It had at least 14 writers, five directors, three production designers, numerous casting changes, and endless revisions of costumes, makeup, and hairstyles. So much for the auteur theory of film creation. But what about the “gay sensibility”? The Wizard of Oz, now 80 years old and the most beloved film of all time, was shaped by gay men—women then were rarely allowed to be decision makers behind the scenes—throughout its development. They were the first friends of Dorothy.

Friends have kind words for each other. Among the three writers to receive screen credit was Edgar Allan Woolf (1881–1943), described by MGM story editor Samuel Marx as “a wild red-headed homosexual.” While working on The Wizard of Oz, he and his frequent collaborator Florence Ryerson rewrote the script’s first draft, created the Professor Marvel character, suggested that the same actor play him and the Wizard, and also take the roles of the Emerald City’s gatekeeper, cabby, and palace guardsman.

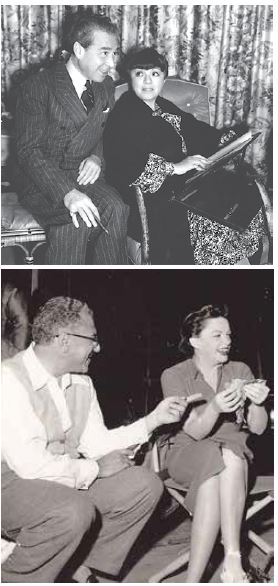

Friends often give each other advice. George Cukor (1899–1983), who directed The Wizard of Oz for only one week, transformed the entire production with his suggestions for Judy Garland’s appearance and performance. He simplified her original rouged, “baby doll” makeup, which she later said made her look “like a male Mary Pickford”; recommended Garland use her own hair, not the blond wig given her; and changed her costume to the simple, now iconic gingham dress. Dorothy became as we know her.

Celebrated as “a woman’s director,” then code words for gay, Cukor made his greatest contribution to the film when he convinced Garland to be herself in the role. Her performance, he believed, would be much more credible if she stayed away from cutsie, even in the heightened, fairytale world of Oz. He was right. Her honest and sincere portrayal centered the film, gave the story its emotional intensity, and made her a star. Garland was forever grateful.

Celebrated as “a woman’s director,” then code words for gay, Cukor made his greatest contribution to the film when he convinced Garland to be herself in the role. Her performance, he believed, would be much more credible if she stayed away from cutsie, even in the heightened, fairytale world of Oz. He was right. Her honest and sincere portrayal centered the film, gave the story its emotional intensity, and made her a star. Garland was forever grateful.

Sydney Guilaroff (1907–1997) was the hairstylist of Oz. He was 14 years old when he began his career in New York as a beautician’s assistant. Within a few years he was “Mr. Sydney” of Antoine’s, one of the city’s toniest salons. Soon he opened his own beauty parlor at Bonwit Teller. It was Joan Crawford who brought him to Hollywood and MGM, where became the studio’s chief hairstylist in 1934.

In 1938, Guilaroff became the first single man in history to adopt a son, whom he named Jon, for Joan Crawford. The state of California sued to stop the adoption, but a judge ruled not only that Guilaroff was fit to be a parent, but also that he was “more moral than most other people.” The next year, for his work on The Women, he again made history as the first hair stylist to receive a screen credit. (The salon in the film is named “Sydney.”)

The fabulous attire of Oz was the work of Adrian (née Adrian Adolph Greenburg, 1903–1959), head of MGM’s costume department and the most famous schemata maven of Hollywood’s Golden Age. It was he who was responsible for Glinda’s gossamer gown, accessorized with the latest in wands; the Munchkins’ fabulous wardrobe; the ruby slippers, which added a splash of color to a farm girl’s everyday ensemble; and all the rest of the film’s clothing.

Long rumored to be gay, he wed Janet Gaynor, also whispered about, in 1939, when he was 36. (She had worked as an usher at the newly opened Castro Theatre before moving to Hollywood, where she won the first Academy Award for Best Actress in 1927.) Their marriage did not stop gossip about their intimate lives, even after both stated publicly that they were happily married. They remained together until his death in 1959.

Of course, actors need more than direction, makeup, hairstyling, and clothes. They also need scenery and props. Enter Edwin Willis (1893–1963), head of the prop department at MGM. Willis and his staff, all of whom were gay, created, among much else, the look of the Yellow Brick Road. Working directly under him, Jack Moore (1906–1998) designed the poppy field, which he built across three sound stages.

The Yellow Brick Road, the poppy field, the ruby slippers, and much more became cultural icons, instantly recognizable to people of all generations, their symbolism and their meaning clear without comment. Dialogue became everyday sayings, slogans, catchphrases, and mantras, their intentions understood, no explanation necessary. Examples are everywhere, from the cover of Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road to Sister Boom Boom’s poster for her San Francisco Board of Supervisors campaign.

The Yellow Brick Road, the poppy field, the ruby slippers, and much more became cultural icons, instantly recognizable to people of all generations, their symbolism and their meaning clear without comment. Dialogue became everyday sayings, slogans, catchphrases, and mantras, their intentions understood, no explanation necessary. Examples are everywhere, from the cover of Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road to Sister Boom Boom’s poster for her San Francisco Board of Supervisors campaign.

For gay men, especially during an era of great persecution and deep closets, the film became beloved. The question, “Are you a friend of Dorothy?” soon meant that they were part of a great, loving, caring, and understanding community. Some may have longed for Glinda’s party dress, or the ability Dorothy had to pick up men along the highway; or a salon where a creative hair stylist could “even dye my eyes to match my gown.” Why not? We all have room for improvement.

So many more, however, found two important truths in the story. First, they need not travel to Oz to find what they were looking for. Like the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion, they had within themselves what they sought all along: brains, heart, and the courage to be themselves. Second, like Dorothy’s companions did, with their different backgrounds and experiences and the world against them, they could come together to create their own strong and supportive communities. The friends of Dorothy, birth relations or not, are our family.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on December 19, 2019

Recent Comments