By Michael Tate–

My late maternal grandmother, Mary McKay, was born on February 12, 1912. For as long as I can remember, we would gather at her home every year to celebrate her birthday with a Valentine’s Day-themed party. It was all about Black love between my extended family of cousins, aunties, and uncles.

After eating some of the best food you could imagine from the myriad covered dishes, my granny would read to us from the Call & Post, Cleveland’s local Black news weekly. Since it was Black History Month, she would focus on the special features that highlighted the achievements of nationally-acclaimed African Americans like MLK, Jr., Shirley Chisholm, Rosa Parks, and Sidney Poitier, to local unsung small business owners, teachers, and government officials like Carl and Louis Stokes.

As we grew older, this one-way storytelling evolved into lively intergenerational discussions and the occasional argument as we reflected on the joys and pains of the Black experience.

Despite the freedom and ease we had to share as a family, there was one topic that never came up: homosexuality. While we all loved the music of Johnny Mathis, Little Richard, and Luther Vandross, the dots were never openly connected that all of these men were gay. They were celebrated, but not seen. Admired, but not acknowledged. Revered, but not revealed.

As a result, I hid my true self from them and instead focused on being the quintessential “best little boy in the world.” I went to church with my mother, sang in the choir, stayed out of trouble, and earned good grades. Believing that as a gay Black man I would be a disappointment to my parents, I moved to the East Coast for college, graduate school, and my first job. Ultimately, I moved to San Francisco in 1998. While I remained close—to a point—with my family, I kept the fullness of my identity a secret.

In time, I found my voice and passion through my volunteer work with the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus and GALA Choruses (Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses); as the owner of my own business, Michael Tate Auctions; and as a team director at the Stanford Alumni Association. Despite these accomplishments, I was leading a double life. In San Francisco, I was the out (and occasionally outrageous) confident Michael who was loved and respected by friends and colleagues. But when I went to visit family, I was the strangely muted, closeted, and insecure Mike. Just being was exhausting.

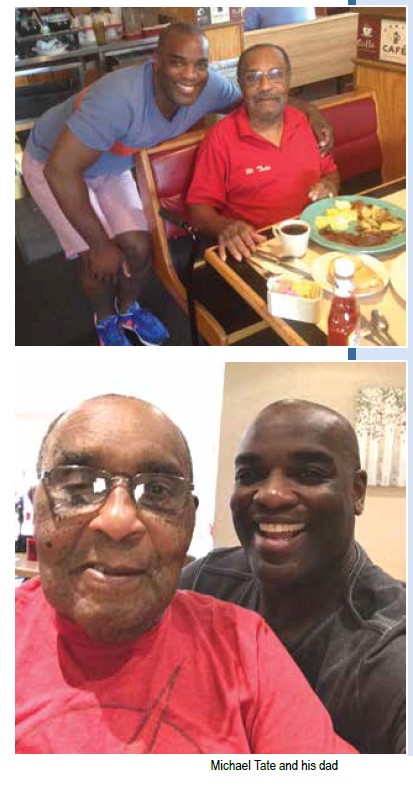

With the help of amazing friends and a compassionate, but no-nonsense therapist, I slowly started opening doors to my family that had long been bolted shut from my side for years. To my surprise, my parents were waiting with open arms on the other side. Now, don’t get me wrong; it was not a bump-free sprint for them to the next PFLAG meeting. But I can say without hesitation that my journey to authenticity was well worth the raised voices and tears shed along the way. The mutual love and respect my parents and I rediscovered for ourselves was unconditional.

So, while this month gives us all a chance to intentionally focus our attention on Black trailblazers, my personal Black heroes are my parents, Willie D. Tate and the late Doris M. Tate. With limited formal education, but hard-earned means far beyond anything their parents could have imagined, they raised two strong Black children who always spoke their minds and stood up for justice. I hold the memory of my mother close to my heart and cherish the formally frayed, but lovingly mended, relationship I have with my aging father.

With my loving partner Simon, my amazingly supportive niece, DeOnne, scores of longtime friends, a roof over my head, and food in my cupboards I am, in the words of The Clark Sisters standard, “blessed and highly favored.”

Michael Tate is the Director of the Digital & Data department at the Stanford Alumni Association. Since 2002 he has been a member of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus for which he has held several leadership positions.

Published on February 25, 2021

Recent Comments