By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

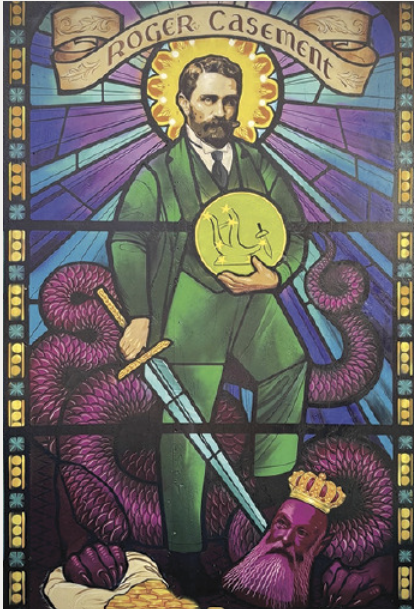

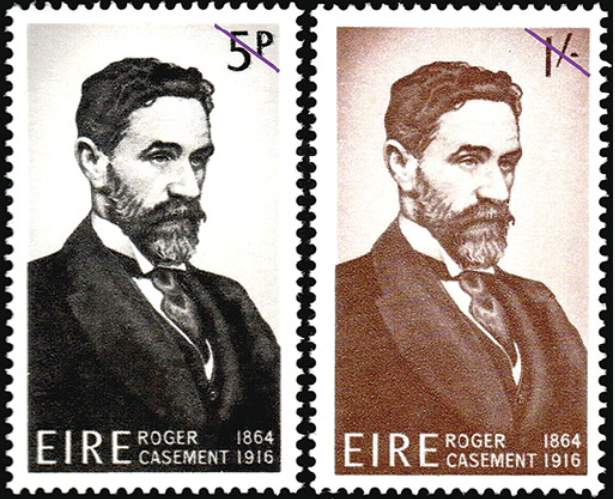

“Imagine a tall, handsome man, of fine bearing; thin, mere muscle and bone, a sun-tanned face, blue eyes, and black curly hair. A pure Irishman he is, with a captivating voice and singular charm of manner. A man of distinction and great refinement, high-minded and courteous, impulsive and poetical. Quixotic, perhaps some would say, and with a certain truth, for few men have shown themselves so regardless of personal advancement.” Imagine the great and good man who was Roger Casement ((1864–1916).

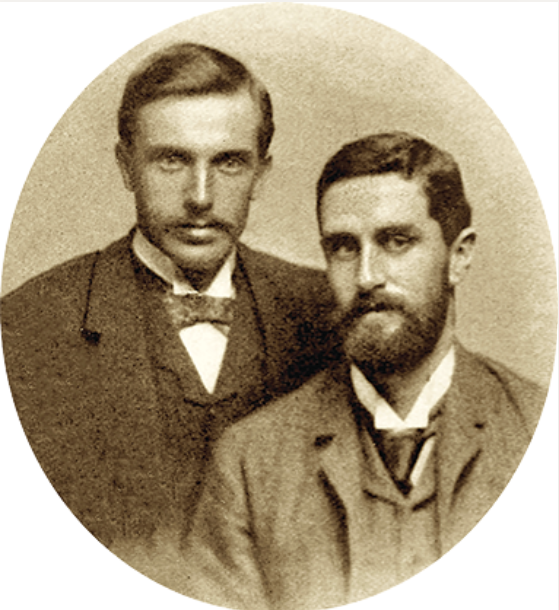

Herbert Ward’s description of his dear friend Roddie, as he called him, captured the special appeal, the force of personality, and the shear attractiveness of the individual often named the “father of twentieth-century human rights investigations.” “No man walks this earth at the moment who is more absolutely good and honest and noble-minded,” he wrote to E. D. Morel, who supported Casement’s work to abolish the systematic inhumanity willingly being imposed by Europeans upon the people of Africa.

In 1884, barely 20 years old, Casement became an employee of the African International Association, founded by Leopold II of Belgium to explore and “to civilize the Congo,” which was neither unexplored nor uncivilized. The organization’s stated goal “to free its inhabitants from slavery, paganism, and other barbarities” was simply a hypocritical fig leaf used to hide a naked economic truth: the land and its people were being ruthlessly exploited for the enrichment of a king who claimed he personally owned both.

It was rubber that made the Congo the most profitable colony in Africa. To gather and transport it, Leopold condoned a reign of terror that controlled and abused its people through deprivation, starvation, and murder; many workers who failed to meet their assigned quotas were punished by having a hand or arm chopped off. Millions died. Dear Daisy may have looked sweet upon the seat of a bicycle built for two, but she rode on tires soaked with the blood of once free Africans.

During Casement’s many years in Africa, he became thoroughly disillusioned with Europe’s supposed “civilizing” colonialism. When the British government appointed him its consul at Boma in the Congo in 1903, he began investigating the extreme human rights abuses there. The result: a 50,000-word report that included eyewitness accounts exposing “the enslavement, mutilation, and torture of natives on the rubber plantations,” a damning exposé that made Casement famous as “the world’s first human rights investigator.”

In recognition of his service, Casement received the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George in 1905, but his time in Africa not only changed conditions there; it also changed his view of colonialism and his view of himself. “I had accepted Imperialism,” he wrote in 1906, because he believed “it was the best for everyone under the sun.” The Boer War (1899–1902), however, “gave me qualms at the end.” Finally, “up in those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold, I found also myself, the incorrigible Irishman.”

Casement was rapidly becoming an ardent Irish nationalist. Meanwhile, the British appointed him to several consular posts in Brazil before making him consul-general in Rio de Janeiro in 1909. There, he took up an investigation of human rights abuses by the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC), an organization whose board of directors and major stockholders were British, but whose local administrators were destroying the indigenous people of the Putumayo to profit from the world’s demand for rubber.

Traveling at great personal risk far into the Amazon, Casement observed mistreatment that, he reported, “far exceeds in depravity and demoralization the Congo regime at its worst.” His findings outraged public opinion, causing the PAC eventually to collapse, although its manages were never prosecuted for their crimes against humanity. In 1911, he was knighted for his great work. Two years later, exhausted by almost 30 years’ service in Africa and South America, he retired from the consular service.

Now thoroughly disillusioned with the realities of empire, he devoted his attention to Ireland, advocating first for Irish Home Rule, then for Irish Independence. When the Great War between Britain and Germany began in 1914, he began negotiating with Berlin for assistance. Two years later, the Kaiser’s government finally agreed to send some arms, but the British intercepted them before they arrived. Returning at the same time to Ireland on a German U-boat, Casement was captured, moved to London, imprisoned in the Tower, tried for treason, convicted, and sentenced to death.

As “a humanitarian figure of astonishing international reputation,” appeals for clemency arrived from all over the world. In Great Britain, Arthur Conan Doyle circulated a petition signed by a who’s who of eminent, loyal subjects of the Crown: novelist and playwright Arnold Bennett; G. K Chesterton, creator of the Father Brown detective stories; John Galsworthy, author of The Forsyte Saga; and many others, including the editors of such important publications as The Nation, The Contemporary Review, and The Manchester Guardian.

Perhaps his most loyal and ardent defender was Irish suffragette, feminist, and human rights advocate Eva Gore-Booth, then living in London with her life partner Esther Roper, who was actually granted an audience with King George V to plead for Casement’s life. His Majesty simply claimed he was powerless to act, although his views can well be imagined; during the 1931 scandal that engulfed William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp, he reportedly said, “I thought men like that shot themselves.”

Support for Casement in the United States was widespread and diverse. Author Mark Twain (née Samuel Clemens) called for leniency; he had been so deeply moved by Casement’s 1904 report that he wrote King Leopold’s Soliloquy, published the next year, an undisguised condemnation of the imperialist’s extremely cruel and brutal administration in the Congo. Publisher William Randolph Hearst used his extensive newspaper empire to lobby the U. S. Senate to pass a resolution calling for Casement’s reprieve from death.

The African American community was especially sympathetic. The Negro Fellowship League, founded in 1910 by human rights activist Ida B. Wells and her husband Ferdinand Barnett, sent an appeal for clemency directly to George V. “Because of [his] great service to humanity, as well as to the Congo natives,” it said, “we feel impelled to beg for mercy on his behalf. There are so few heroic souls in the world who dare to lift their voices in defense of the oppressed who are born with black skins.”

The Senate passed Hearst’s resolution 46–19 and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, on behalf of its 280,000 members, sent a telegram calling for clemency, but the White House opposed it. Even after being told that “a personal request from the president will save his life,” Woodrow Wilson refused to act; the Senate’s resolution was not delivered officially to the British government until an hour after Casement’s execution. Not that it would have mattered. None of the appeals made a difference.

From the beginning, the British government had been determined not only to convict Casement, but also to destroy him completely. Shortly after his arrest, investigators seized his diaries, which included both descriptions of his work on two continents and shockingly detailed notes about his sexual relationships with men. Although the information was not used as evidence at his trial, the government began sharing it with many individuals, including the American ambassador and other influential leaders, to deliberately stain his character and undermine the campaign for a reprieve

He was stripped of his knighthood, which has never been restored, and on the day he was sentenced to death, the British authorities transported him to London’s Pentonville Prison, where Oscar Wilde served part of his sentence for “gross indecency” some twenty years before. He might have used his homosexuality to plead that he was “not guilty by reason of insanity,” possibly saving his life, but he refused. After his death by hanging on August 3, 1916, his executioner called him “the bravest man it ever fell to my unhappy lot to execute.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBTQ Past

Published on August 28, 2025

Recent Comments