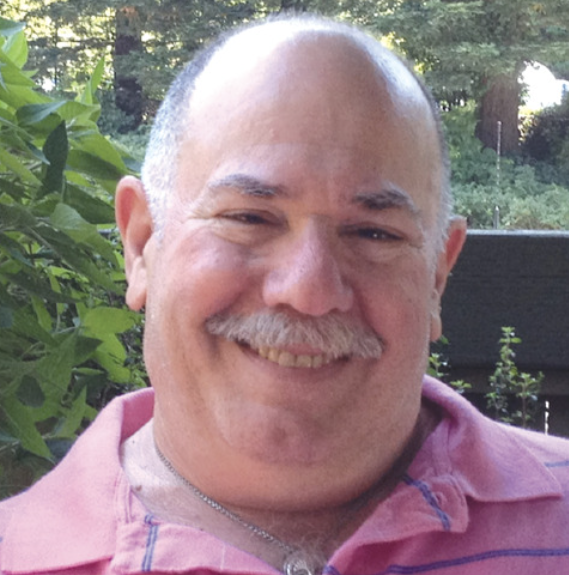

By Dr. Bill Lipsky—

The biblical princess Salome is possibly the most notorious dancer in history. Her “Dance of the Seven Veils” has mesmerized us for the last 2000 years, but never was her wickedness more entrancing than during the divinely decadent years around the turn of the 20th century. Beginning with Oscar Wilde’s symbolist play about her in 1892, banned in England because the law forbade biblical figures being portrayed on stage, Salomania became an authentic cultural phenomenon that swept across theater, music, art, merchandising, fashion, and film for the next 30 years.

Except for Salome herself, however, no one brought more attention to her infamous performance than Maud Allan. Born Ulla Maude Durrant in Toronto, Canada, on August 27, 1873, she and her family moved to San Francisco soon after, and she grew up here. The children attended Lincoln High School before Maude transferred to Cogswell Technical School in the Mission and brother Theo went off to a private boarding academy, then enrolled at Cooper Medical College on Sacramento Street, which became part of Stanford University’s School of Medicine in 1908.

A talented youngster, Maude also took piano lessons from Eugene Bonelli, founder and director of the San Francisco Grand Academy of Music at Franklin Street and Golden Gate Avenue. The maestro was so impressed with her that he recommended she go to Europe to complete her musical studies. She did not consider a career as a dancer until she met famed pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni at the Meister-Schule in Weimar, who persuaded her to pursue a career where “her body was her instrument.”

Maude was in Europe less than three months when news reached her that her brother Theo had been arrested as “The Demon of the Belfry” for the murder of two women at San Francisco’s Emmanuel Baptist Church, then on Bartlett Street between 22nd and 23rd streets, where he was assistant superintendent of the Sunday School. Coverage in the press was so sensational, so widespread that the court interviewed more than 3,600 potential jurors before 12 could be chosen for his trial.

Found guilty on November 1, 1895, and sentenced to death, Theo was hanged for murder at San Quentin on January 7, 1898. “I bear no animosity toward those who have persecuted me,” he said in his last statement, “not even the press of San Francisco, which hounded me to the grave.” Many now believed the church building was a haunted, evil place and wanted it gone, but it was not torn down until 1915. Today the site lies under City College’s Mission Center.

Maude was convinced of her brother’s innocence, but, at his insistence, remained in Europe. To distance herself professionally from his tragedy, however, she called herself Maud Allan when she first performed as a dancer in Vienna on November 24, 1903, presenting what she would later call her “musically impressionistic mood settings” for Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, Chopin’s Funeral March, and Rubinstein’s Valse Caprice. Critics were not impressed, describing her as someone who did not contribute much to the modern dance movement, but audiences adored her.

Allan premiered The Vision of Salome, her most successful, famous, and best remembered work in Vienna late in 1906. For the next two years, she toured Europe, always to rapturous jubilation. Audiences were simply overwhelmed by the sexual energy of her performance. Whether they were also delighted, outraged, shocked, or repulsed by her erotic costume and the realistic wax head of John the Baptist, Salome’s victim, which she used as a prop in a “decidedly gruesome” way, she triumphed wherever she appeared.

She conquered London in 1908. What began as a two-week engagement became a cultural phenomenon that lasted for 18 months. She presented her Salome some 250 times, including at matinees and special performances. The August 8, 1908, issue of The Sun (Baltimore) included: “[T]his young woman was the sensation of Paris … and remains the wonder of London.” Gertrude Hoffman, one of the many, many rivals she inspired to follow her in the role, publicly stated that she was “the greatest of all ‘Salomes.’”

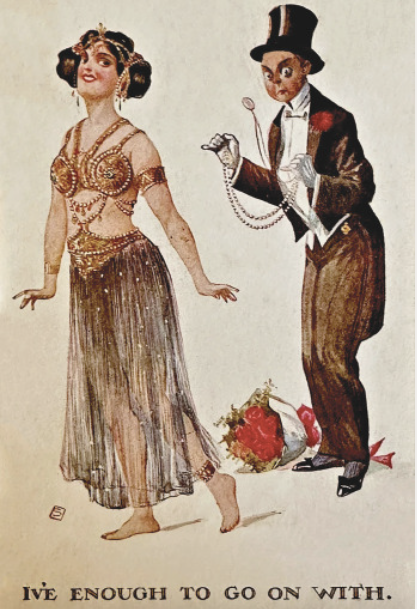

The newspaper disapproved of Salomania, however. “Seldom has a fad, and especially so questionable a one, spread with such amazing rapidity,” it editorialized. “Actresses and singers, as well as dancers, who made their living in other kinds of work have found out that if they want to stay in the game successfully, they must learn how to do the ‘Salome’ act.” Even so, it admitted, the great opera stars “Melba, Tettrazina, [and] every other musical and dramatic sensation are nothing compared to the present vogue of Miss Allan in this dance.”

Allan and her imitators simply made the guardians of other people’s morality nervous. As Adam Alston wrote, many warned that “the proliferation of scantily clad Salomes would pollute the contained, corseted bodies of respectable women and corrupt the minds of men.” Others harrumphed that “the vulgar dance would encourage the spread of immoral thoughts and behavior among immigrants, urban youth, and those vulnerable to cheap amusement.” Still others were concerned that their example might lead a to a loss of male authority, suffrage, and result in the “emancipation of women.”

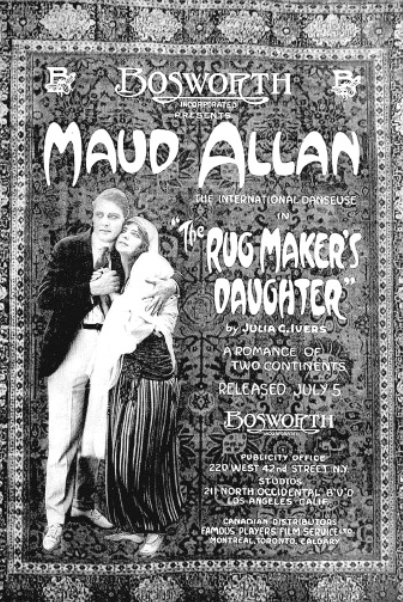

At the height of her fame, Allan returned to the United States in 1915. She visited her parents in Los Angeles, where they had moved after her brother’s ordeal. That summer she made her only motion picture, The Rug Maker’s Daughter, which featured excerpts from three of her dances. Billed as “The International Danseuse,” she co-starred with Forrest Stanley and Jane Darwell, who won an Academy Award in 1941 for her role in The Grapes of Wrath and won our hearts as the Bird Woman in 1964’s Mary Poppins.

Allan toured North America for two years, then departed for London in 1918, where she was to appear in two private performances of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, translated into English by Alfred Douglas. Soon she was involved in one of the most sensational trials of her time, after suing Noel Pemberton-Billing, an extremist Member of Parliament, for publishing an article accusing her of being “a member of a ‘cult’ of women who loved women” and of having an intimate relationship with Margot Asquith, wife of the former Prime Minister.

Whatever the truth of their relationship, Margot Asquith paid for Allan’s apartment overlooking tony Regent’s Park from 1910 until 1928. Verna Aldrich, once Allan’s secretary and then her lover, made the payment for the next ten years. A bitter dispute finally ended their involvement, but Allan continued to live there until the Germans bombed the building during World War II. She eventually returned to Los Angeles, where she died on October 7, 1956, all but forgotten by the world she had so startled.

Salomania, like all enthusiasms, eventually faded, although Salome herself continued to fascinate the public. Norma Desmond, entranced by her story, wrote a screenplay about her in Sunset Boulevard, Billy Wilder’s 1950 film, and she appeared on screen two years later, portrayed by Rita Hayworth. A few years after that she was seen once again, at least in San Francisco, when José Sarria and The Black Cat Opera & Ballet Association rethought her most famous performance for a Sunday afternoon drag parody, presenting the “Dance of the Seven Trick Towels.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on February 12, 2026

Recent Comments