By Bill Lipsky—

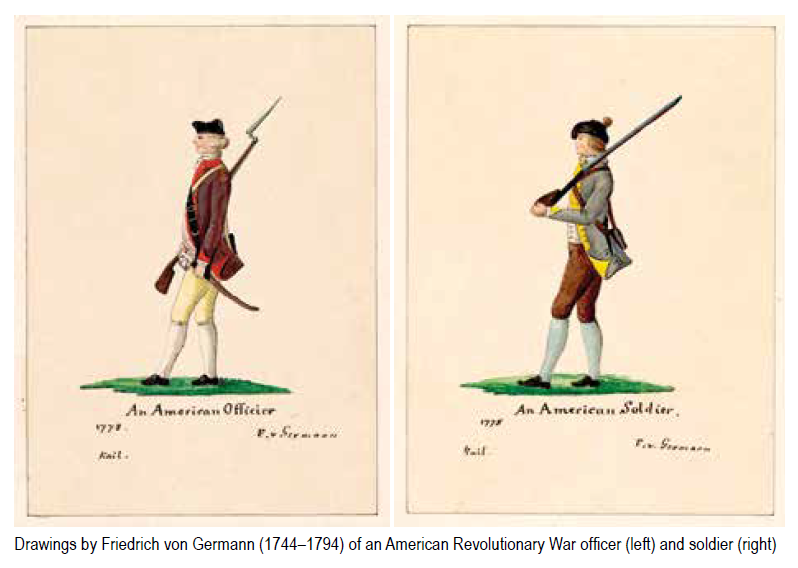

On March 10, 1778, Gotthold Frederick Enslin became the first soldier to be tried, convicted, and expelled from the Continental Army for “Infamous Crimes” with another serviceman. Commander in Chief George Washington personally approved the court-martial decision. Whether Washington signed the discharge order because Enslin had been found guilty of intimate relations with a private, or because Enslin had been discovered socializing with someone below his rank, which was equally forbidden and scandalous, or because Enslin had lied about the matter to a superior officer, Washington secured the lieutenant’s place in history.

Almost nothing is known of Enslin’s life before he joined the army. He had traveled to the newly proclaimed United States of America on the Union, a recently built ship of “250 tons burthen” that arrived at Philadelphia on September 30, 1774. The ship had been built in Philadelphia and then registered for passengers barely six months earlier, on April 2, after a journey that originated in Rotterdam with calls at Portsmouth and Cowes. Enslin joined the fight for American Independence as a lieutenant three years later.

On February 27, 1778, his moral integrity became the concern of “a Brigade Court Martial” when “Ensign [Anthony] Maxwell of Colonel [William] Malcom’s Regiment [was] tried for propagating a scandalous report prejudicial to the character of Lieutenant Enslin.” Fortunately for Maxwell, but not for him, “the Court after maturely deliberating upon the Evidence produced could not find that Ensign Maxwell had published any report prejudicial to the Character of Lieutenant Enslin further than the strict line of his duty required and do therefore acquit him of the Charge.”

The summary of findings did not include information about what Maxwell had reported to his superiors about Enslin. That became all too clear at another Court Martial eleven days later, when he was “tried for attempting to commit sodomy with John Monhort, a soldier [and] secondly, for perjury in swearing to false accounts.” Found “guilty of the charges exhibited against him, being breaches of 5th Article 18th Section of the Articles of War,” his judges “sentence[d] him to be dismiss’d [from] the service with Infamy.”

No transcript of the proceedings, no statement of evidence, and no list of witnesses survive. Only Washington’s review of the court’s decision and the punishment he ordered survives. “His Excellency the Commander in Chief approves the sentence and with Abhorrence & Detestation of such Infamous Crimes orders Lieutenant Enslin to be drummed out of Camp tomorrow morning by all the Drummers and Fifers in the Army never to return; the Drummers and Fifers to attend on the Grand Parade at Guard mounting for that Purpose.”

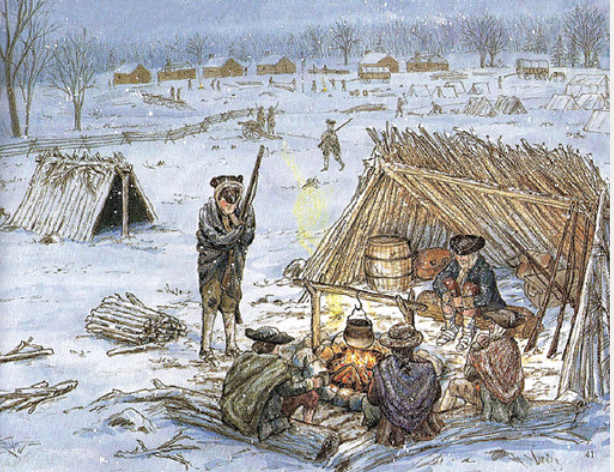

Enslin was literally drummed out of the service on March 15, 1778. His colleague, Lieutenant James McMichael, later described Enslin’s disgrace in a diary entry: “He was first drum’d from right to left of the parade, thence to the left wing of the army; from that to the centre, and lastly transported over the Schuylkill with orders never to be seen in Camp in the future. This shocking scene was performed by all the drums and fifes in the army—the coat of the delinquent was turned wrong side out.”

As harsh and unenlightened as Enslin’s punishment may seem now, Washington had actually showed great leniency and restraint. At the time, Pennsylvania law required that anyone convicted of sodomy “shall suffer imprisonment during life and be whipped at the discretion of the magistrates, once every three months during the first year after conviction. If he be a married man, he shall also suffer castration, and the injured wife shall have a divorce if required.” Instead, the General allowed him, although Enslin was greatly humiliated, simply to walk away.

Enslin left Valley Forge just sixteen days after Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben arrived there. Before that he had been busy reforming and modernizing the army of Frederick the Great of Prussia, but was forced into exile for allegedly becoming too close to some of the young men under his command. Although Benjamin Franklin, Commissioner for the United States to France, knew all the stories about him, he still recommended him for the position of Inspector General of the Continental Army, which he accepted.

During the bleakest of times for the American Revolution, Steuben presented himself at Valley Forge with his own servants, a French cook, an aide-de-camp, a miniature greyhound, and his 17-year-old personal secretary and companion, Pierre-Étienne du Ponceau, his presumed lover, who shared his accommodations. Serving directly under Washington, he shaped the disarrayed Continentals into an organized, disciplined, and effective fighting force that was able to win the war. The army continued to follow the principles of the training program he implemented for decades.

Steuben barely spoke English, but he could speak excellent French, so Washington assigned his own secretary and one of his aides-de-camp to assist him. Who were they? They were his dear friends, Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens, both officers, who lived together at Valley Forge. Theirs was an impassioned, emotionally intimate, and enormously loving relationship. Although both men eventually married, the deeply expressive language contained in the letters they wrote to each other, stated one biographer, “raises questions concerning homosexuality” that “cannot be categorically answered.”

While at Valley Forge, Steuben entered into his own “extraordinary intense emotional relationships” with William North and Benjamin Walker, two military officers, then in their 20s. After the war, he legally adopted them both. When he died, they inherited the bulk of his estate. (North, who married, named two of his six children after his mentor.) John Mulligan, who also considered himself one of “Steuben’s sons” and who was with him during his later years, received his books, maps, and $2,500 in cash, then a considerable sum.

Almost nothing is known about Enslin’s life after he crossed the Schuylkill. He may have moved to Boston, where he—or another man with the same name—married Elizabeth Geye on July 24, 1784. More is known about Monhort, however. He was born in New York around 1760 and enlisted as a private in Malcom’s Regiment in 1777. Promoted to the rank of corporal in May 1779, he remained with the army until the spring of 1780. Never tried for his intimacy with Enslin, he died in 1835.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBTQ Past

Published on January 15, 2026

Recent Comments