By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

The Palace of the Argentine National Congress (Palacio del Congreso Nacional Argentino) in Buenos Aires on August 20, 2021, was “illuminated with the colors of diversity” to remember author, historian, and activist Carlos Jáuregui on the 25th anniversary of his death, and in “honor of his legacy of struggle and freedom” for LGBT people. Known as the Day of Activism for Sexual Diversity (El Día del Activismo por la diversidad sexual), the annual observance celebrates one of the most important social and political leaders in the history of the nation.

Jáuregui embraced activism in 1981 after attending his first gay pride parade in Paris. “I cried like never before when I saw the first march,” he remembered. “It was incredible.” He had discovered that “it was possible to organize as a community,” to build a “clear, concrete political movement that fought for very precise demands”: human rights for LGBT people. Although he had no experience as a political activist, he “was certain that I had found what I really wanted to do.”

Jáuregui returned to Argentina in 1982. After the repressive military dictatorship was overthrow and democracy restored the next year, he became instrumental in shaping the philosophy and establishing the goals, strategies, and tactics of a new generation of LGBT activists. Early on he recognized that visibility was “the strongest resource that the gay movement has.” Not only would it empower LGTB people to feel free and proud, but it also could eventually change public opinion about a community and a movement that was misunderstood by so many.

In April 1984, he co-founded and became the first president of the Comunidad Homosexual Argentina or CHA (Argentine Homosexual Community), in large part because he was willing to be public about his sexuality; at a time when LGBT people had no legal protections—many feared what the attention might bring them—but Jáuregui welcomed it. For him, visibility was not only a matter of pride, but also it was a form of political activism. “In a society that educates us for shame,” he wrote, “pride is a political response.”

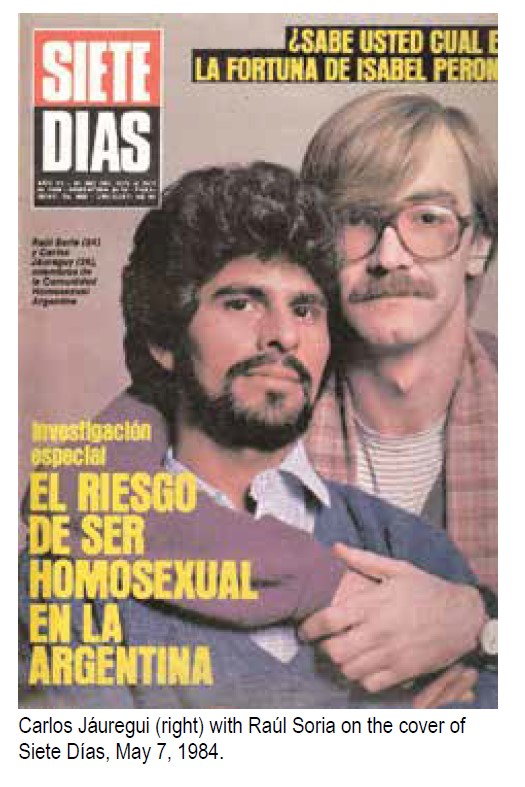

Jáuregui promoted visibility any way he could. The following May, all of 26 years old, he became very public when he and activist Raúl Soria, 24, appeared on the cover of the Argentine magazine Siete Días (Seven Days), identified as “Membros de la Comunidad Homosexual Argentine.” Their loving embrace was the first time two gay men freely and openly declared their homosexuality in the national media while also showing the deep affection they could have for each other.

By the time Jáuregui completed his term as president of the CHA in 1986, he was the most famous homosexual in Argentina: appearing on television, writing articles for magazines and newspapers, publishing the pioneering La homosexualidad en la Argentina (Homosexuality and Argentina), working to change public views of HIV, and openly discussing the challenges he had living with the virus. Still, he had few legal rights as a gay man. When his partner Pablo Azcona died in 1988, he was forced to move from the apartment they shared.

In 1991, Jáuregui co-founded Gays por los Derechos Civiles (Gays-DC or Gays for Civil Rights) with his friend and activist César Cigliutti, calling it a “less homocentric” organization than CHA. The next year the two men brought together a group of community leaders to plan a march to increase the visibility of the LGBT communities of Buenos Aires and to celebrate their existence. Not everybody agreed it was a good idea, but Jáuregui insisted. “We have to take the streets. It’s for our rights.”

On June 28, at night and in the middle of winter in his country, Jáuregui led the first Marcha del Orgullo LGBT de Buenos Aires (LGBT Pride March) for “freedom, equality and diversity.” The 200 or so participants—many wearing cardboard masks so they would not risk their livelihoods or their lives—found only empty streets, however, until they reached the Plaza de Mayo in front of the Presidential Palace (Casa Rosada). There they discovered a teachers’ demonstration just ending, but the media still present.

The reporters, intrigued by protestors carrying posters that identified them as “Transsexuals for the Right to Life and Identity” and the “Argentine Gay Lesbian Integration Society,” among others, stayed to cover it. They demanded the repeal of the laws that criminalized homosexuals, transvestites, and transgender people; legislation that allowed people to record their chosen name and gender on legal documents; and a statute recognizing civil union or marriage equality. Although the event was widely reported, laws guaranteeing equality would not be enacted for another decade.

Inspired by the belief that all of us belong to the same human community, Jáuregui never stopped advocating for equal rights. At the time of his death in 1998, he was campaigning to add a clause to the Constitution of the City of Buenos Aires that prohibited discrimination based upon sexual orientation. A week later, the Statutory Assembly unanimously approved a statement of principle that declared simply, “Todas las personas tienen idéntica dignidad y son iguales ante la ley.” (“All people have identical dignity and are equal before the law.”)

Jáuregui did not live to see the world he envisioned become a reality, but because of his leadership, strategy of visibility, and pride and his example, Argentina is now among the most advanced countries in the world to guarantee human rights for LGBT people. Same-sex couples may legally marry and adopt children together. Conversion therapy is banned. Gender diversity is recognized and citizens may change their name and gender on their birth certificates and identity cards through a simple administrative procedure. Sex reassignment surgery and hormone therapy are available through their public or private health care plans.

This year, President Alberto Fernández, whose son is a student and popular drag performer (and who used a rainbow flag as a pocket square at his father’s inauguration), signed a decree adding “Category X” to national identity documents and passports for non-binary, intersex, gender neutral, and gender non-conforming persons. (The U.S. issued its first passport with a “Category X” last month.) “There are other identities besides that of man and woman, and they must be respected,” Fernández explained. Jáuregui would have wept with joy.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on November 4, 2021

Recent Comments