By Kurt Bilse, RN, BSN, PHN–

Last year, like so many other Americans, I watched the hurricanes, fires and other natural disasters sweep across our country and wished that I could help in the aftermaths. As a registered nurse, I knew that my skills could be used. I made last minute calls to disaster aid agencies, only to get bogged down in unanswered voicemails and emails due to the fact that everyone was out working the field. I realized if I wanted to be of any help at the next disaster, I needed to do my research and get involved “now” rather than “later.” After a lot of research, I registered with the American Red Cross (ARC) and my local Medical Reserve Corps (MRC).

Kurt Bilse

While many people are familiar with the ARC, few know about their local and national MRC. As the Corps holds: “The need for the MRC became apparent after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when thousands of medical and public health professionals, eager to volunteer in support of emergency relief activities, found that there was no organized approach to channel their efforts. Local responders were already overwhelmed and did not have a way to identify and manage these spontaneous volunteers, and many highly skilled people were turned away. As a result, the MRC was established to provide a way to recruit, train and activate medical and health professionals to respond to community health needs, including disasters and other public health emergencies. MRC volunteers include medical and public health professionals, such as physicians, nurses, physician assistants, pharmacists, dentists, behavioral health professionals, veterinarians and epidemiologists. Many other community members also support the MRC, such as interpreters, chaplains, office workers and legal advisors.”

It is with the MRC that I was deployed to the Mendocino Fire Complex.

As I watched the Redding Fires progress on the evening news, I knew that the activation call would be coming soon, telling us to prepare to deploy. This would be my first deployment to a disaster event, so I was a bit apprehensive to receive the call. I was already awake at 4 am when the automated call came asking me for my availability and prompting me to prepare to deploy.

Within minutes I was packing my bag, checking electronics and gathering my medical equipment. Soon a text followed from our unit leader saying that we were going on standby to see how the Mendocino Fire Complex progressed and if we were going to be needed more locally. Within 24 hours, the fires around Clear Lake exploded and the communities around Lake County began to be evacuated one by one. I was deployed to Lower Lake High School, which served as one of the main shelters for the fire. As I drove in the dark through the Napa Valley and up into the hills, I could smell the smoke in the morning air become thicker and more pungent as I ascended.

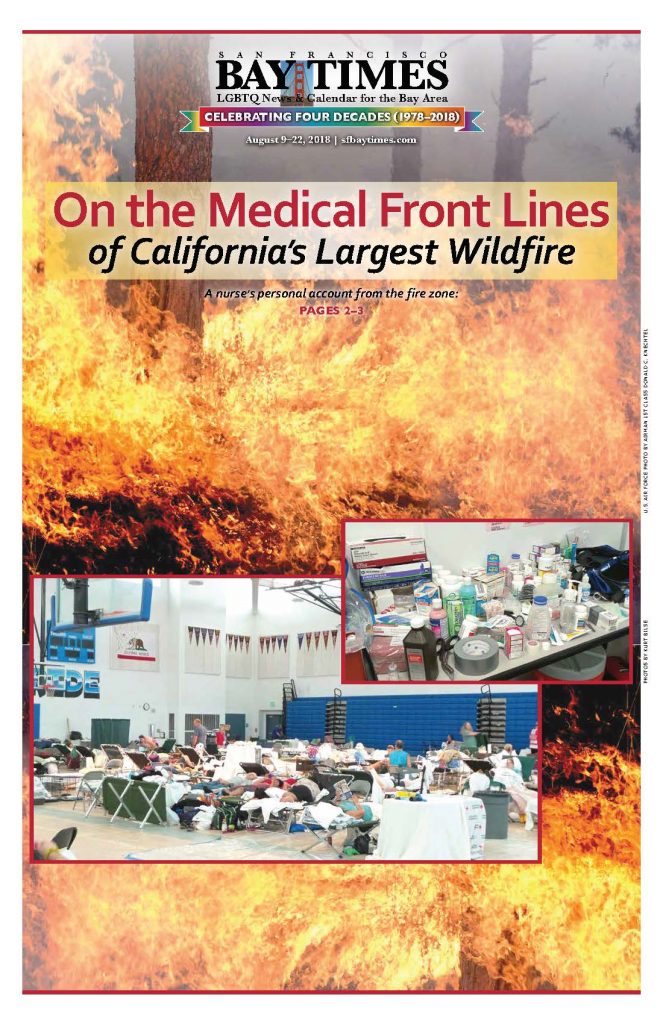

When I arrived at the campus, I saw tents covering the football field and lawns surrounding the classrooms. People walked through the campus as if in a stupor, waking their pets and trying to assess the events that had taken place. I walked in to the first of three gyms on the campus that was filled with a mass of people sleeping, or sitting, on cots. A look of bewilderment on those who were awake displayed the shock that they were still in from having to flee their homes so quickly. Eventually we would see all three gyms fill to approximately 450 people as communities around the lake were evacuated and then allowed to return in succession as the fire lines encircled the lake.

Over the following week we heard countless stories of evacuation notices, police banging on doors, people having less than five minutes to grab pets, purses, wallets and shoes, and fleeing for their lives. Then followed the confusion of getting to safety: figuring out where to go, where to stay, how to get there and more. Those who did not have family or friends to stay with out of the area ended up at one of the ARC shelters. They were greeted with a cot, blankets, a meal and a pack of necessities including toiletries. The students and parents of Lower Lake High School were busy preparing breakfast for the evacuees (whom we often refer to as “clients”) and numerous ARC volunteers continued to register people, set up cots, feed, clothe, direct, comfort and fulfill a plethora of clients’ needs.

The MRC set up a medical station in an office off one of the gyms. Our first task was to set up emergency medical supplies, first aid equipment and a myriad of over-the-counter drugs. Soon people were waking up and realizing the impact of their quick exodus from their homes. One of the first realizations was that they left their medications at home and/or did not have sufficient refills to get them through their stay at the shelter. Few of the clients that we saw from the fires had a list of their medications and/or had saved any information in “the cloud” and could not remember the names and doses of their prescriptions.

Many residents of the area used independent pharmacies (rather than chain stores) that were now closed and evacuated along with their employees. Also, many of their doctors and their medical offices were closed and evacuated. This is a common occurrence in a disaster. As a result, MRC nurses and local pharmacies are allowed emergency powers to case manage, order and provide emergency dosing of prescriptions for a 3–5-day supply. The task is much more complicated than one would assume. Many clients were still in PTSD and had great difficulty remembering names of drugs, doses, and scheduling. Many were on public assistance and we had to arrange payments for some meds. Several did not have transportation and we had to arrange delivery and dispensing, once their meds arrived at the shelter.

A majority of the clients at the shelter were elderly or the disabled, and several were dependent on in-home caregivers to administer their medications and to assist in their activities of daily living, such as toileting, eating, dressing, getting in and out of bed or a chair, etc. When the resident is forced to evacuate, so is the caregiver. In most cases, the caregivers themselves were forced to evacuate to a family member’s or friend’s home outside of the region, thus leaving the clients at the shelter with little help. While stretched to their limits, the Red Cross nurses and volunteers filled in this gap and did a remarkable job.

As the days progressed, we saw waves of people come and go as communities evacuated. Empty registration lobbies swelled with dozens of evacuees within minutes. As they filtered in, we bandaged multiple cuts, scrapes and blisters. We administered breathing treatments via a nebulizer for asthmatics and COPD patients. We held hands and comforted during anxiety attacks. We searched pharmacies for special infant formulas for newborns. We rushed juice and candy to diabetics who were hypoglycemic. We identified clients with behavioral health issues and/or the chemically dependent and addressed their issues by getting them their medications, meeting with our staff of professionals, or transporting them to facilities that could provide better assistance.

As the days progressed, we saw waves of people come and go as communities evacuated. Empty registration lobbies swelled with dozens of evacuees within minutes. As they filtered in, we bandaged multiple cuts, scrapes and blisters. We administered breathing treatments via a nebulizer for asthmatics and COPD patients. We held hands and comforted during anxiety attacks. We searched pharmacies for special infant formulas for newborns. We rushed juice and candy to diabetics who were hypoglycemic. We identified clients with behavioral health issues and/or the chemically dependent and addressed their issues by getting them their medications, meeting with our staff of professionals, or transporting them to facilities that could provide better assistance.

Several calls to 911 were made for seizures, chest pains and other critical issues that required medical attention that we were not equipped to handle. We also provided education to clients about their medications, health issues, diseases and resources that they could use during the evacuation and once they returned home.

The fires progressed so fast that we had to remain adaptable at all times. On my first day at the shelter, we sent a team to a newly opened shelter in Kelseyville. Within an hour of arriving at the shelter, an evacuation order was given for the town and the shelter. The team had to assist with the evacuation of the shelter and get them resettled at the Middletown shelter. As the nights progressed, we became experts in smelling smoke and assessing if the fires were progressing or regressing from our area.

One night, after a 15-hour shift, my team lead and I had just finished eating dinner when she received a call from our command. We were warned that the winds and the fire had suddenly changed and were heading to the city of Clear Lake. We were to be prepared for a highly probable call later in the evening for orders to evacuate the town and the shelter. I watched as a look of alarm flushed across her face as the complexity of evacuating hundreds of people, animals and a medical unit (via buses and ambulances) ran through her head.

We went to bed that night not knowing what the following hours would bring, hoping we could steal enough sleep to be functional once the call came. As the night progressed, I would open my eyes, check my phone log to make sure that I hadn’t missed “the call,” sniff the air to assess the smoke and direction of the fire, and drift back off to sleep. In what seemed like merely 15 minutes, my 5 am alarm was sounding, waking me for my day shift. I smelled the air and looked up to see blue sky. Overnight prayers were answered, winds shifted and the fire changed direction once again. We proceeded to head down to the shelter for our usual shift.

As the day progressed, smaller communities around the lake were evacuated. In the late afternoon, though, the evacuation orders for the largest community of the north shore, Lakeport, were removed, and the majority of the evacuees in our shelter returned home. By the end of my shift, the shelter seemed empty in comparison. I was able to return home that evening.

As an oncology nurse, I am accustomed to working with patients who have suddenly had to deal with life-changing events. The newly discovered lump, the positive test result, or the doctor’s office visit confirming a diagnosis can bring turmoil to the soul and change a life in an instance. In almost all circumstances, however, there is always home to retreat to from the storm: home to retreat, home to regroup, home to shelter and hide away from the world and its problems at least for a moment.

The innate need for a sense of home is one of the basic foundations we each use to cope with life’s greatest struggles to accomplishing even the most mundane tasks. This past week I’ve been immersed in a sea of people caught in the frustration of not being able to return home and the fear of losing that home to fire. I’ve had to perform major nursing interventions like administer CPR and assist an epileptic during a seizure while calling 911.

It’s the little tasks, though, that can be the most satisfying at the shelters, like helping an elderly lady open a pill bottle because she was too stressed and confused from evacuation to twist the lid, rubbing the back of someone listening to fire updates and hearing spot fires are sighted on the ridge above their house, walking a caged pet because the owner can’t, and holding a crying child because her mom is too exhausted and needs a quick respite.

As we have seen all too often this past year, home and all of the tangible and intangible security it provides can disappear in a matter of minutes. While we live in one of the most affluent countries in the world, our social safety net is fragile and has gaping holes in it. The events in the past year have often shown the devastating results of when that safety net fails. It is dependent on neighbors caring for neighbors in the direst of times to hold it up.

You, the reader, have skills your community needs. Don’t wait until the next disaster hits before you act. Research the available organizations and take a step to get involved today! You will meet some of the nicest, giving people you will ever meet along the way.

As of this writing, the rest of our local MRC team is returning to their homes and another county’s MRC is coming to assume the medical responsibilities at the shelter. We will be busy restocking our emergency response bags, the oxygen tanks and medical supplies so that we are ready for the next crisis. No one looks forward to another disaster, but I can’t wait to meet up again with the fantastic people I’ve met and worked with at my local MRC!

Kurt Bilse is a Bay Area-based registered nurse specializing in oncology. Before volunteering with the American Red Cross and the Medical Reserve Corps, he provided medical services to underserved communities in Nicaragua with the non-profit humanitarian organization Global Medical Training.

The Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) is a national network of volunteers, organized locally to improve the health and safety of their communities. The MRC network comprises approximately 190,000 volunteers in 900 community-based units located throughout the U.S. and its territories.

MRC volunteers include medical and public health professionals, as well as other community members without healthcare backgrounds. MRC units engage these volunteers to strengthen public health, improve emergency response capabilities and build community resiliency. They prepare for and respond to natural disasters, such as wildfires, hurricanes, tornados, blizzards and floods, as well as other emergencies affecting public health, such as disease outbreaks. They frequently contribute to community health activities that promote healthy habits.

Examples of activities that MRC volunteers participate in and support include emergency preparedness and response trainings, emergency sheltering, responder rehab, disaster medical support, disaster risk reduction, medical facility surge capacity, first aid during large public gatherings, veterinary support and pet preparedness, health screenings, obesity reduction, vaccination clinics, outreach to underserved community members, heart health, tobacco cessation and much more.

For additional information: https://mrc.hhs.gov/HomePage

Prepare a “Go Bag” filled with emergency items that you will need. Store it in a closet near the door that you will likely use for your exit. Keep the following in mind as you put your “Go Bag” together:

Tailor it to the weather in your area.

Here in the Bay Area, we rarely need an ice scraper, but you might want a battery-powered fan. Add or subtract items from the list that you know you’ll need where you’re evacuating from.

Include items that suit your family.

If you have kids or pets, you can add things like diapers, dehydrated food, dog treats or a water bowl.

Water

It’s recommended to have one gallon of water per day per person or pet. You should keep at least three gallons each per person or pet at home. The shelter will have plenty of water, but have water to sustain you until you get to a shelter.

Food

You should have at least three days’ worth of food. Concentrate on non-perishable food that doesn’t require refrigeration or much prep and water. Consider cereal, ready-to-eat canned fruits (or canned veggies, juice and meat), or energy-rich snacks like trail mix and granola bars. Remember to have vitamins and special supplies around for anyone with special needs, such as pets, babies and the elderly.

Medication

Have some extra medication on hand for times when disaster strikes and you can’t leave your home to refill your prescription. Remember to also store over-the-counter medication like painkillers, antihistamines, calamine lotion, Alka-Seltzer, laxatives, anti-diarrhea medication, sterile eyewash and contact lenses (if you use them).

If you are dependent on medications, type out a list of them, the dose and how often you take them. Include the name and number of the prescribing doctor. Print this list and include it in your Go Bag. Then email it to yourself and/or a family member as a backup. Take a digital photo of the list and/or photograph the label of each of your medications. Email them to yourself and/or save them to “the cloud” so that you can access them from a computer in an emergency.

Make a list of the pharmacies (mail order or local) and your doctor’s contact information that you use and back them up as you would your medications.

If you are a diabetic, pack shelf stable juices, packed meals and hard candies in your Go Bag in the event you become hypoglycemic. Remember to evacuate with your meds and the necessary needles and testing equipment.

First Aid Kit

It should have latex gloves, gauze pads, a thermometer, sterile bandages, Band-Aids, petroleum jelly, salve for burns, antibiotic ointment, adhesive tape, towelettes, hand sanitizers, sunscreen, and instant cold packs. (The shelter may or may not have these.)

Tools and Supplies

This includes items such as candles, matches in a waterproof container, scissors, tweezers, a sewing kit, a flashlight, extra batteries, a small fire extinguisher, a manual can opener, a knife, a hand-crank or battery-operated radio (with batteries) and a wrench to turn off the gas and water. Be sure to also have a map of the area in case you need to look for a shelter.

Hygiene Products

Include toilet paper, feminine products and toiletries.

Cleaning Products

Consider packing garbage bags, dish soap, bleach and disinfectant.

Clothing

Rain gear, at least one outfit, work boots or durable sneakers, and thermal underwear should all be included.

Important Documents and Related Items

You should bring cash, your driver’s license, passport, social security card, family records, bank account numbers and a list of important and emergency phone numbers. Make sure you have a copy of your will, insurance policies, and other contracts and deeds.

Miscellaneous Items

These may include blankets, sleeping bags, paper cups, paper plates and plastic utensils.

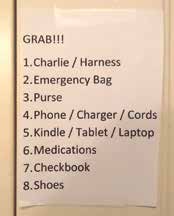

Remember that you are evacuating for a time period of 24 hours to two or more weeks. Consider the everyday items you use that you will need that aren’t stored in your Go Bag. These are the items often forgotten in the rush to evacuate. Think of the 7 to 10 most important items that you need to function and to remain sane in the shelter or hotel. Prioritize them and type them out in a list. Tape this list on the door frame of the door you will evacuate from or the closet you store your Go Bag in. This will be your final check list that you can quickly check before you flee to make sure you have everything. It might look something like this:

Assess Your Home Insurance (If Applicable), Research Hotels

Frequently, home insurance will pay for policy owners to stay in hotels while they are evacuated. Assess your policy to determine your coverage. If you have special needs like pets, ADA accessibility or the like, research what hotels in the area can accommodate your needs.

Hotels fill up instantly in a disaster and very, very long lines develop. Identify three or four hotels you would prefer to evacuate to and put their phone numbers or their app on your phone. As soon as you know that you are evacuating from your home and are in a safe location, call ahead and make a reservation for the room(s) you need. Do not wait until you arrive at the hotel, as rooms will probably already be gone. If rooms are already booked at most locations, look for casinos, conference centers and resorts outside of the immediate area.

1. If you or a loved one depends on a caregiver, you need to have a discussion about what the expectations are during an evacuation. Is the caregiver expected to follow the client to the shelter? To where will the caregiver evacuate?

2. If the caregiver does not go to the shelter, disaster agencies will attempt to assist evacuees once they are settled into a cot. It is not guaranteed that they will have the manpower, resources or expertise to provide the same level of care that an in-home caregiver can provide.

3. Family or friends should be prepared to assist the evacuee at the shelter and/or host them in their own homes. In preparation to do this, family members should assess equipment needs, like renting hospital beds, commodes, lifts, etc., and locate providers in their area prior to a disaster event.

4. The American Red Cross (ARC) provides flat, very firm cots. If medically necessary, they can provide head and leg tilting cots with a thin pad. If you anticipate joint, back or general discomfort sleeping on cots, consider adding cushions, pillows or pads to your emergency bags to bring to the shelter.

5. Shelters will generally have first-aid supplies. If the Medical Reserve Corps is present, they will have a limited number of over-the-counter drugs like aspirin, Tylenol, anti-diarrhea meds and the sort. They will not stock prescription medications or painkillers, and are not allowed to administer them. Nurses on the team will be able to authorize emergency refills of non-controlled drugs once the governor declares an emergency. If a medical doctor is onsite with the team, he will be able to authorize emergency prescriptions of controlled medications as needed.

6. If you have a pet, it is advisable to store a collapsible pet cage along with a blanket and bowls in your car trunk if you are able. ARC will provide these items, but in the first hours and days of the crisis, they may be limited. Many pets are brought to the shelters and it is very stressful for them. It is much easier on them if they are caged and comfortable.

7. Usually there are grounds around a shelter and you are allowed to stay in your own tent if you have one. Consider including one if you are claustrophobic or feel stressed in large crowds.

8. If you are chemically dependent or on psychiatric medication, the middle of a disaster is not the time to quit cold turkey.

9. If you are chemically dependent, now is the time to deal with it instead of finding yourself in withdrawals in the middle of a disaster. If you find yourself as an evacuee and separated from your source, find a medical volunteer as soon as you are registered at the shelter. The volunteer will be able to assist you in seeking appropriate medical and/or social attention before a crisis occurs.

10. If you have psychiatric or behavioral health issues, the shelters usually have trained staff available to help in getting you medical or county service assistance.

Recent Comments