By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

Everyone knew Charley Parkhurst. For some 15 years he was one of the most accomplished, fearless and celebrated stagecoach drivers in California. Described as having a “stout, compact figure, sun browned skin and beardless face with bluish-gray eyes,” he was “the boss of the road” on the routes from Sacramento to Placerville, Oakland to San Jose and San Juan Bautista to Santa Cruz. Social and generous, he was “never intemperate, immoral or reckless.” Not until his death did anybody know that “Cockeyed Charley” had been born female.

The discovery stunned all who learned of it. In Charley’s obituary in 1879, the San Francisco Call wrote, “The discoveries of the successful concealment for protracted periods of the female sex under the disguise of the masculine are not infrequent,” itself a revelation to modern readers. However, the paper, with a large whiff of disdain, added, “That she should achieve distinction in an occupation above all professions calling for the best physical qualities of nerve, courage, coolness and endurance … seems almost fabulous.”

Of course, Charley never would have been hired by a stage line as a woman, but after retiring as a driver, working as a logger, farmer and rancher, the state’s “crack whip” continued to live as a man. He even registered to vote in 1868, more than 50 years before women’s suffrage was granted by the 19th amendment. He may have been the first anatomically female citizen to cast a ballot in a presidential election in California.

Charley was hardly alone. During the Gold Rush and after, so numerous were the women who sought jobs dressed as men that businesses made it clear, “No young woman in disguise need apply.” How many of them were simply looking for work, or for financial or personal independence, and how many were also trying to express their authentic identity will never be known.

Opportunities for women who wished for, or had to, work were extremely limited. They could support themselves as washerwomen, servants, milliners, seamstresses, and, in some cases, factory workers. They also might find employment as a teacher or governess, but very few had enough education to qualify. Clerkships in stores and offices went to men almost exclusively.

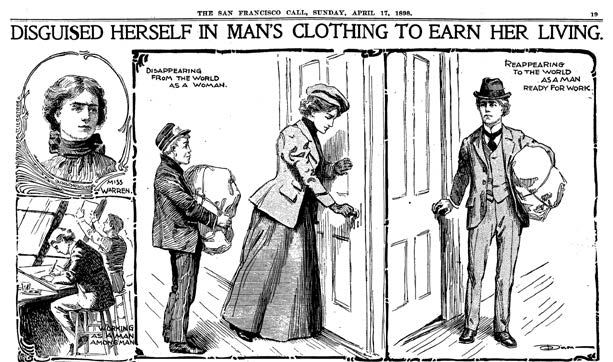

Despite the admonition, determined women in California continued to seek work dressed as men for many years, including John Warren. He knew that a female would not be hired for his job at Fowzer’s Photograph Gallery on Market Street, where he was employed as a re-toucher in 1898, so he “adopted male attire to win a position for herself.”

Warren “worked among men daily for months without any one suspecting her sex” until “the demon drink” ended his career. Asked one evening to the theater by three co-workers, a libation “to refresh the inner man” made her ill. She immediately “resolved that my disguise would have to be dropped.” She confessed to her employer the next day, who surprisingly allowed her to continue working there, now as a woman, showing each and all that women could do “men’s work.”

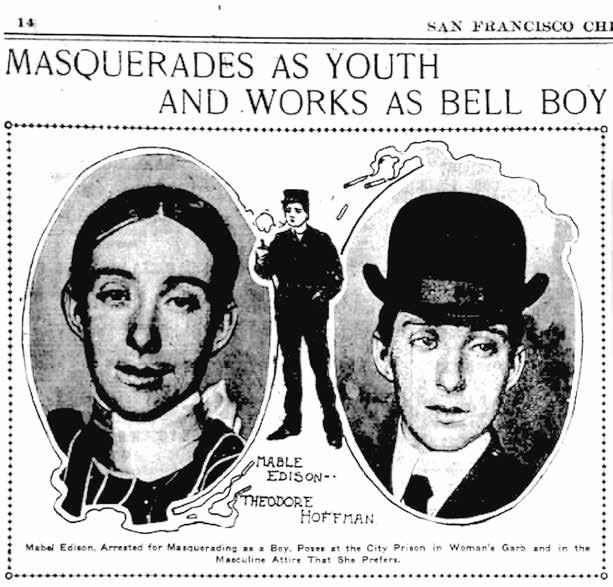

Unlike John Warren, San Franciscan Mabel Edison stated, “I always have wanted to be a boy,” when she was found out in 1902. “I can remember my mother telling me that when I was a year and a half old I always wanted to wear my little brother’s clothes. The wish has never left me.” Her health, she said, “is better when I am in—the other attire.”

Changing her appearance was the easiest part of her transformation. “I got a suit of boy’s clothes and took them to my room. Then I went to a hairdresser’s and had my hair cut short. I went back to my room, changed my clothes and walked out.” Finished with her old gender identify, she left her dresses in her old room. “I never went back for them,” she said.

Now Herbert Hoffman, she travelled from San Francisco to Los Angeles to find work in a hotel, which she did easily. “She was a very bright bell boy,” one of her employers said later. She seemed to know the business thoroughly and was quite smart. She was one of the smartest boys we ever had.” No one ever suspected she was “masquerading,” although “she had some ways that were rather effeminate.”

After a month in Los Angeles, Herbert returned to San Francisco. “I beat my way up on a freight train on the brake beams,” an extremely dangerous way to travel. The day she arrived she was hired as a bell boy at the California Hotel, but soon went to the Langham, where she worked for the next two months as Theodore Hoffman.

Eventually she was found out. Someone recognized her while lunching at the Third Street restaurant where she worked in female clothes before leaving for Los Angeles. He notified the police, who brought her to the Hall of Justice, where she confessed.

Mabel/Herbert/Theodore was open about her past. Before her time in Los Angeles, she worked in San Francisco as a girl. She was less open about her future. Asked, “Will you go back to the other dress when you have a chance?” she answered, “That remains to be decided.” Probably we will never discover whether she or he did or did not.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments