By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

From the fabled Queen Califia, for whom California is named, to the legendary Hua Mulan to the very real Joan of Arc, women have gone to war, some concealing or revealing their true nature by enlisting and serving as men. During the American Civil War especially, some 400 women and girls disguised their birth genders to join the Union and Confederate Armies, although only one, as far as we know, identified as a man before enlisting and maintained his secret for the next 50 years later.

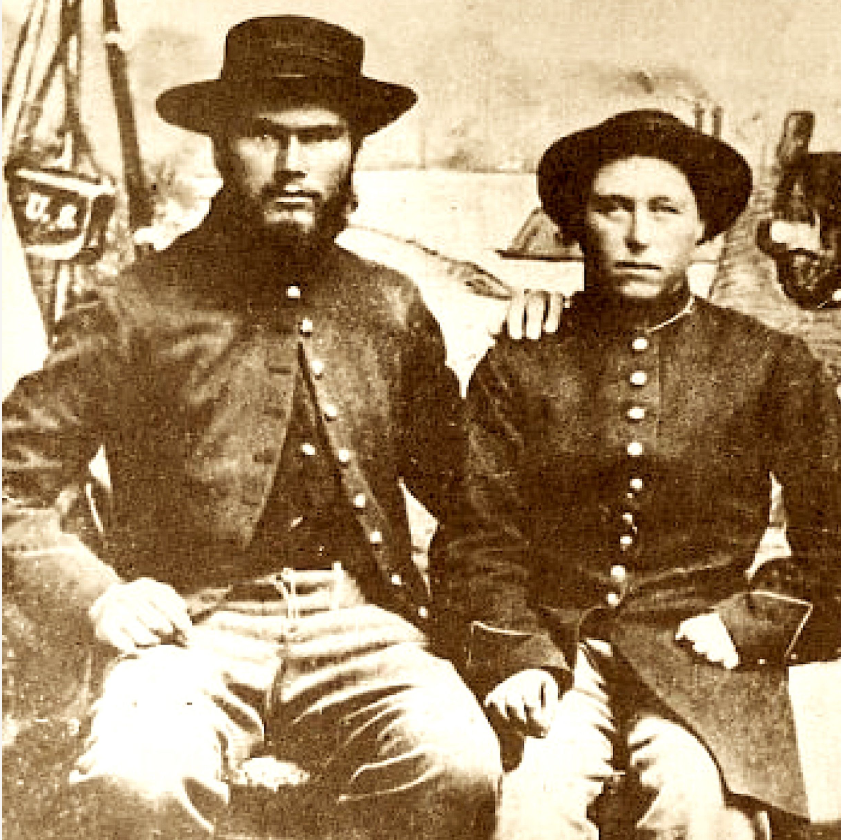

Born on Christmas Day, 1843, in Clogherhead, County Louth, Ireland, and recognized then as female, Albert D. J. Cashier spent his entire adult life as a man. Very little is known about him before he volunteered for the United States Army in Belvedere, Illinois, on August 6, 1862. According to The Company Descriptive Book of the 95th Illinois Infantry, his regiment, Cashier had blue eyes and auburn hair. Standing only 5’3” and weighing 110 pounds, he was the shortest, smallest soldier in the unit.

In 1862, enlisting in the military was relatively easy. Both the Union and Confederate armies forbade women from soldiering, but no birth certificate or other proof of identity—and often no physical examination—was required. Volunteers had to be at least 18 years old to join the Union Army—the Confederacy had no minimum age requirement—but many recruiters simply ignored the law. Some 20% of Civil War soldiers were underage, so a smooth-faced, very young-looking Cashier would have seemed unremarkable.

Cashier became a much-admired soldier, esteemed by the other men in his regiment for both his military demeanor and his reckless daring, enduring the long marches, the rigors of camp life, and the endless trauma of war. “In handling a musket in battle,” Gerhard Clausius wrote later, “he was the equal of any in the company.” Considered to be one of the most dependable men in his company—and because of his “apparent abandon”—he was frequently selected for vital assignments.

His bravery in combat became legendary. On one occasion, while part of a skirmishing expedition that was reconnoitering near Vicksburg, Mississippi, Cashier was captured by Confederates. Undaunted, he seized a gun from his guard, knocked the man down, and fled back to the Union camp. On another, according to Sgt. Charles Ives of the 95th Illinois Infantry, he “gained distinction by climbing a tall tree to attach the Union flag to a limb after it had been shot down by the enemy.”

Ives also remembered a skirmish “when our column got cut off from the rest of the company because we were too outnumbered to advance. There was a place where three dead trees piled one on top of another formed a sort of barricade.” When “the rebels got down out of sight,” Cashier ran to the front, “hopped on the top of the log and called, ‘Hey! You darn rebels, why don’t you get up where we can see you’ and ‘get a shot at you.'”

Cashier stayed with his regiment until it was disbanded on August 17, 1865. He and his companions had traveled some 9,960 miles—1,800 of those on foot—and fought in 40 battles and skirmishes, Besides the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863, he saw combat during long campaigns in Arkansas and Missouri the next year. On April 9, 1865, the day Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses Grant at Appomattox, he was engaged in the struggle to capture Fort Blakely in Alabama.

How did Cashier escape detection for three years while serving with hundreds of other men? He mostly kept to himself. According to Eli Brainard, “He never took part in any of the games with the rest of the men. He was very quiet.” Some of the men, he told a special examiner of the Bureau of Pensions in 1914, “used to talk about his having no beard,” but “I never heard any talk in the army about him not being a man.”

Cashier also found every opportunity to avoid bathing, dressing, and sleeping in close quarters with other soldiers. “One time,” Ives remembered, “we went into barracks at what is now known as Camp Grant … . All of the bunks were double, but over in the one corner there was a single cot. Cashier asked me if he might have that cot. I consented and thought nothing about it.” No one could remember either the names of his bunkmates or that he ever had one.

After the war, Cashier returned to Illinois, eventually making his home in the small community of Saunemin, about 100 miles southwest of Chicago. Never changing his gender identity or appearance—a shaving mug and brush were displayed among his few belongings—he lived there for the next 50 years, working as a farmhand, janitor, street lamplighter, and handyman. Unlike his neighbors who identified as female, he also voted in elections—women did not have that right then—and collected a veteran’s pension.

In 1911, in his late 60s, Cashier broke his leg in an automobile accident. No longer able to work, he moved into the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ home in Quincy, Illinois. Three years later, now suffering from dementia, he was relocated to the Watertown State Hospital in East Moline, where staff discovered his birth gender. What happened next was tragic. “She was compelled to put on skirts,” Ives wrote later. “She was as awkward as could be in them. One day she tripped and fell, hurting her hip. She never recovered.”

The Pensions Bureau now conducted a thorough investigation, amassing 191 pages of documents, depositions, affidavits, certificates, and newspaper accounts. Its concern was not that a woman had served during the Civil War against all regulations, but “to determine whether the pensioner is identical with the soldier of record and “whether the “person at the Soldiers’ Home” “is identical with the original pensioner.” Its examiners interviewed many of the soldiers who had served with Cashier, who well remembered him. All regarded him highly. He kept his pension.

Fully exonerated in his identity, Cashier died on October 10, 1915. As a loyal soldier for the Union, he was buried in uniform with full military honors. To mark his resting place, the government set a gravestone that, recognizing who he was in life, bore the inscription “Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.” His one-room home of many years at the corner of Center and Maple Streets in Saunemin, Illinois, is now a historic site.

Besides having an exemplary service record, Cashier was the only soldier identified as female at birth, as far as we know, who completed a tour of duty, was mustered out with his regiment, and received a Civil War pension. However Cashier saw and understood himself, he showed tremendous valor under fire for three years during this time in the Army and great courage and independent spirit for the rest of his life.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006) and “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on December 21, 2023

Recent Comments