By John Lewis–

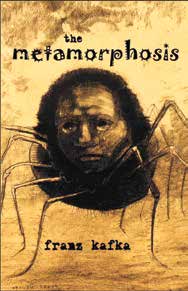

“Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams to find he had been transformed into a gigantic cockroach.” So reads the first sentence of Franz Kafka’s 1915 masterpiece The Metamorphosis.

Kafka and The Metamorphosis immediately enthralled me as soon as I encountered the book in my high school German class. Why was Gregor transformed overnight? What were his “uneasy dreams” that night? How in the world was Gregor going to get out of his most unfortunate predicament? As a teenager thirsting to understand the nature, meaning, and purpose of life (and sexuality), I felt as if Kafka was speaking to me and we shared a common path.

The events of 2020 reveal the enduring relevance of the story of Gregor Samsa. Although we weren’t turned into cockroaches this year, COVID-19 dramatically altered our lives overnight in a way Gregor might recognize. As millions of us “sheltered in place” and spent more time alone than ever before, we experienced isolation that recalls the painful separation from others that Gregor experienced when he became a big bug. Just as Gregor struggled to find the way forward when his life was turned upside down, so have we.

I also began to wonder whether my struggles with being gay back in high school were another reason I had found the story so compelling.

In high school and college, I understood the book as an allegory about the human condition and our apparently fruitless efforts to find or ascertain spiritual truth. Gregor’s plight as a cockroach and his efforts to survive and liberate himself are a metaphor for people’s search for freedom from suffering, isolation, and the apparent futility of life.

Like any timeless tale, this work can be interpreted in many ways. This year, I learned that The Metamorphosis can also be viewed as the Jewish writer Kafka’s cautionary tale about the precarious position of European Jews in the early 20th century. Scholars have read Gregor’s predicament as a metaphor for the anxiety European Jews experienced as Europe began to allow their assimilation into the broader society.

Gregor’s struggle symbolized both Jewish concerns about maintaining culture and identity amidst assimilation, and fear of ongoing anti-Jewish hatred and scapegoating. It seems no accident that Gregor was transformed not into a benign butterfly but, in fact, according to some translations a “monstrous vermin,” a well-known anti-Semitic trope. Gregor’s initially caring sister Greta eventually turns on him, saying they must get rid of “it.” Tragically, the Holocaust proves Kafka’s apparent fears to have been prescient.

The Metamorphosis speaks to me now as a queer parable as well. As a queer youth in 1970s Kansas City, I felt unable not only to express my sexuality and gender but also to come into touch with it internally. Even as I had positive experiences growing up and in high school, I felt enormous internalized pressure to conform to others’ expectations. Being different in any significant way was inconceivable to me. I had unknowingly donned an emotional, spiritual, and sexual straitjacket that resembled the large exoskeleton that trapped Gregor. I didn’t even know it, but I was emotionally isolated and struggling to become free without any idea of how to do it. Gregor and I faced similar problems.

Of course, back in the 1970s, much of American society viewed LGBTIQ people as menacing objects of disgust like cockroaches. From the Lavender Scare to Anita Bryant’s “Save the Children” campaigns, to Prop. 8, to stigmatizing transgender people, the political fear tactics characterizing LGBTIQ people as fundamentally dangerous to others sadly retains some of its force today, especially among politically conservative Christians. Gregor died alone of starvation after even his sister and parents abandoned him. We know all too well the continuing devastating effect of familial, religious, and societal homo-transphobia on too many LGBITQ people today.

Although The Metamorphosis does not have a feel-good ending of love and acceptance, one scholar commented that Gregor underwent a second transformation in the book—coming to embrace “his true form.” So too have millions of LGBTIQ people. Just as The Metamorphosis is a story about the search for freedom, our movement was originally known as Gay Liberation and we marched in Freedom Day parades.

Gregor never sacrificed his own heart and lost empathy and the desire to connect meaningfully with others even as they rejected him. Paradoxically, Kafka’s fictional tale of Gregor’s isolation, which we know reflects the writer’s own actual experience, reminds us that none of us are actually alone in our struggle to find peace, freedom, and happiness. Indeed, being reminded during the current pandemic that we are all struggling in different ways has helped me breathe easier.

Perhaps the genius of The Metamorphosis is its presentation of the human predicament for which we all must find solutions. Does Kafka point us to love? The marriage equality movement’s celebratory declaration that “Love Wins” brought a divided nation closer together by striking to the heart. It also may be a hope that sustains as we go forward.

Stuart Gaffney and John Lewis, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Published on December 3, 2020

Recent Comments