By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

“The cause of woman took an immense stride forward last night,” The Morning Telegraph stated in its review of Der Wald,performed for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera House on March 11, 1903. Praising Ethel Smyth (1857–1944), its composer, the New York City newspaper shared, “This little woman writes music with a masculine hand and has a sound and logical brain, such as is supposed to be the special gift of the rougher sex. There is not a weak or effeminate note in Der Wald.”

Other New York critics maligned the new opera for exactly the same reason. “Her work,” the New York World complained, “is utterly unfeminine.” Worse, she simply was not qualified to write about “the battle of lust with holy love for the soul of a man.” “Woman with all her intuition cannot penetrate this corner of human experience. It is just the one thing in life she can never know, unless she ceases to be a woman.”

Smyth disagreed. She could be both a woman and composer.

Whatever the critics thought, the first opera written by a woman ever to be performed by the Metropolitan Opera—and the last the company presented for more than a century—was well received by “one of the largest and most brilliant audiences” of the season, who arrived, uncharacteristically, on time for the performance. At its conclusion, the applause “continued for ten or fifteen minutes, surpassing even the most generous for which the opera patrons are distinguished.”

Smyth may have been disappointed with the reviews, but she could not have been surprised they made an issue of her gender. Born in 1858 in Sidcup, an English village that is a suburb of London, she grew up in a world that regarded composition as “an unseemly area of practice for a woman.” A sweetly sentimental parlor song might have been acceptable, but chamber music, orchestral works, and certainly operas were for men to write. Defiantly, Smyth wrote them all.

“I feel that I must fight for [my music] because I want women to turn their minds to big and difficult jobs, not just to go on hugging the shore, afraid to put out to sea.” She well understood a certain amount of militancy would be necessary, urging female musicians and composers to “swear that unless women are given equal chances with men in the orchestra and unless women’s work features in your programs, you will make things very disagreeable indeed.”

Smyth knew who she was at an early age, writing privately to Henry Barrett Brewster in 1892, whose friendship, she admitted, was the most important of her life, that “it is so much easier for me, and I believe a great many English women, to love my own sex more passionately than yours.” She told the world the same thing in her memoir, Impressions That Remained, published in 1919: “My relations with certain women, all exceptional personalities I think, are shining threads in my life.”

Those “shining threads” included Lady Ponsonby (1832–1916), “women’s advancement” advocate; Irish writer Edith Somerville (1858–1949; and sewing machine heir and music patron Winaretta Singer, the Princesse de Polignac (1865–1943), who, according to Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), had “ravaged half the virgins in Paris.” Many years later she became infatuated with Woolf herself, who, feeling differently, said it was “like being caught by a giant crab.” They became good friends instead.

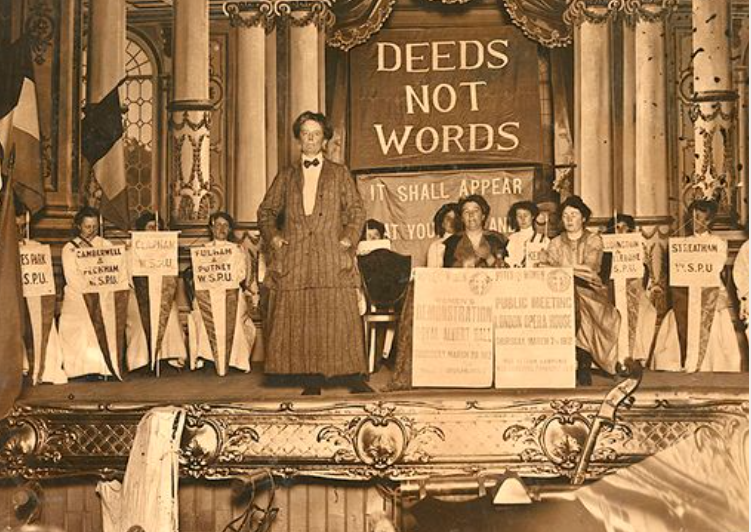

Smyth met Emmeline Pankhurst, a passionate feminist and leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a militant all-women’s activist group, in 1910. Immediately impressed and quickly infatuated with her, she described the experience as “the fiery inception of what was to become the deepest and closest of friendships.” Not only did Smyth become “an ardent suffragette,” but she also stepped away from music for the next two years so she could devote all her time to the cause.

Her greatest contribution to the suffrage movement may have been The March of the Women, which she composed in 1910 and dedicated to the WSPU. Pankhurst herself introduced it at a rally in London in January 1911, where she welcomed activists recently freed from prison “back to the fighting line.” With lyrics by Cicely Hamilton (1872–1952), The March, which expressed the suffragettes’ goal for true equality, became the anthem of their movement. It was performed at almost all of their events.

On March 4, 1912, Smyth was one of some 100 women arrested for smashing windows in London to bring attention to the suffrage cause. Her particular target was the home of the Colonial Secretary, retaliating for his very sexist remark that “if all women were as pretty and as wise as his own wife, [they] should have the vote tomorrow.” For her militancy, she was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison; Pankhurst was given the cell next to hers.

When conductor and great friend Thomas Beecham visited her in her incarceration, he witnessed a memorable, defiant performance of The March. “I arrived in the main courtyard … to find the noble company of martyrs marching round it and singing lustily their war-chant while the composer, beaming approbation from an overlooking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush.” Beecham concluded that Smyth, encouraged to reflect and repent while in prison, “neither reflected nor repented.”

Always fiercely independent, Woolf described her appearance as that of “the militant, working, professional woman—the woman who had shocked the country by jumping fences both of the field and of the drawing room, had written operas, was commonly called ‘quite mad,’ and had friends among the Empresses and the charwomen.” Were Smyth and Pankhurst intimate in every way? Woolf thought so, writing to her nephew Quentin Bell, “In strict confidence, Ethel used to love Emmeline—they shared a bed.”

Despite the controversy that swirled around her, Smyth was knighted a Commander of the British Empire in 1922, the first woman so honored for composition. She was well remembered. In his memorial broadcast on the centennial of her birth in 1958, Beecham called her “one of the most remarkable people of our time,” telling listeners that there were many “who cherish her memory, and we do so with admiration, respect, and a great deal of love.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on April 18, 2024

Recent Comments