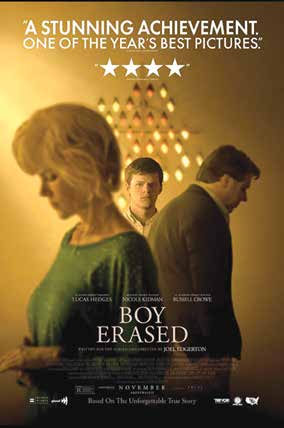

The well-meaning drama Boy Erased, based on Garrard Conley’s memoir about his experiences in a gay conversion therapy program, is a TV movie-of-the-week dressed up as Oscar bait. Written and directed by Joel Edgerton, the film, which opens November 2 in the Bay Area, is best geared towards heterosexuals unfamiliar with the insidious practice.

At the start of Boy Erased, Jared (Lucas Hedges) is being taken to a daily refuge program run by Victor Sykes (Edgerton) to “assess” and “cure” him of his homosexuality. Jared’s parents, Marshall (Russell Crowe), a Baptist preacher, and Nancy (Nicole Kidman), a bleach-blonde Southern Belle, have decided this treatment is the best—if not only—option for their son.

As a series of extended flashbacks shows, however, Jared is not guilty of sexual sin—as Sykes and his parents believe—rather, the totality of his sin is desire. He claims to “think about men,” but he does very little acting on his same-sex attractions. Oddly, Jared’s character presents himself more as bi-curious than gay, as if Edgerton wants to make Boy Erased palatable to the very audience—straight parents—that needs to hear the message.

And the message is important; the horrors of conversion therapy have more negative than positive effects on youth. (Statistics in the film’s end credits indicate 36 states still allow gay conversion therapy and 700,000 LGBTQ people have been subjected to it.) But Edgerton cudgels viewers with a slow-motion sequence in which one of the boys in the program is literally beaten repeatedly by family members and other folks, as if to knock the gay out of him. It is an obvious and heavy-handed scene in a film that often lacks subtlety and nuance.

Many of the characters in Boy Erased try to “pray the gay away,” and there are several discussions about behavior and choice— debating if LGBTQ folks are “born this way” or “choose” to engage in queer activities. A preachy comment about being born a football player tries to defend the program’s position, but a better sequence, in which Jared visits a doctor (out gay actress Cherry Jones) who discusses science, God, and free choice, shows that there can be clearer thinking on homosexuality and faith.

Many of the characters in Boy Erased try to “pray the gay away,” and there are several discussions about behavior and choice— debating if LGBTQ folks are “born this way” or “choose” to engage in queer activities. A preachy comment about being born a football player tries to defend the program’s position, but a better sequence, in which Jared visits a doctor (out gay actress Cherry Jones) who discusses science, God, and free choice, shows that there can be clearer thinking on homosexuality and faith.

Other comments by Sykes and the teens address what it means to be a “real man,” “faking it until you make it” and “becoming the man you are not.” While these agenda-driven approaches get at the core of why folks believe in conversion therapy, a manipulative scene of Sykes bullying the teens is cringe-inducing for all the wrong reasons. Viewers are supposed to feel pity for the youth, but the characters are too one-dimensional to generate empathy. Several of the program’s attendees aren’t fully formed and are distinguished more by their hair color or body type than any other characteristic.

As Jared fulfills one of the program’s requirements, cataloging his “moral inventory,” he reflects back on his relationships with Henry (Joe Alwyn) and Xavier (Theodore Pellerin), which are respectively tough and tender. What transpires in these scenes—and should be left for audiences to discover—seems very real and impactful, but Jared’s internal responses to these potential boyfriends are not articulated enough to fully illuminate his character.

Jared is repeatedly being asked, “Do you want to change?” His answer, yes, may be going along to get along, but Hedges’ performance never convinces; he never makes Jared’s internal struggle feel real. He plays Jared’s emotional turmoil by simply having a perpetually troubled look on his face. Jared cries in a bathroom stall after a difficult encounter with someone he admires and reacts with a glare when someone calls him a “faggot.” Even a scene of self-hating, where Jared throws a rock at a sexy billboard ad, seems forced. Hedges is supposed to be a “boy erased,” but he doesn’t disappear into the role.

What the film does best is to focus on the parents and their role in Jared’s situation. Nancy talks about “hurting to help,” and justifies her actions by telling her son that “parents want to protect their kids,” but it is not until she senses Jared is in danger in the program that she starts to change her opinion and a ferocious Mama-Bear mode kicks in to stop the abuse/treatment. Kidman may generate applause from viewers when she finally does right by her son (that’s not much of a spoiler) but the actress does seem miscast in her role.

In contrast, Russell Crowe is able to silently express Marshall’s internal conflict well. His awkward discussions with Jared give the film some of the juicy dramatic tension Boy Erased sorely lacks. In support, Edgerton plays Victor Sykes broadly, like a cartoon villain.

Boy Erased is a clunky redemption tale. It tries too hard to be crowd-pleasing, and as a result, glosses over the issues at stake and how teens like Jared are subjected to reparative therapy that does more damage than good.

© 2018 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Recent Comments