By Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis–

The setting was both beautiful and haunting. The jagged snow-capped peaks of the Eastern Sierra gleamed against the clear blue sky. A warm winter sun shone on the barren high desert at the foot of the mountains. For millennia, the native Nüümu (Paiute) and Newe (Shoshone) peoples had lived in harmony on this land they called Payahuunadü. Today, on a large plot of that land, lies the ruins of the notorious Manzanar detention camp, one of ten such camps in which the American government during World War II imprisoned approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans, over 60% of whom were American citizens, for no reason other than their race and ancestry.

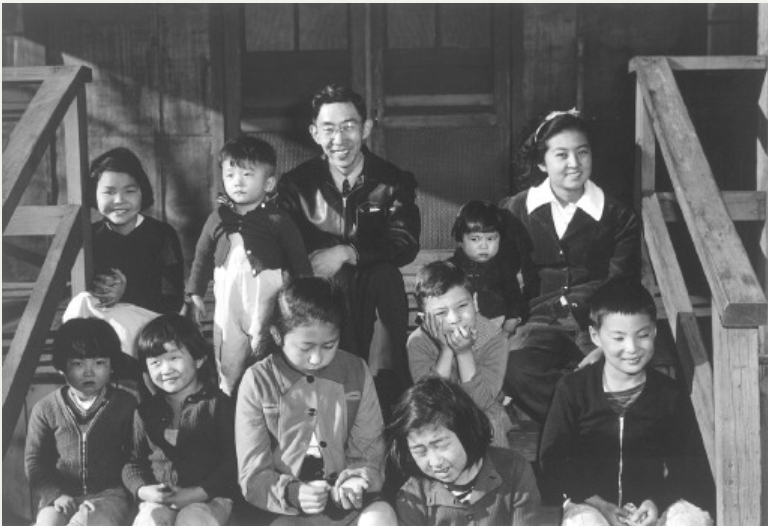

Over the New Year’s holiday, we visited the impressive Manzanar National Historic Site, run by the National Park Service with the help of numerous non-profit organizations and volunteers. The site contains what remains of the actual camp. Housed in the old auditorium building is an extensive museum that recounts unflinchingly what took place during the Japanese American internment, gives voice to those detained there, and preserves artifacts from the camp. In addition, some parts of the camp, including representative barracks, a mess hall, a guard tower, and even the basketball court and baseball field, have been reconstructed. Further restoration is underway.

Just over two months after the Japanese military’s attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast. As the April 6, 1942, edition of Life magazine on display at the museum put it, the expulsion would continue until “every individual of Japanese descent—whether friend or foe—is banished from the strategic areas of the coastal States.” Although national security was the purported purpose of the evacuation, many Japanese Americans had built successful farms and businesses before the war, and wartime hysteria provided those who resented Japanese Americans’ success the opportunity to take away their land, businesses, livelihoods, and homes.

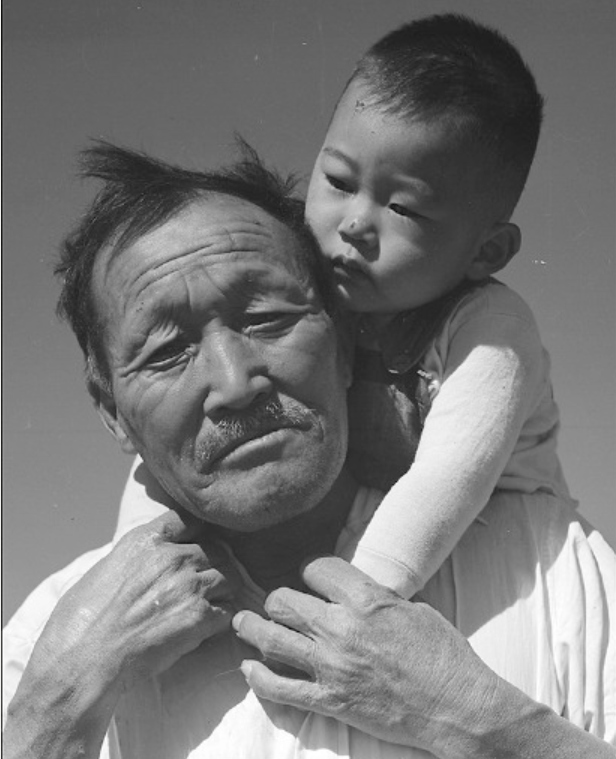

Fumiko Hayashida described how when she was forced to depart her home “[w]e could only carry what we could carry,” her own luggage filled with her young children’s diapers and clothes. Kay Sakai Nakao recalled: “We didn’t even know where we were going, to the Arctic or to the desert or in between. Nobody said anything. We were just leaving, period.”

Upon arrival at the site, Amy Uno Ishii recounted: “There were no trees, nothing green, it was all brown … .” The area was “in the middle of a dust storm. You couldn’t open your mouth because all the dust would come in … . It was a horrible feeling and there was total confusion.” Mary Suzuki Ichino summed up the ordeal of being imprisoned at Manzanar as “like going from a human being to an animal.”

Despite all of this, Life characterized Manzanar as a “scenic spot of lonely loveliness,” while at the same time reminding readers that “Manzanar was a concentration camp, designed eventually to detain at least 10,000 potential enemies of the U.S.” The magazine reported that everything had gone smoothly so far, but it emphasized that “the Army would not shrink from using force to complete evacuation, if other methods failed.” Another purported justification for the camps was to protect Japanese Americans from the hostility of other Americans, causing one prisoner to wonder aloud: “If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

Nothing was more evocative for us on our visit to Manzanar than the ruins of traditional Japanese gardens that detainees had constructed throughout the camp to provide places of peace and comfort under such difficult circumstances. In some ways, the gardens constituted quiet acts of resistance—“radical acts of joy” in the vocabulary of our fellow Bay Times columnist Joanie Juster—with the largest one even named “Pleasure Park” for a period of time.

Large stones and gravel are an integral element of many Japanese gardens, and the gardens’ exposure to decades of harsh weather stripped away all else except their stones and the cement skeletons of the ponds, exposing their elemental existence and pointing to what Zen Buddhism describes as their “suchness.” At the same time, the garden ruins seemed to resemble a type of post-apocalyptic scene, where little remained except tumbleweeds drifting against rocks and dry ponds where once verdant gardens grew and water flowed. Of course, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II left actual nuclear nightmare landscapes.

As we stood reflecting on the remains of the gardens, a provocative, counterintuitive observation by the twentieth-century writer Walker Percy came to mind. During the height of post-World War II, Cold War nuclear anxiety, he wrote: “what people really fear is not that the bomb will fall but that the bomb will not fall.” Percy’s words have been interpreted to speak of people’s deep yearning for release from their feelings of alienation from each other and the frustrations of everyday life.

World War II, which cost over 70 million people their lives, taught us that hyper-nationalism, anti-immigrant hysteria, racism, discrimination, and authoritarianism—although initially attractive to many in times of uncertainty—provide no solution to our feelings of separation from others and the unsatisfactoriness of life itself. Given the rise of nationalism today in many parts of the world, including the U.S. with the return of Donald Trump to the White House, Manzanar stands as an important historical reminder close to home of what can go wrong when such forces dominate.

As 2025 unfolds, we will derive strength from the fortitude and resilience of Japanese Americans confined at Manzanar, as well as from the actions of all those who stood up against this deprivation of human rights. And we will remember the stillness we experienced as we stood in the warm sun amidst the garden stones that remain where they were placed by Japanese Americans over 80 years ago, likely never imagining they would continue to provide comfort generations later.

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

6/26 and Beyond

Published on January 16, 2025

Recent Comments