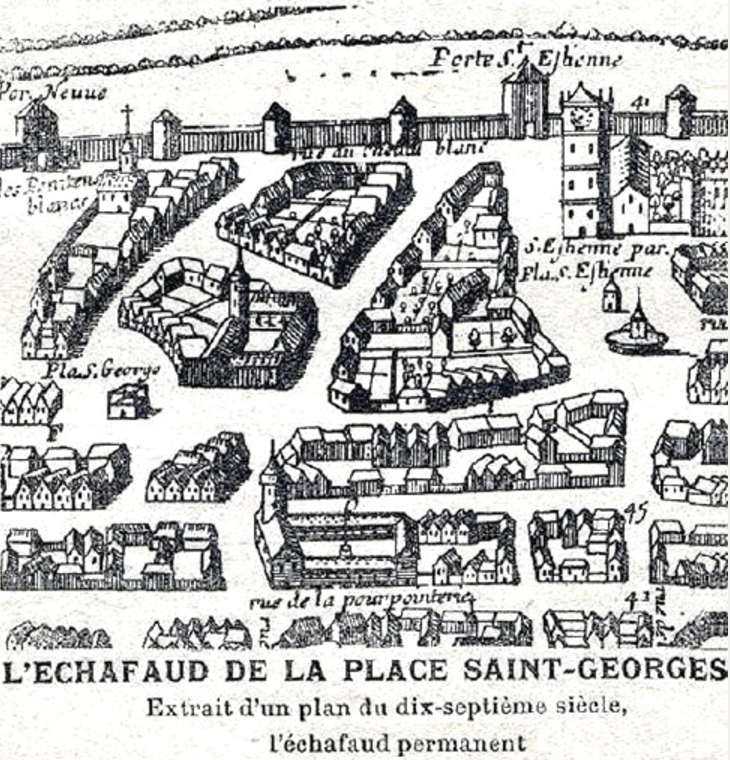

He escaped to Toulouse, but once again was accused of “unnatural vice,” this time with Frémiot specifically. “I want to believe that Muret loved this young boy with an honest love,” French author Gilles Ménage (1613–1692) wrote of him a century later, but “he was accused of loving him with a dishonest love.” About to be arrested, the two men left the city, separately, for more life-affirming opportunities. They then were sentenced to “the penalty of fire” in absentia and burned in effigy in the Place Saint-Georges.

Muret eventually settled in Venice, only to confront new rumors and accusations. According to Joseph Joost Scaliger, a colleague, admirer, and friend (1540–1609), “In Venice they did not want to tolerate him because of his pederasty.” No formal charges were brought against him, “but having tried to sodomize the sons of some of the most eminent noblemen, he fled to Rome,” then to Padua, where he became a private tutor to the heirs of eminent families, until stories about him caused him to lose his students and move again.

Finally, in 1558, he was invited into the service of Ippolito d’Este (1509–1572), Cardinal-Protector of France and a well-known diplomat and patron of the arts. Although Muret had taught classics at various universities since he was 18 and was famous for his translations and commentaries about the works of Cicero, Catullus, Tacitus, Plato, and Aristotle, he was finally secure for the first time in his life. He was either unwilling or unable to create more gossip about himself now, and all allegations of impropriety ceased.

Five years later, Pope Pius IV appointed Muret Professor of Moral Philosophy at the Sapienza University of Rome, founded in 1303, where he taught law and rhetoric for the next 21 years. Celebrated as a learned man of letters and as one of the finest Latin prose stylists of his generation, he modernized instruction with a new system of instruction, known as the “French method of teaching.” He was proclaimed a citizen of Rome in 1571 and ordained a priest of the Catholic Church in 1576.

Perhaps Muret’s greatest and certainly most famous student was statesman and essayist Michel de Montaigne (1553–1592). American transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, a champion of individualism and critical thinking, celebrated him as “the frankest and honestest of all writers,” which he certainly was when he was sharing information about “his romantic friendship with Etienne de La Boétie (1530–1563).” Calling him “my brother and inseparable companion,” theirs was the defining relationship of his life.

Were they intimate in every way? Montaigne described “a friendship so close and so intricately knit, that no movement, impulse, thought of his mind was kept from me.” He never denied his great feelings for La Boétie and the “singular and brotherly friendship which we had entertained for each other.” “If you press me to say why I loved him,” he wrote in his famous essay “On Friendship,” “I can say no more than because he was he, and I was I.”

Montaigne’s Essays first appeared in an English translation by Giovanni (John) Florio in 1603. A prominent linguist, lexicographer, royal language tutor at the Court of James I, and a twice married lover of men, he was one of the most important humanists of his time. Not all of Montaigne’s ideas translated easily from French to English, so Florio created a number of words to make them clearer. Still with us, they included “entrain, conscientious, endear, tarnish, comport, efface, facilitate, amusing, debauching, regret, effort, and emotion.”

La Boétie made his own lasting contribution to humanity with his Discourse on Voluntary Servitude. Written when he was still a college student, it was the first political tract to state the principle of civil disobedience. “To strengthen their power, tyrants make every effort to train their people not only in obedience and servility toward themselves, but also in adoration,” he wrote. Because they fall when the people withdraw their support, “Resolve to serve [them] no more, and you are free.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on November 21, 2024

Recent Comments