The groundbreaking, breathtaking contributions that designing LGBT men and women made to the world’s skyline deserve a place on any list of the great monuments. Whether or not their work included a “queer sensibility,” they often created architectural styles that were popular for decades.

The groundbreaking, breathtaking contributions that designing LGBT men and women made to the world’s skyline deserve a place on any list of the great monuments. Whether or not their work included a “queer sensibility,” they often created architectural styles that were popular for decades.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Pierre Fontaine (1762–1853) and Charles Percier (1764–1838) were the principle exponents and greatest champions of the neo-classical Directoire or Empire style, which rejected the old monarchist traditions for a new, fresh expression of enlightenment.

Napoleon Bonaparte liked their work. In 1801 he named Fontaine his personal architect, a position that Fontaine insisted on sharing with Percier. Together the men refurbished the palaces at Fontainebleu, Strasbourg, and Versailles; renovated the Louvre; and built the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. Both became officers of la Légion d’honneur for their creative contributions to France.

Percier and Fontaine were both business and life partners. They met while students in Rome, where they swore “a pact of friendship founded on respect and confidence,” promising never to marry. When Percier died in 1838, Fontaine wrote to a colleague, “I have lost half of myself.” He designed Percier’s mausoleum in Père Lachaise Cemetery and left instructions that, after his own passing, his body be interred with that of his life’s companion, and it was.

Oscar Wilde found the American urban landscape deplorable. “The fault,” he said during his visit to the United States in 1882, “is in an entire want of any definite concept of what style is suitable for your cities.” For Ralph Adams Cram (1863–1942), the elegance of medieval public architecture was the answer and he became the preeminent advocate of the Gothic Revival Style in the United States.

Cram, who wanted buildings to communicate a spiritual value to balance the secularism of modern civilization, became the most celebrated designer of churches and universities in America. Few people suspected or appreciated the irony that it was a gay man who created the new campus of the U.S. Military Academy in 1902; the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York; the Princeton University Chapel; and the Doheny Library at the University of Southern California.

Unlike Cram, Emily Williams (1869–1942) worked for greater and more functional simplicity. With a style vastly different than his—and at a time when very few women were able to join the profession—she became a pioneering architect in Northern California.

Williams was a teacher when she met Lillian Palmer around 1898. Palmer encouraged Williams to follow her creative heart. In 1901, the two women moved to San Francisco, where Williams studied drafting at the California High School of Mechanical Arts. “Miss Williams’ houses,” noted the San Jose Mercury and Herald, in its November 11, 1906, issue, “are not only beautiful and artistic, but convenient, livable and planned to save steps and with places to put things.”

In 1908, the couple traveled to Vienna, where Emily studied architecture and Lillian metal work. When they returned, Palmer opened a successful metal art studio, but Williams struggled to receive commissions. Eventually she found support among prominent women, building a home for Anna Lukens, an early female physician, in Pacific Grove, and the Gertrude Austin House at 2728 Union Street in San Francisco. Her home for Arthur M. Free, 66 South Fourteenth Street, San Francisco, and the house she built for herself and Palmer at 1037 Broadway are now listed buildings.

Philip Johnson (1906–2005) became one of architecture’s most influential masters. He was 36 years old before he designed his first building: his residence, the now famous Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, done with an unobvious choice of materials for a gay man in 1949. Always an apostle of the modern, he first championed the sleek towers of the International Style, then turned to a more provocative elegance that combined Minimalism with Pop Art for something entirely new, often called Postmodernism.

For San Francisco, Johnson designed several buildings. The most controversial was the Neiman Marcus department store on Union Square, which speaker after speaker denounced at a Planning Commission hearing. His tower at 101 California Street was better received, although the 12 draped, faceless, hollow figures that adorned his building at 580 California Street were greeted with some disdain. Described as “The Corporate Goddesses” by Muriel Castanis, the figures that were sculpted by Johnson were, Johnson said privately, representations of the Board of Supervisors and the mayor.

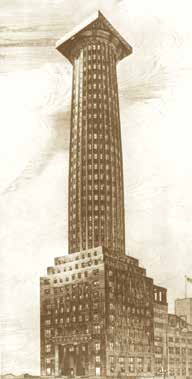

Whether any of these architects or their works expressed a “queer sensibility,” it was a heterosexual designer who submitted plans for the most homoerotic building yet proposed for the United States. In 1922, when the Chicago Tribune announced a design competition for its new headquarters building, Adolf Loos put forward a cylindrical skyscraper crowned with a massive capstone.

Loos’ design was not selected, but it did show how human anatomy could inspire a monumental creativity. The design was not a serious example of how “form follows function” in architecture, but it certainly followed Oscar Wilde’s advice that “one must always be a little improbable.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments