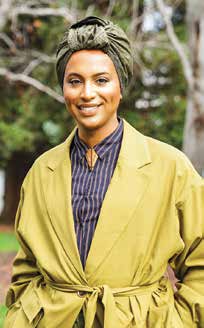

By Honey Mahogany–

I remember the very first time I actually vocalized my queerness. I was very young, just barely in pre-school. I remember that I was sitting with friends looking through one of my favorite picture books, a ballet interpretation of the story of Cinderella. As we flipped through the pages, we finally landed on the ballroom scene. The other boys quickly began pointing out the ballerinas that they wanted to marry, eager to stake their claim: that one in the blue dress, the one with the blonde hair … . Anxious someone else might beat me to it, and without thinking about what I was saying, I quickly blurted out, “I want to marry the prince!”

As soon as the words left my mouth, I wished I could take them back. I remember how quickly my cheeks got hot, even before I looked up to see the look of shock and disgust on the other boys’ faces. “Eew, that’s gross!” they said. “You’re not supposed to marry the boys; you’re supposed to want to marry the girls.” Yes, even at that young age, I knew that is how I was supposed to feel, but I didn’t feel that way.

Needless to say, I didn’t make a mistake like that again. I kept my queerness hidden as much as I possibly could, though, admittedly, I wasn’t very good at it. I remember how often I was told as a child to try and play more with the boys. I remember my father, in particular, being upset by this, and getting more and more angry with me, especially as I started to hit puberty. Looking back, I know now that he must have been scared for me. He must have been terrified by what it might mean to have a boy who didn’t like to play with other boys, but all I knew at the time was that my father was unreasonably short-tempered and that it caused me to pull away from him.

In the 8th grade our class was part of a district-wide story contest. The story we had to write was one where we found ourselves waking up in the body of the opposite gender. To say that I was excited about this assignment was an understatement. I mean, I had basically been dreaming this story every night since I was in preschool, and now, I had the opportunity to, if not make it real, then make it at least come to life by sharing it. As excited as I was, I was also paralyzed with the fear that I might reveal too much. But in the end, it was an assignment that I had to complete, so I set aside my fear and wrote the story. My friend Ann and I were chosen as having the top two stories of our grade. I remember my teacher gave me a knowing look after she said my name, as if she knew my story was a little too real, a little too earnest.

I didn’t end up actually coming out until I was well into my first year of college. Unlike the youth of today, when I was growing up it was still rare for people to come out while they were in high school. For me, there was also the added pressure of growing up the child of immigrants who came here from Ethiopia, a country that has been predominantly Christian since the 4th century, with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church being one of the oldest Christian churches in the world.

Even though I grew up in San Francisco, I was pretty sheltered. My closest friends and playmates were my cousins and second cousins whose parents had all moved to the Bay Area around the same time mine did. We spent every weekend at each other’s houses and many weekdays after school together. There was a very intimate and connected sense of kinship and love that I feel privileged to have experienced with my family. That closeness and sense of belonging was something that I treasured, and the idea that my coming out could possibly cause my family pain and even cause them to reject me was absolutely terrifying.

Going to college provided me with the opportunity to create some distance between myself and my family and that, in turn, allowed me the space I needed to explore my identity without fear of being found out or outed (this was before Instagram and Facebook after all). I ended up coming out to my close friends before my first semester was over, and before long, I got involved with the queer student association, the GLBTA, and began volunteering with the LGBT Center. In my sophomore year, I got in drag for the first time for one of my best friend’s student films. He approached me about playing the role because he said that I was the only guy he knew would also look good as a girl.

By my junior year, in addition to being an executive board member of the GLBTA, paid staff at the LGBT Center, and my burgeoning career as a drag queen, I also became the resident advisor for the Rainbow Floor, one of just a few LGBT-themed dorms in the country. And when I graduated, I received an award for outstanding service to the school and to the LGBT community, and yet I still had not come out to my family.

The summer after I graduated from college, I was working while traveling across the country as part of the National Student Leadership Conference. I would call home periodically to check in on my family, but after a while I felt that something was wrong. The phone calls became a bit strained for reasons I couldn’t quite figure out. I started getting a knot in the pit of my stomach thinking that somehow, they must know.

When I returned home from my summer job, my father picked me up from the airport. He seemed terse and distant, but that wasn’t necessarily out of the ordinary for him. When I finally arrived at home, it was quite late at night, and I was surprised to find my mother was still awake and that she said she wanted to talk to me. My parents sat me down at the kitchen table and explained to me that one of my cousins had found pictures of me dressed as a woman on my Flickr account. He had found them when I shared another folder of pictures from my trip that summer and shared them with his mother who shared them with all our other family members before finally telling my parents.

So, there it was, my opportunity to come clean. Most of what was said that night is a bit of a blur. I remember fragments, bits, and pieces—that my mother was steely cool, my father was angry, and I was sobbing as I imparted all the things that I had thought and done that I wished I could have shared with them, that I was afraid of disappointing them.

Over the next few weeks family members came to visit my parents to hear their grief and to talk to them about what to do. There were a few dramatic moments—my father at one point threatened to kill himself from the shame—but aside from that, the general mood was somber, and careful. I was spoken to by cousins who were supportive of me and wanted to let me know that they were there, and well-meaning uncles who wanted to share their views on sexuality and asked me how I knew I wasn’t interested in women unless I gave it a try.

A few days after I returned, my mother drove me to Ocean Beach to have a talk. She imparted on me how shocked she was; how when I was born, she examined me and watched me grow and how I was her perfect, sensitive, and kind son, and that didn’t mean I had to be gay. She said that she loved me regardless, and that she would always love me, but that she wanted me to at least try to change. At that point, my strong, steadfast, calm mother broke down into tears, and my heart broke along with hers.

My mother asked me to do her a favor and take some time away from the city and to go back home in Ethiopia. In her mind, I was surrounded by negative corrupting forces that I had to get away from, and she wanted me in an environment where she knew I would be surrounded by people she trusted. Unable to say no to my mother in that moment, I agreed. I did warn her that I didn’t believe it would change anything, but for her sake, I would go and give it some time.

My outing undoubtedly changed the course of my life. After my summer job, I had planned to return to Los Angeles where I had both a musical theater intensive and a research job waiting for me. I had been excited to start life as a fully-fledged adult with a job, my own place, and unburdened by school. I was still considering continuing on to grad school, but I wanted to take a year off to figure out exactly what I wanted to do, and like most young people in Los Angeles, I also intended on taking a swing at a career in entertainment. But now, all of that was gone.

Even though my trip to Ethiopia wasn’t what I had planned to do, I think it was the best thing that could have happened to me. While I was there, I was able to connect more deeply with my family and had the opportunity to not just learn or hear about the country of my forebears, but live there and experience it first-hand. I felt at home in a way I never had before in a sea of beautiful brown, caramel, and mahogany faces who all made me feel like I belonged.

After I returned from Ethiopia to go to grad school, my parents and I didn’t talk about the reason why I left. Things sort of very slowly started going back to normal. My dad never engaged me in a direct conversation around any of it, but occasionally he would mention that he saw a drag queen or something gay as a way of letting me know he was ok with it. After a few years I was able to have more conversations with my mother, in particular, about my queerness and eventually my gender identity. It took a while for her to fully come around, but we are now at a point where she fully accepts my partner and asks about him whenever we talk.

Looking back at this whole process, I wish I could have told my younger self that there is indeed light at the end of the tunnel. That yes, it will be scary, and there are definitely some rough patches, but that in the end you’ll survive, and your relationship with your family will be stronger for it … but in the end, I suppose I got through it all just the same.

Honey Mahogany, a Legislative Aide to Supervisor Matt Haney, is also an LGBTQ activist, performer, and singer. As a performer, Mahogany was featured in the fifth season of “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” becoming the first contestant from San Francisco. In 2018, Mahogany achieved another first as the first trans person to serve as co-president of the Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club.

Published on December 17, 2020

Recent Comments