By Amy Sueyoshi–

On July 1, 2015, the Respect After Death Act (California Assembly Bill 1577) enabled transgender people to record their chosen gender on their death certificates. At least three Asian trans men stood at the center of the passage of this bill. When Chinese and Polish American Christopher Lee took his life by suicide, the coroner listed him as female on his death certificate. Troubled by the mis-gendering, Chinese Mexican Chino Chung brought the death certificate to the attention of the Transgender Law Center, which initiated and lobbied for the passage of AB 1577. Three years later, Japanese American Kris Hayashi stood at the helm of the Transgender Law Center as its Executive Director when the organization celebrated the passage of the bill. Yet, Asian American involvement has largely been erased in the passage of this bill, as well as other defining moments in American consciousness. Still, queer APA changemakers have existed throughout U.S. history and have become increasingly “out and proud,” engaging in activism at the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality.

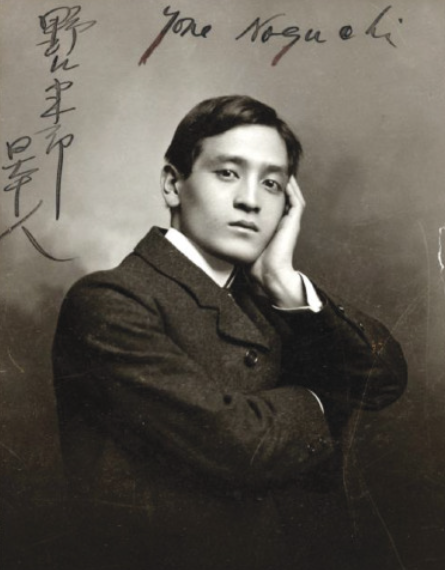

In 1899, Kosen Takahashi, an illustrator for the San Francisco serial Shin Sekai, missed kissing fellow Japanese immigrant Yone Noguchi, who had gone tramping to Los Angeles. Noguchi, a burgeoning poet, would become a key figure in the modernist movement even as he remains more known today as the father of Asian American artist Isamu Noguchi.

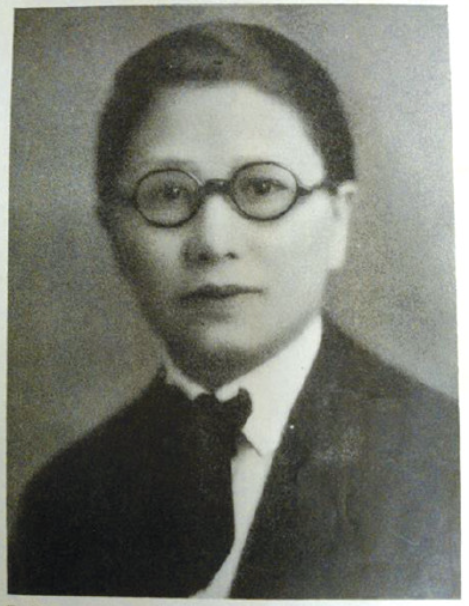

Ten years later, Margaret Chung began her medical practice as the first woman surgeon of Chinese descent. Chung, who was also known as “Mike,” wore mannish attire and drove a sleek blue sports car around San Francisco. She led many, including poet Elsa Gidlow, to speculate that she might be a “sister lesbian.” Gidlow actively courted Chung, drinking bootleg liquor at a local speakeasy of Chung’s choosing in North Beach during the Prohibition. In the 1940s, Chung would go on to fund the establishment of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) and Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services (WAVES) while writing love notes to burlesque performer Sophie Tucker, who was known as “the last of the red-hot mamas.”

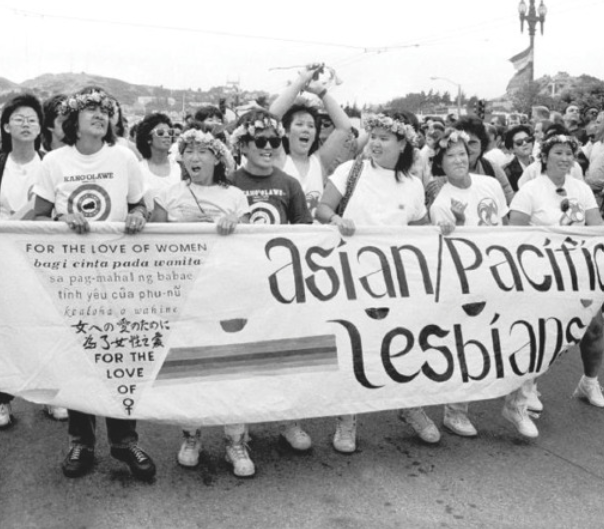

The second half of the twentieth century allowed for more active queer and trans APA political engagement. Filipina Rose Bamberger in 1955 invited six women to her San Francisco home, including Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, to map out the formation of what would become the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first lesbian civil and political rights group in the United States.

Throughout the 1960s, sex worker and activist Tamara Ching of Native Hawaiian, Chinese, and German descent, fought back against police harassment with other street queens in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. She was a regular at Compton’s Cafeteria, which in 1966 would become an early site of queer and trans resistance three years before the rebellion at New York’s Stonewall Inn that has become a signpost for the beginning of the modern gay and lesbian rights movement. In 1977, Ching would ask San Francisco’s Coalition of Human Rights to support what could be the earliest queer Asian support group, called Gay Asian Support Group (GASG).

For sure, queer Asians took up critical roles in rising movements for racial equity and women’s rights. Activist Gil Mangaoang co-founded the Kalayaan Collective and became an early member of Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP), the first revolutionary Filipino nationalist group in the United States. KDP appeared to be the only organization within the Asian American movement that allowed for queer members, with at least ten lesbians and two gay men.

P.E. teacher Crystal Jang immersed herself in the lesbian feminist movement and joined the fight against the 1978 Briggs Initiative that would have legalized the firing of all gay and lesbian teachers and those who supported them. Later, in the 1990s, Jang became the middle school coordinator for the Office of Support Services for Sexual Minority Youth and Families, the first office of its kind in the nation, creating K–12 curriculum to address issues of bullying, antigay discrimination, and sensitivity to alternative families. In Michigan, Helen Zia formed American Citizens for Justice in the 1980s in response to the brutal beating murder of Vincent Chin by two white autoworkers. Zia led what is considered a watershed moment for pan-Asian American civil rights organizing.

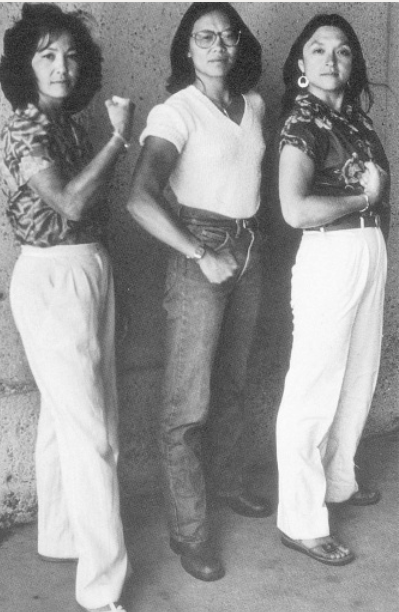

The most publicly visible Asian lesbian during the 1980s may well have been Kitty Tsui, known not just for her poetry, but also bodybuilding, as she won medals in the Gay Games. Her muscled body appeared in the renegade lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs in 1988 and 1990, as well as in New York City’s Village Voice. In 1995, she published Breathless, a book of SM erotica in which adventurous sexuality mingled with fermented bean curd and bitter melon. Tsui with numerous other Asian lesbians rode a rising tide of women writers, enabled by the Women-in-Print movement in which Korean American Willyce Kim played a formative role. As if in direct defiance of the rising conservatism of the 1980s, a proliferation of potlucks, conferences, newsletters, and softball teams accompanied the growing number of publications by women. Zee Wong sat as a central node for these social events, hosting lesbian house parties, organizing picnics in Golden Gate Park, and forming a women of color softball team called Gente that never won a single game.

Within a few years, however, the AIDS epidemic would cast a shadow on soaring queer activism at the beginning of the 1980s. Steve Lew served a critical role in the early efforts to address AIDS as a key organizer, educator, and role model for other HIV-positive men. In 1990 when Vince Crisostomo left New York and traveled across the country, he found community and family with Gay Asian Pacific Alliance (GAPA), the Asian AIDS Project, and particularly with Lew. Crisostomo, who is Chamorro, became the first publicly out HIV-positive Pacific Islander at World AIDS Day in 1992 and returned to Guam to become the executive director for the first funded community-based organization to do AIDS work in the Pacific.

Trans Filipina Nikki Calma, better known as “Tita Aida,” who also worked at the Asian AIDS Project in the 1990s, became a community icon through her advocacy work, serving as a host for countless fundraisers, and being one of three women to be featured in the first API transgender public service announcement in 2008. South Asians too more prominently formed queer groups, first in Brooklyn and later in the San Francisco Bay Area. Anamika and Trikone addressed the specific needs of LGBTQ people of South Asian descent from countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. The two organizations would be part of a half dozen South Asian groups that emerged in the following years across North America, the United Kingdom, and India. For many of these groups, the rise of the worldwide web facilitated connection. In Los Angeles, membership to a Vietnamese women’s group called Omoi increased exponentially alongside the growth of the internet.

In the twenty-first century, a younger generation of queer APIs are taking interest in the histories of their LGBTQ predecessors. API Equality in both Northern and Southern California has implemented oral history projects in the past decade and has sponsored Wikipedia Hackathons on API queer history. In the words of queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, queerness can then be understood as “part love-letter to the past and future” to aim towards “a utopia filled with surprise and imagination.” As we enter a dark chapter of queer and trans rights, hold close Muñoz’s call for imagination while we work collectively to forge a future filled with surprise if not immediate joy.

Amy Sueyoshi is the provost at San Francisco State University, where she previously served as the dean and associate dean of the College of Ethnic Studies. They hold a Ph.D. in history from UCLA and a B.A. from Barnard College. They have authored two books titled “Queer Compulsions” and “Discriminating Sex,” and are currently finishing up a third book on queer and trans APA history. Sueyoshi is also the founding co-curator of the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco.

LGBTQ+ AAPI Trailblazers

Published on May 8, 2025

Recent Comments