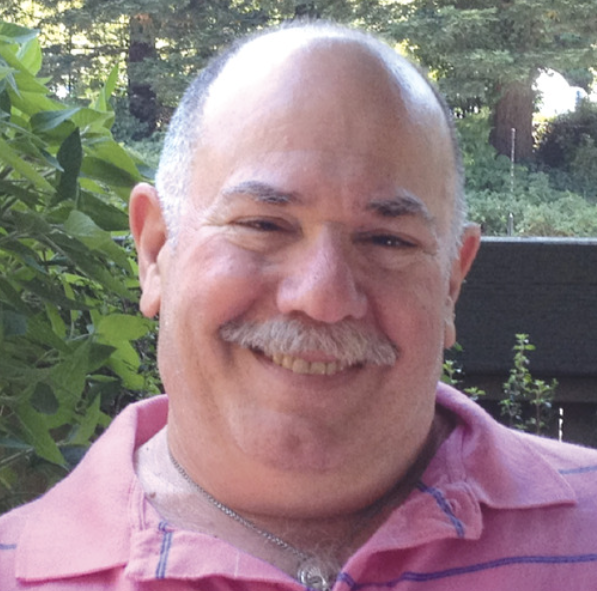

By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

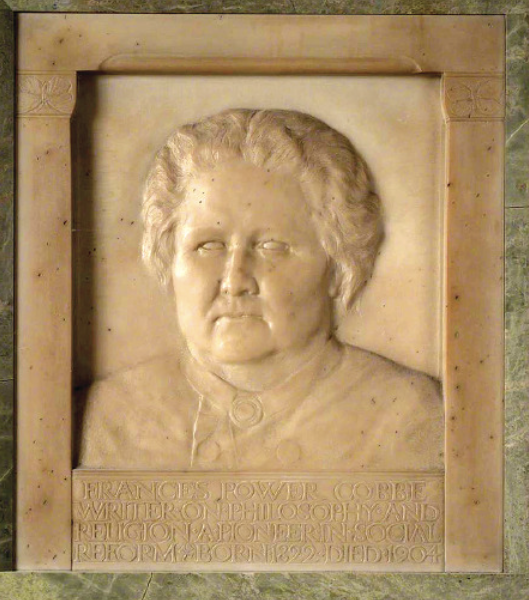

Dignitaries from all over the world celebrated Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904) on her eightieth birthday for her lifetime of great works. “We, who recognize the strenuous philanthropic activity and the high moral purpose of your long life,” they proclaimed, “wish to offer you this congratulatory address as an expression of sincere regard.” Working to save children from the horrors of the workhouse, to free battered women from abusive marriages, and to rescue animals from needless cruelties, she campaigned tirelessly for social change.

Cobbe was consistently forceful when writing about “women’s concerns,” including their right to vote, to receive a university education, own property, and leave an abusive marriage. She was born into a prominent Irish family near Dublin, and explained that “a married woman’s inheritance and even her own earnings (if she could make any), were legally robbed from her by her husband,” who having “beaten and wronged his wife in every possible way could yet force her by law to live with him and become the mother of his children.”

With divorce then especially difficult to get, Cobbe demanded that Parliament change the marriage laws to at least protect women from domestic violence by their husbands. In her bluntly titled pamphlet Wife Torture in England (1878), she wrote, “The notion that a man’s wife is his PROPERTY in the sense in which a horse is his property, is the fatal root of incalculable evil and misery.” Only when women had the legal right to leave their abusive husbands, she believed, would they be safe.

Her advocacy led Parliament to pass the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1878. For the first time, women could file for a legal separation from their husbands, be granted custody of their children, and receive financial support, although it was rarely granted. Even so, Cobbe believed, “The part of my work for women … to which I look back with most satisfaction was that in which I labored to obtain protection for unhappy wives, beaten, mangled, mutilated, or trampled on by brutal husbands.”

Always their stalwart champion, Cobbe occasionally took women to task for causing their own troubles. “A great deal of the sickliness of women,” she wrote in her Autobiography (1894), “is undoubtedly due to wretched fashions of tight-lacing, and wearing long and heavy skirts, and tight, thin boots, which render free exercise of their limbs impossible.” Almost as bad was seeing “the adornments so many women use of dead birds, stuck on their empty heads and heartless breasts. These things are a disgrace to women.”

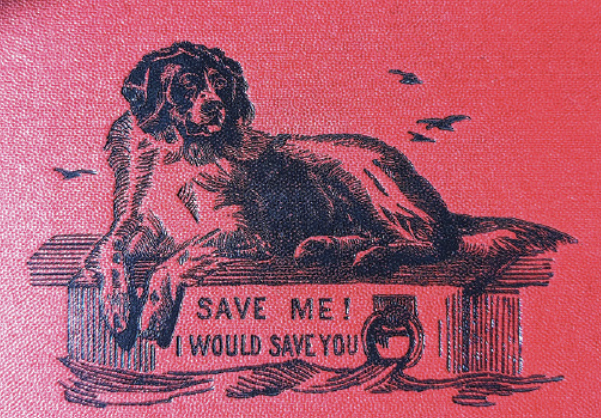

From the earliest days of her career, Cobbe advocated for the humane treatment of animals. Her first of many articles, “The Rights of Man and the Claims of Brutes,” which “I hoped might help to direct public attention to them,” appeared in Fraser’s Magazine in 1863. “So far as I know,” she wrote later, “it was the first effort made to deal with the moral questions involved in the torture of animals either for sake of scientific and therapeutic research, or for the acquirement of manipulative skill.”

Although “frequently described” by her critics as “a woman ‘who would sacrifice any number of men, women, and children, sooner than that a few rabbits should be inconvenienced,’” she persevered. Her work against the callous and unconcerned use of animals in scientific and other research led to the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876. It remained in force for 110 years, when it was replaced by the Animals Scientific Procedures Act of 1986, which currently regulates the use of animals in experiments in the United Kingdom.

Supporting Cobbe in all her advocacy was Welsh sculptor Mary Lloyd (1819–1896), her life partner for 34 years and whom she met when visiting Rome during the winter of 1861–62. Both were friends of famed American actor Charlotte Cushman (1816–1876). “One day,” she wrote in her autobiography, “Miss Cushman asked whether I would drive with her in her brougham to call on a friend of Mrs. Somerville, who had particularly desired that she and I should meet.” When they arrived, “we happily found Miss Lloyd, busy in her sculptor’s studio.”

Learning that Cobbe was an avid rider, “she kindly offered to mount me if I would join her in her rides on the Campagna. Then began an acquaintance, which was further improved two years later when Miss Lloyd came to meet … me at Aix-les-Bains; and from that time, now more than thirty years ago, she and I have lived together. Of a friendship like this … I shall not be expected to say more.”

Theirs was a happy life together. In 1864 they returned to London, “where Miss Lloyd—one morning before breakfast—found, and, in an incredibly short time, bought the dear little house in South Kensington which became our home with few interruptions for a quarter of a century.” The house, “though small, was very pretty and airy” and “we often had in it as many as 50 or 60 guests,” including naturalist Charles Darwin, political economist John Stuart Mill, poets Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning, and actor, writer, and abolitionist Fanny Kemble.

There was no doubt in their minds or in the minds of anyone who knew them that they were a devoted couple in every way. With friends, Cobbe often referred to Lloyd as “my wife,” “my husband,” “my life-friend,” “my better half,” and “ my dear friend.” A decade after they met, Cobbe wrote a long poem to Lloyd, which she included in the revised edition of her autobiography (1904). Describing their deep and enduring bonds of friendship and love, she included the following lines:

In joy and grief, in good and ill,

Friend of my heart: I need you still,

My Guide, Companion, Playmate, Love,

To dwell with here, to clasp above,

I want you—Mary.”

When Lloyd passed, Cobbe wrote, she was “a friend who knew me better than anyone beside could ever know me, and yet—strange to think!—could love me better than any other; this was happiness for which, even now that it is over, I thank God from the depths of my soul.” After Cobbe, too, was gone, novelist Blanche Atkinson (1847–1911) stated that theirs “had been such a friendship as is rarely seen—perfect in love, sympathy, and mutual understanding.” The two women rest together under a single headstone in Llanelltyd in the County of Gwynedd, Wales.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on April 24, 2025

Recent Comments