By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

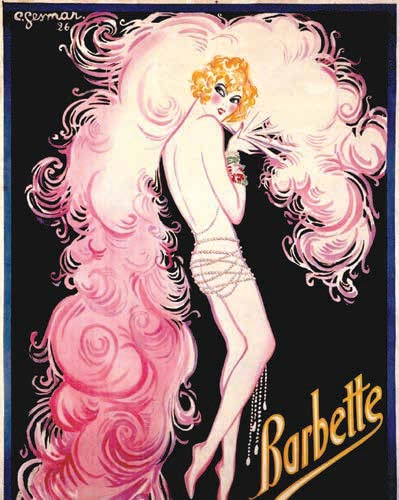

To those who did not know or had forgotten, the revelation was electrifying. To those who knew, it was still exhilarating. A beautiful young woman, apparently adorned in nothing but glittering jewels, had performed a breathtaking aerial and acrobatics act, then descended to the stage, removed her headdress and revealed to her adoring audience that, in fact, she was a man. During the years between the World Wars, audiences first in Paris, then in all of Europe and beyond were mesmerized by the sensation that was Barbette.

Critics especially were impressed. Janet Flanner, whose “Letter from Paris” appeared regularly in The New Yorker, called him a “new Phaethon” (whose father was the sun god Helios) and termed his elegant drop to the stage at the close of his performance a”chute d’ange” or “angel’s fall.” Writer, filmmaker, visual artist, and critic Jean Cocteau, one of the most influential creative minds of the 20th century, described his performance as, “Ten unforgettable minutes. A theatrical masterpiece.” Barbette, he said, was “an angel, a flower, a bird.”

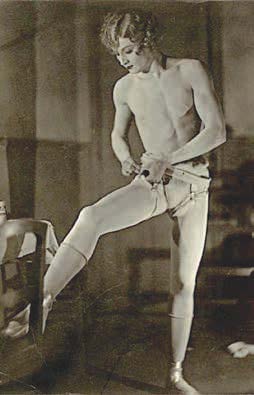

He went even further in his famous essay “Le Numéro Barbette,” published in 1926. On stage, at a time when people thought about a person’s gender, if they thought about it at all, as being either male or female, Barbette moved easily and fluidly between the two identities. He first appeared as a woman—who “eclipses the prettiest girls … on the program”—then stripped to a near naked androgyny, performed his specialties, and after seemingly endless curtain calls, removed his headdress and left the stage as a man.

Here was something new, something unique, something shocking to audiences: a performer who dared them to question their ideas of gender identity and sexual attraction. Earlier female and male impersonators, dating back to the earliest days of the theater, rarely did that. Either they disguised their true self completely from the public—the truth, when revealed, often destroyed their careers—or they made no secret of it, appearing openly as someone performing “a very finished piece of acting.” Anything else would have been considered extremely distasteful.

For Cocteau, however, “the essence of Barbette [was] as neither a man impersonating nor transformed into a woman, but instead as a being that takes advantage of the fluidity of aesthetics and theatrics to render gender and sex amorphous, constantly in a state of movement.” By combining “feminine grace” and “masculine strength,” by moving effortlessly between them, he challenged the conventional definitions and enforced ideas about what was male and what was female. We are each of us much more complicated than we thought.

The man Cocteau called “an angel, a flower, a bird” was born Vander Clyde Broadway on December 19, 1899, in Trickham, Texas, a state not known at the time for a welcoming attitude toward female impersonators. His family moved to Llando, the “deer capital of Texas,” then to Round Rock, a few miles from Austin. A visit to a traveling circus changed the course of his life. He became enamored with the show’s tightwire act and began practicing on a rope he installed in his family’s backyard and anywhere else he could find.

After graduating from high school as the valedictorian of his class at age fourteen, he answered an advertisement to become one of the Alfaretta Sisters, billed as the “World Famous Aerial Queens.” During his interview Ms. Alfaretta told him, he remembered, “that women’s clothes always make a wire act more impressive … and she asked me if I’d mind dressing as a girl. I didn’t, and that’s how it began.” He later toured with Erford’s Whirling Sensation as one of three girls dressed as butterflies.

Barbette debuted as a solo performer at New York’s Harlem Opera House in 1919. His success seemed assured. “A distinct novelty,” The New York Dramatic Mirror wrote in its review, “she works hard and fast and her stunts are quite thrilling. She is liked so well, she is called out to make many bows.” In addition, “she is not a bad looking girl at all.” The greatest moment came soon after, when “she pulls off her wig and ‘she’ surprises everyone by being a man.”

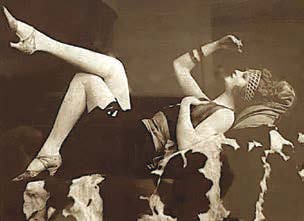

Although he began as the opening act, Barbette quickly became the star attraction. Francis Steegmuller wrote in 1969 that he believed her performance was so immediately successful “because of its surprise element—his revelation, at the end, of his masculinity—which to him was always only one part of the whole.” Whether anyone at the William Morris Agency agreed, they sent him to London, and then to Paris, in the fall of 1923, where he became one of the greatest and most influential stars of the decade.

If nothing else, Barbette knew how to ensnare an audience. He first appeared high above the stage against black velvet curtains, illuminated by a single spotlight. As Harry Daley described him, “She slowly descended a great stairway magnificently dressed in white ostrich feathers, delicately discarding them one by one in a sort of floating strip-tease.” After displaying spectacular skill and daring on a tightrope and trapeze, “swinging upside down with fluttering curls and looking so helpless and cuddly,” she “leapt down on to the stage to thunderous applause.”

Now an international sensation, Barbette returned to the United States in 1927 to headline at the Palace Theatre in New York, the ultimate achievement in vaudeville. Variety wrote, “As an impersonator, Barbette will fool anybody, as an aerial artist, he is superb.” Success then followed success. In 1935 he appeared on Broadway in Jumbo, which ran for a then-remarkable 233 performances. Sadly, his stage career ended only three years later, when he contracted poliomyelitis while performing at New York’s Loew’s State Theatre.

After several years of physical therapy, he became “a trainer, trying to give young present-day acrobats some faint idea of what a refined act can be,” then worked as a consultant for stage and film productions, including Disney on Parade. By the time he died on August 5, 1973, he had already achieved immortality because “no one,” as Jacques Damase wrote in A History of the Paris Music Hall, “went further in the cult of sexual mystification than this young man who transformed himself into a jazz-age Botticelli.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBT Past

Published on July 27, 2023

Recent Comments