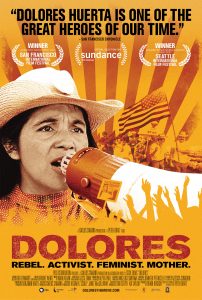

San Francisco native Peter Bratt’s inspiring documentary Dolores opens in the Bay Area this weekend. The film recounts the life and work of Dolores Huerta, who is described as “the most vocal activist you’ve never heard of.” She has largely been “written out of history.” Bratt’s compelling film is a necessary corrective.

Huerta was instrumental in organizing California farm workers with Cesar Chavez, fighting injustice and discrimination, as well as coordinating efforts to fight pesticide use on farms. She also organized the Delano grape strike and boycott of grape growers in California from 1965–1970.

Huerta had 11 children (with 3 husbands). Her activism often took her away from her family, but she instilled her values of ethnic pride on her sons and daughters, and they rallied around her when she was horribly bashed by San Francisco police officers at a peaceful demonstration outside the St. Francis hotel where George H.W. Bush was campaigning for president.

Dolores features interviews with Huerta—still as feisty as ever at 87—and her children, as well as Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis, and LGBT activist Rick Rivas, among others.

Bratt spoke with the San Francisco Bay Times about his film and its subject.

Gary M. Kramer: Where did you first learn about Dolores Huerta, and what prompted you to make a film about her life and work?

Peter Bratt: I was born and raised in San Francisco by a single mom in the Mission district. My mom was involved with the farm workers union, so I was aware of Dolores as a child. I always had a great amount of respect for her, but it wasn’t until Carlos Santana called and put a stake in the ground to make the film. I knew about her, but I didn’t know the depths of her work until I did the research and made the film.

Gary M. Kramer: Why do you think people don’t know more about her?

Peter Bratt: I feel that she was threatening because she challenged patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism. She fought for workers to share the fruits of their labor, for workers to be equal, and she confronts racial injustice. This is why she is seen as a threat.

Gary M. Kramer: In all of your films, you focus on inspirational stories about marginalized characters. Can you discuss your affinity for telling these stories?

Peter Bratt: I feel like it’s not a reach for me to train the lens on these issues. There are Latino families—fathers and mothers—struggling to accept their children’s sexuality, like in La Mission, and they intersect with race and class. In Dolores’ case, she’s fighting for labor justice, which is a racial issue, too. She’s a woman working in a male domain, and that has her running into other issues. She bumps into environmental issues, with pesticides. If you stay true to people’s authentic experiences, you can’t help but explore those issues, which people tend to silo. Those intersections and conflicts come up organically. I thought I was going to chronicle Dolores’ fight for labor justice, and then I found her political evolution, which cross-pollinated with other issues.

Gary M. Kramer: Can you talk about how you assembled the film clips, photographs, and archival footage to tell Dolores’ story?

Peter Bratt: It was a deliberate choice not to use a narrator to tell the story. It was a challenge to let the archival footage and the interviewees tell the story. I needed images to bridge the gap between two points. We found seven decades of footage. We had to show her doing the work in the fields, rather than telling it. Viewers had to witness her struggle.

Gary M. Kramer: What can you say about getting the interviews with Dolores and her children, as well as with Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis and others?

Peter Bratt: In activist and organizer circles, Dolores is well known and is a legend, so doing a film on Dolores opened doors to Angela Davis and Gloria Steinem. That speaks to the respect she has in many people’s eyes. Dolores told me the other day that she inspired Gloria and Angela, and vice versa.

Gary M. Kramer: You tell Dolores’ story in an evenhanded fashion. Dolores is not a hagiography. Can you talk about your approach?

Gary M. Kramer: You tell Dolores’ story in an evenhanded fashion. Dolores is not a hagiography. Can you talk about your approach?

Peter Bratt: For me, it was having this archival material and letting that speak for itself. Dolores doesn’t censor herself. She and her children had no filters. They were organic and authentic—this is how I am, take it for better or worse. The one challenge I had—and she resisted, and I found this in Gloria and Angela too—is that there’s an awkwardness about this film being about her. She wanted to talk about organizing and movement building. She couldn’t understand why I was digging for the personal and interviewing the entire family She thought I’d miss the bigger picture, but that’s the activist trained on moving the cause forward. I interviewed her off and on for nearly three years. After time, there was a well-established trust. The depth of her work is mind-boggling.

Gary M. Kramer: Were there ever moments when she directed you?

Peter Bratt: No. I had to stand my ground and reassure her that people will see the bigger picture through her narrative and identifying through her.

Gary M. Kramer: How did Dolores inspire you?

Peter Bratt: For me, what I took away—discouraged as I am by the current political climate, and thinking “What’s the use?”—was after interviewing the people around her, and seeing her still organizing, she convinces them they still have power, and that helps create change. She speaks truth to power no matter who you are and where she is. That frustrates people or pisses them off. I don’t think she apologizes. I like that. We need more of that. She gave me emotional fortitude that re-invigorated me. I hope others get that from the film, especially now.

© 2017 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Recent Comments