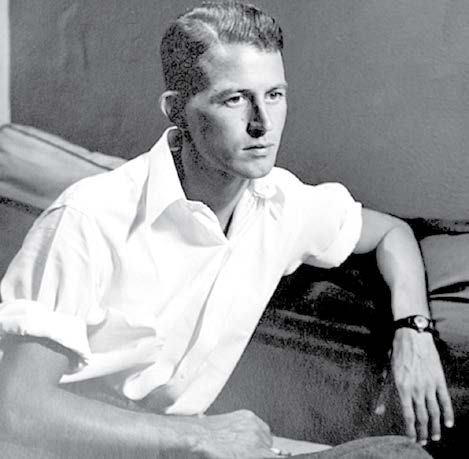

Truman Capote thought him “the single most charming-looking person I’ve ever seen.” To Gore Vidal, he was “un homme fatal.” Nightclub singer Jimmie Daniels called him “about the most beautiful boy anybody had ever seen.” For Christopher Isherwood, he was “the most expensive male prostitute in the world.” True or not, Denham Fouts became legendary as “the best-kept boy in the world,” one of the 20th century’s most famous grand horizontals.

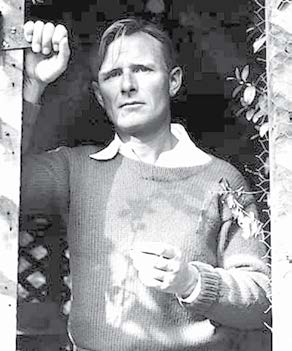

Isherwood met Fouts in 1940. Although he once told him, “You’re a rather vulgar little not-so-young boy from the most unpleasant state in the Union, whose chief claim to sophistication is having been thrown out of a few European hotels,” he also noted Denny’s allure. “He really understood how to give pleasure,” Isherwood wrote, “to make daily life more decorative and to create enjoyment of small occasions.”

Born into a middle-class family in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1914, Fouts left his job as bagger at a General Foods store to move to New York, determined to be kept. With “an instant and potent power of attraction,” as author Glenway Wescott described him, his became a world of admirers who understood that the pleasure of his company was expensive. He never “rented by the hour,” but like Blanche DuBois, Cafe Society’s favorite toy friend “always relied on the kindness of strangers.”

Not everyone was as enamored of him as actor Jean Marais or the 2nd Viscount Treadgear or Crown Prince (later King) Paul of Greece. Writer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau described Fouts “as a bad influence.” Photographer Cecil Beaton, in one of the sourest grapes since Aesop invented the fable, called him a “strumpet.” This perhaps because Beaton was deeply in love with Peter Watson—“My dearest Darling”—who became Denny’s greatest benefactor and longest inamorato.

One of Britain’s richest men, Watson could well afford to keep Fouts in the style and comfort his favors required. Because both men were “essentially made for honeymoons and not for marriages,” as poet Stephen Spender wrote later, their relationship was difficult and complicated. The bond between them, however, was real. Arguing and reconciling, living together and living apart, taking on different lovers and leaving them, Watson supported Denny for the rest of his life.

Unlike Denny Fouts, Jack Saul was a true rent boy. He was born into desperate poverty in Dublin in 1857 and was a “pretty boy” whose “person was blessed by nature in every capacity.” He was quick to tell prospective clients that he was “ready for a lark with a free gentleman at any time,” whether working in the notorious Monto district of Dublin, in Piccadilly or the Haymarket in London, or in the male brothels of both cities.

Unlike Denny Fouts, Jack Saul was a true rent boy. He was born into desperate poverty in Dublin in 1857 and was a “pretty boy” whose “person was blessed by nature in every capacity.” He was quick to tell prospective clients that he was “ready for a lark with a free gentleman at any time,” whether working in the notorious Monto district of Dublin, in Piccadilly or the Haymarket in London, or in the male brothels of both cities.

Saul became London’s most famous male prostitute, first as the author—or at least the source—of The Sins of the Cities of the Plain; or, The Recollections of a Mary-Ann—one of the earliest entirely homosexual pornographic novels written in English. It was published under his name in 1881. Victorian bookseller Charles Hirsch, who sold expensive erotica under the counter, claimed Oscar Wilde purchased a copy from him in 1890.

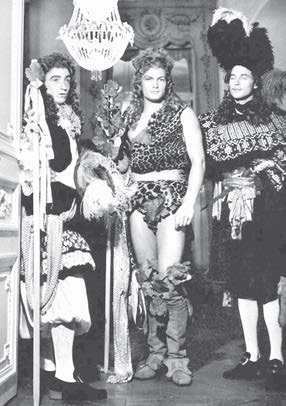

Jack’s renown also came from his testimony in the infamous Cleveland Street case of 1889, one of Britain’s most formidable same-sex scandals. No. 19 Cleveland Street was no ordinary brothel. It had class. There were Dresden vases on the mantlepiece, oil paintings on the walls and silk sheets on the beds. It catered to gentlemen of social position who faced possible prison time and certain social ostracism, should their sexual passions become public knowledge.

Unless someone complained, same-sex intimacy during the nineteenth century, however distasteful to the guardians of other people’s morality, was largely ignored. Called to the stand during the scandal, Jack was asked, “And were you hunted out by the police?” “No,” he testified, “they have never interfered. They have always been kind to me.” “Do you mean they have deliberately shut their eyes to your infamous practices?” “They have had to shut their eyes to more than me.”

That admission was scandalous in itself, but what truly shocked rigidly class-divided Victorians about Cleveland Street was someone from one class consorting somebody from another, blue bloods “being thick” with rent boys. By the end of the trial, 22 men, mostly from the upper classes, had fled the country. Jack, himself never prosecuted for his admitted crimes, took a job in service at a small, presumed reputable hotel. He returned to Dublin a few years later, where he died in 1904.

That admission was scandalous in itself, but what truly shocked rigidly class-divided Victorians about Cleveland Street was someone from one class consorting somebody from another, blue bloods “being thick” with rent boys. By the end of the trial, 22 men, mostly from the upper classes, had fled the country. Jack, himself never prosecuted for his admitted crimes, took a job in service at a small, presumed reputable hotel. He returned to Dublin a few years later, where he died in 1904.

Other male sex workers achieved lasting fame, Phaedo of Elis and Febo di Poggio among them. Denny and Jack, however, became legendary. Fouts especially, “absolutely enchanting and ridiculously good-looking,” inspired a generation of writers. Capote’s “Unspoiled Monsters,” a chapter in Answered Prayers, his unfinished last novel; Vidal’s short story “Pages from an Abandoned Journal;” and Isherwood’s novella “Paul,” included in Down There on a Visit, are about him. No other kept boy became the literary muse to so many creative minds.

Wilde alluded to the Cleveland Street scandal in The Picture of Dorian Gray, a book that one contemporary reviewer called suitable for “none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys,” the very people caught up in the scandal. Remembered now for more than 100 years, most recently Saul inspired The Sins of Jack Saul—The Musical, staged in London in 2016. For many, Jack is now the “patron saint of rent boys the world over.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Recent Comments