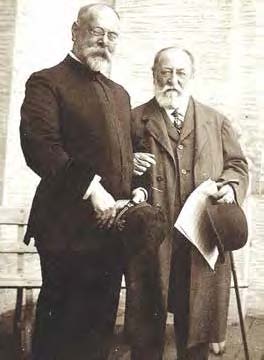

Camille Saint-Saëns and La Loïe Fuller at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition

In 1915, San Francisco gave a party and invited the world. Intended to delight in the completion of the Panama Canal, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition much more celebrated the renaissance of the City after the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906. More than 18 million people attended, including two world famous members of what we would call our LGBT communities: the venerated composer Camille Saint-Saëns and the renowned dancer La Loïe Fuller.

In May 1915, Saint-Saëns, then almost 80 years old, travelled the 5,500 miles from his home in France to San Francisco to debut his new work, Hail! California, commissioned by the Exposition as its official composition. Typically he favored more exotic destinations in North Africa, where he went, by his own admission, as much for the waifs as for the waters.

Saint-Saëns was feted throughout his visit, although he did not attend any parties here dressed as soprano Caroline Carvalho, who had sung Marguerite at the premiere of Gounod’s Faust, and for which he was famous among dear friends in Paris; no composer since Mozart wore a wig to greater effect. Neither did he dance in a tutu, which reputedly he effected to entertain fellow composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky, a frequent visitor to the City of Light.

Hail! California was premiered at the Exposition in Festival Hall, which stood near what is now the intersection of Pierce Street and Toledo Way. It delighted the audience of 4,000, but never entered the repertoire. Saint-Saëns’ visit did result in a more enduring musical legacy, however, in his Élégie, Op. 143, which he composed while in San Francisco.

Saint-Saëns was still in the City when La Loïe Fuller, arguably the most acclaimed dancer in the world, appeared at the Exposition. Before there was Isadora Duncan, whom she encouraged, or Ruth St. Denis or Martha Graham, there was Fuller, a natural and spontaneous performer whose ideas and innovations became the foundations of modern dance.

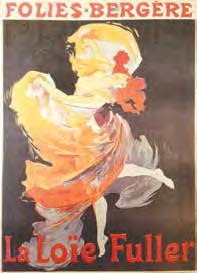

Born Marie Louise Fuller in 1862 near Chicago, Illinois, she began her theatrical career as a professional child actress and later performed as a skirt dancer in vaudeville and circus shows. She became well-known in America, but felt that her work was not being taken seriously by the public. That changed when she moved to Europe, where her 1892 debut at the Folies Bergère in Paris brought her international celebrity.

As a woman who loved women, Fuller had little interest in appearing as a tutued ballerina locked in her prince’s loving gaze, surrounded by admiring male courtiers, an object of masculine desire. No dying swans, no unrequited peasant girls, no suffering Cinderellas for her. Instead, she transmuted herself into a kinetic sculpture on stage, presenting what critics described as “transformative imagery of hypnotic beauty” and “the dizziness of soul made visible by artifice.”

To accomplish this, Fuller created a new methodology of movement and presentation. She devised her own costumes, made from yards and yards of gossamer thin silk. She designed her own lighting, performing in a rainbow of colors provided by revolving discs with tinted gels, another of her innovations. She did away with scenery, illuminated the stage from below, projected images onto her clothing, and choreographed shadows and silhouettes. Except for the music, every aspect of her performance was hers.

Long separated from her husband—he was wed to her and two other women when she left him—she found personal happiness with Gabrielle Sorère, a member of her company, who became her lifelong companion, manager, artistic collaborator, and co-founder of an all-woman dance company in 1907. Always innovating, their final work together was the 1921 film The Lily of Life, which Sorère directed. It was one of the first motion pictures to use a negative print to distinguish reality from illusion. A couple for more than two decades, they were parted only by Fuller’s death in 1928.

When Fuller came to the Exposition in 1915, she was 53 years old and only rarely performed in public. For the celebration, however, she appeared on stage with her troupe of Parisian students, whom she called her “Muses,” in a series of dance recitals that included Prelude l’apres-midi d’un faune by Debussy; Grieg’s Peer Gynt (Fuller took the role of the Mountain King); and more. The ensemble later danced under the rotunda of the Palace of Fine Arts, hoping to raise money to preserve it after the fair closed.

Fuller helped to leave another lasting contribution to the City, through the generosity of her great friend Alma de Bretteville Spreckels. The two women met in Paris in 1914, where Fuller introduced her to the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Alma purchased a number of his works directly from him, which she put on display in the Exposition’s French Pavilion, a copy of France’s Palace of the Legion of Honor. To house her collection after the exposition closed, she had an exact replica of the pavilion built in Lincoln Park, a copy of a copy, which opened in 1924. Fuller herself continues to be an influence on contemporary dance.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments