By Imani Rupert-Gordon–

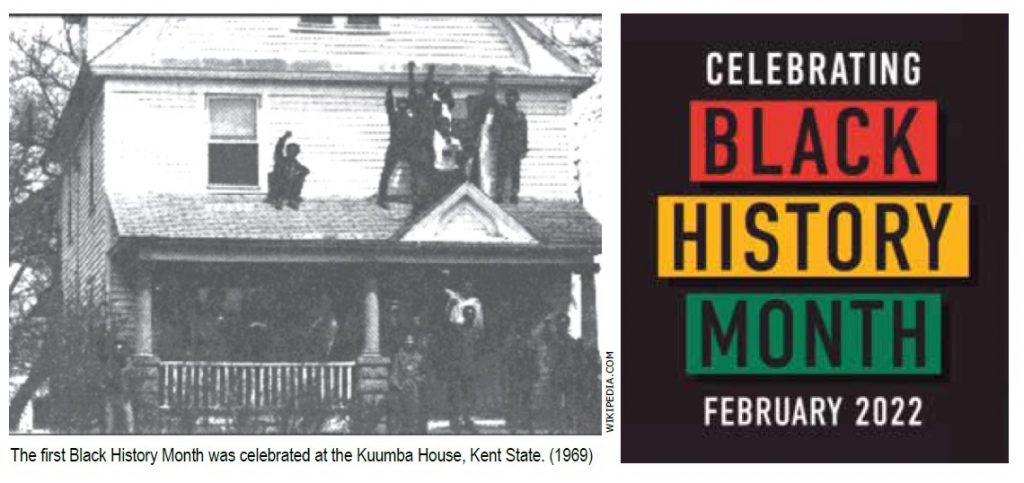

February is replete with obligatory Black History Month statements coming from corporations to politicians who actively work against Black communities most of the year and think of Black History Month as solely a symbolic celebration. In this moment, when we are dealing with renewed attacks on our ability to teach and learn our history, it’s important to remember the fundamental radical demand that lies at the core of Black History Month: that our place in history is spoken and that our stories are told.

This resonates with me, because right now, many of our communities are fighting to have our histories taught. What we learn in school doesn’t just give us knowledge; it communicates priorities. It tells us the things we should value, and it frames our truth. And when you don’t see yourself reflected in that set of priorities, it’s easy to feel like you are ancillary in our history and our future. And it’s even easier for people to treat you that way.

I remember when I was in high school, some friends and I went to see the movie Amistad. I realized that everything I understood about the Amistad case was taught to me by my parents. My two friends and I were all in Advanced Placement History, then Advanced Placement Government, and we stood there in front of the movie theater grappling with the reality that there were large and important parts of our history that were not being taught to us in school, and there was a consequence to that.

For the first time I realized, perhaps, that was intentional.

Years later, I was falling in love with a woman for the first time when I realized that I didn’t know anything about the LGBTQ rights movement. I remember the internet search, thinking that surely, something is going to jog my memory any second now.

It didn’t. I learned about the Stonewall uprisings for the very first time that day. It wasn’t until years later that I learned of the contributions of trailblazers like Marcia P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Stormé DeLarverie.

I was an adult when I met someone outside of my family that had ever heard of Juneteenth. I was in college when I took my first classes in African American studies and realized that I wasn’t just learning something for the first time, I was unlearning too. And what I had to unlearn was the dangerous myth that people like me—who looked like me, who loved like me—didn’t play a role in our history. The truth is that we were central to it. I wonder where we would be if more people realized that.

When we don’t learn our history in school, it doesn’t just create a void waiting to be filled. It gives the impression that it’s possible to understand how history unfolded without understanding the contributions of Black people, of LGBTQ people, of immigrants, of people with disabilities, and people from dozens of other underrepresented identities. It communicates that there are some people who are less important than we are, and it makes it harder to see there was a void to begin with. And that changes the way we are able to contextualize the world and our place in it.

Sharing a more complete and honest history prepares us to make better decisions as advocates, and as citizens. For instance, when we have a deeper understanding of how Jim Crow Laws undermined voting rights, it’s easier for us to recognize the historical significance of the voting rights bills failing to pass the Senate this year, and what the long history of voter suppression represents.

Opponents of justice know this. It’s why we continue to see the efforts to keep groundbreaking research like the 1619 Project and other lessons about the centrality of the slave trade in our history out of schools. It’s why we see legislative efforts to erase the LGBTQ community from history with “Don’t Say Gay” bills. And why we continue to see efforts to ban books that will tell our stories more fully. Because teaching our history tells us that our stories matter and, so too do we. And in a political moment like this one, celebrating Black History Month isn’t symbolic. It’s radical.

Imani Rupert-Gordon is the Executive Director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights.

Published on February 24, 2022

Recent Comments