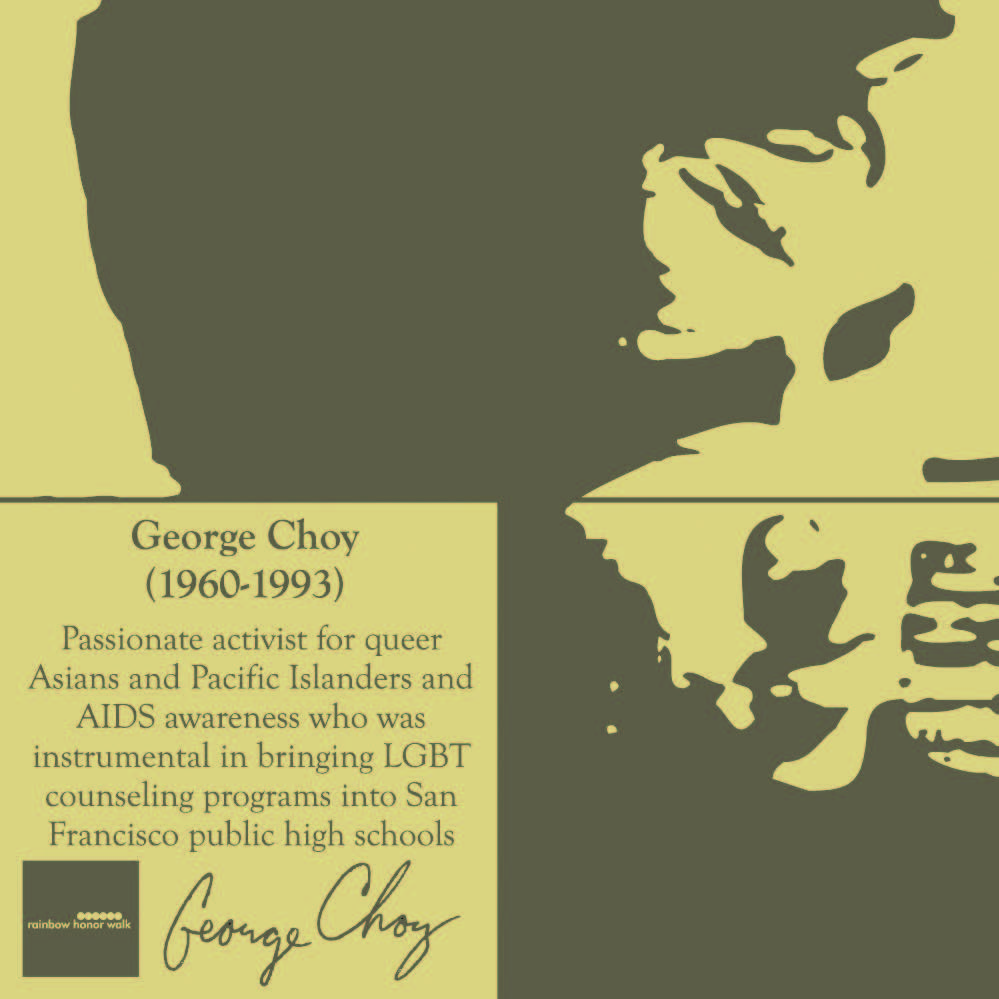

George Choy was a passionate advocate of civil and human rights for members of the LGBTQ communities of San Francisco and around the world. Driven by the belief that we are “part of the family, too,” he became “a constant supportive presence who delivered with action, an activist impatient with injustice, but who nevertheless possessed the rare gift of forgiving.”

George Choy was a passionate advocate of civil and human rights for members of the LGBTQ communities of San Francisco and around the world. Driven by the belief that we are “part of the family, too,” he became “a constant supportive presence who delivered with action, an activist impatient with injustice, but who nevertheless possessed the rare gift of forgiving.”

Being born on February 6, 1960, Choy liked to say that he was an Acqueerian. He came out to himself during the summer after he graduated from San Francisco’s Mission High School, just before leaving to attend San Jose State University. Instead of feeling guilty, “instead of lying to myself and others,” he told himself to “be happy and love who[m] you want.”

His self-awareness, insight, and perception were transformative. “I was free,” he wrote later. “I no longer hid from my straight schoolmates about my sexuality.” He told his two closest friends, hoping they would “support me.” Both did. He was best man at their weddings, and they remained lifelong confidents.

Choy saw the need for activism early on. He grew up in Chinatown, across the street from the International Hotel. Once the heart of San Francisco’s Philippine community, the Filipino seniors who lived there were forcibly evicted for an “urban renewal” project during the 1970s. Their protests to save their homes and preserve their community—which at one time included ten blocks of low-cost housing, stores, restaurants, markets, and other businesses that supported a neighborhood of some 10,000 people–left an indelible impression on him.

Believing that we all belong to a larger world than our ethnic, religious, or social identifications create for us, Choy wanted to make connections across artificial barriers to show our common humanity. This goal propelled his activism. Especially committed to achieving full civil and human rights for LGBTQ Asians, he became an early and active member of San Francisco’s Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA).

Believing that we all belong to a larger world than our ethnic, religious, or social identifications create for us, Choy wanted to make connections across artificial barriers to show our common humanity. This goal propelled his activism. Especially committed to achieving full civil and human rights for LGBTQ Asians, he became an early and active member of San Francisco’s Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA).

Choy was also vocal in support of queer youth—an often neglected minority within a minority. In the Spring of 1990, he was asked to lead GAPA’s effort to pass Project 10, a measure to provide much needed counseling services for San Francisco’s LGBTQ public school students. Although he believed that “living in San Francisco helped a lot of straight people deal with gays,” he also knew that there were still “those who experi-enced gay-related violence,” including some “attacked by family members because of their sexuality.”

The proposal faced numerous hurdles, with opponents claiming that it was either unnecessary or inappropriate, or not fundable. Choy, however, immediately recognized its importance for all students, especially for Gay Asians. “We have to be there,” he said, “to make sure they know that there are Gay Asians.” “They” included not only members of the school board and the mostly white gay activists who supported the proposal, but it also included Asian Christian funda-mentalists, who had come out in full force against the measure, arguing simply that the service was not needed because there were “no gay Asians.”

During the critical meeting at which the Board was to vote on the proposal, Choy made an impassioned plea for it to pass. He argued that Gay Asians were “not to be taken for granted,” but to be “loved, saved, and protected.” In May, 1990, the Board of Education decided unanimously to implement Project 10 the following September. “This program,” said Kevin Gogin, the first counselor hired, “will send a message that all people are important, no matter who they are.”

During the critical meeting at which the Board was to vote on the proposal, Choy made an impassioned plea for it to pass. He argued that Gay Asians were “not to be taken for granted,” but to be “loved, saved, and protected.” In May, 1990, the Board of Education decided unanimously to implement Project 10 the following September. “This program,” said Kevin Gogin, the first counselor hired, “will send a message that all people are important, no matter who they are.”

Choy’s efforts to realize civil rights for gay Asians went far beyond San Francisco. In 1991, GAPA supported a lawsuit against a public youth act-ivity center in Tokyo, which denied the use of its facilities to OCCUR, a local LGBTQ organization. When mem-bers of OCCUR visited the City to gain support for their anti-discrimination case against the Tokyo government, he became their point person. He organized press confer-ences, held meetings, and got local political figures involved. Then he traveled to Japan to speak about human rights for gays to large audiences in Tokyo and Osaka, one of San Francisco’s sister cities.

At the same time, Choy worked as the Community HIV Project Liaison for GAPA. He next became the outreach coordinator for the GAPA Community Health Project, which provided direct support services to gay Asians and Pacific Islanders that included prevention, education, early inter-vention, HIV case management, emotional and practical support, and direct care. He also was an active and ardent member of ACT UP. More than anything else, he showed what a single individual can do for the benefit of us all.

Not long before he died of AIDS on September 10, 1993, Choy spoke of what he had learned since that summer after high school. “Deep inside each of us,” he told his audience, “burns a special flame…which other people misunderstand…But we, as gay and lesbian people, understand…that we have a special capacity to love one another. We understand that this love is real and valid. We understand that this special flame will light the way for us…Continue to fan the flame, strong, proud, and just.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments