By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

By John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney–

On Tuesday, October 8, the U.S. Supreme Court will hold oral arguments in pivotal cases addressing whether discrimination against LGBT people constitutes unlawful sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Title VII prohibits an employer from firing or otherwise treating adversely “any individual because of such individual’s … sex.” Long established Supreme Court precedent makes clear that an employer’s actions occurred “because of” an individual’s sex if the employer would not have so treated the individual “but for” their sex.

Our community’s arguments are straightforward. With respect to sexual orientation, if an employer fires a lesbian or bisexual woman because she is attracted to another woman, but would not have fired her if she were a man attracted to the same woman, the employer fired her because of her sex, plain and simple. The same would hold true for a gay or bisexual man attracted to another man. “But for” the LGB person’s sex, the employer would not have fired them.

With respect to gender identity, if a transgender woman, such as plaintiff Aimee Stephens, had been born anatomically female and lived openly as a woman, she would not have been fired. However, because Stephens was born anatomically male and now lives openly as a woman, she was fired. “But for” her anatomical sex at birth, Stephens would not have been fired.

Stephens analogizes her case to religious discrimination. Just as “firing an employee for intending to change her religion is religious discrimination” outlawed by Title VII, so too firing an employee because she sought “to change her sex is sex discrimination,” prohibited by the Act.

The Supreme Court has also recognized that an employer’s taking adverse actions against an employee because the individual diverges from sex stereotypes or generalizations about how the different sexes should look or act is unlawful sex discrimination under the Act. As Stephens explains, “even ‘unquestionably true’ generalizations about women and men as classes cannot be used to discriminate against ‘individuals.’”

With respect to sexual orientation, the assumption that men are romantically and sexually attracted only to women and women only to men is an entrenched sex stereotype and generalization. An employer who fires an LGB individual because they fail to meet this expectation violates Title VII. Even though the majority of men and women are attracted to people of a different sex, Title VII prohibits an employer from discriminating against an LGB individual when they are not.

The Supreme Court has held that an employer’s discriminating against an individual because they date or marry someone of a different race violates Title VII. So too, an employer violates Title VII when it discriminates against an individual who dates or marries someone of the same sex. Indeed, if Title VII were not so interpreted, an LGB individual could exercise their constitutional right to marry a person of the same sex on Saturday, and their employer could fire them Monday morning for exercising that right, instead of marrying someone of a different sex. It’s sex discrimination plain and simple.

Regarding gender identity, the stereotype and generalization that people “throughout their entire lives” will “identify, appear, and behave in ways seen as typical” of their anatomical sex at birth is one of the most pernicious stereotypes in American life. Although this generalization is true for many people, an employer who discriminates against a transgender person for failing to conform to this sex stereotype violates Title VII.

Opponents contend that Title VII does not forbid an employer from discriminating against LGBT people as long as it discriminates against both male and female LGBT people. They assert that only when an employer, for example, fires male LGBT people, but not female LGBT people (what plaintiffs term “double discrimination”), does it engage in sex discrimination. Firing them all is not sex discrimination.

Ridiculous as this argument may seem, the key legal reason that the opponent’s argument fails is because Title VII protects every individual employee against discrimination based on their sex, and does not require an employee to make a group claim. As plaintiff Stephens explains: “An employer who discriminates against a female employee because of her sex cannot insulate itself from liability by also discriminating against a male employee because of his sex … . Two wrongs do not make a right.”

Similarly, an employer who, for example, fired an employee for converting from Christianity to Judaism could not justify such firing by claiming that it would fire any employee who converted from one religion to another. The argument is nonsensical.

The opponents also argue that Congress did not envision Title VII applying to anti-LGBT discrimination back in 1964 when it passed the Civil Rights Act. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has established unequivocally that when a statute’s plain text is clear—as is Title VII’s proscription of any form of sex discrimination—the Court should simply follow the plain words of the statute and not look into the subjective expectations of the legislators who enacted it.

Indeed, the Court has repeatedly held that sexual harassment, including same-sex sexual harassment, violates Title VII—something that seems obvious today, but that members of Congress would never have imagined when they passed the law 55 years ago.

Opponents also claim that the myriad efforts to include sexual orientation and gender identity explicitly in Title VII show that Title VII does not encompass such discrimination now. But nothing about these efforts means that LGBT discrimination isn’t also sex discrimination prohibited by current law. Congress has never enacted legislation to exclude discrimination against LGBT people from sex discrimination that Title VII prohibits.

Opponents also throw up red herring arguments about workplace dress codes and, of course, bathrooms, but these distractions are irrelevant to the critical issue of workplace discrimination against LGBT individuals that is before the Court.

We’ll be paying close attention next Tuesday and will share our impressions in the next edition.

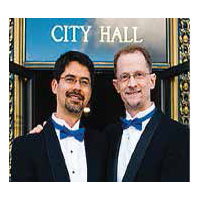

John Lewis and Stuart Gaffney, together for over three decades, were plaintiffs in the California case for equal marriage rights decided by the California Supreme Court in 2008. Their leadership in the grassroots organization Marriage Equality USA contributed in 2015 to making same-sex marriage legal nationwide.

Recent Comments