Shortly before midnight on June 27, 1969, four police officers and two undercover agents entered the Stonewall Inn, a local bar popular in the predominantly gay neighborhood of Greenwich Village, New York City, to “observe the illegal sale of alcohol.” The bar was crowded, so they called their precinct for backup. After it arrived in the early hours of June 28, the officers began strong-arming patrons into the street and arresting them, then a typical—and frequent—police action against homosexuals.

This time, however, something amazing happened. Instead of going gently into the night and the paddy wagon, some of the bar’s patrons challenged the police, jeering at them and assailing them with anything and everything they could find. Many eyewitnesses credited Sylvia Rivera, a transgender rights activist, as the first person to fight back, but whoever it was, the action ignited three days of demonstrations, protests and rioting—and fifty years of progress toward full civil rights for LGBT Americans.

Before Stonewall

Stonewall was not the first time that members of LBGT communities fought back against police harassment and government persecution in the United States. The earliest may have been in September 1956, when inmates of the “homosexual ward” of Vacaville State Hospital protested their treatment as gay men. In May 1959, transgender women, drag queens, lesbians and gays pelted police with donuts and coffee cups at Cooper Do-nuts in Los Angeles when, not for the first time, they were hassled there by officers.

There were other incidents, too. In August 1966, a group of transgender women and gays stood up for their rights at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco. When police tried to evict them, they were routed by flying dishes, trays and flatware. The next year, after police raided the Black Cat in Los Angeles, assaulted several patrons and arrested six of them for lewd conduct because they kissed each other at midnight on New Year’s Eve, groups of protesters gathered in front of the bar over several days.

Not Just Standing Up, But Following Up

What was different about the night of June 27? Police had raided lesbian and gay bars and clubs in major cities for decades without provoking a civil rights movement. This time, however, the community not only stood up, it followed up. A young, emerging, activist generation determined that what happened at Stonewall would be remembered, making it a defining moment that changed forever the struggle of LGBTs.

With limited public awareness their task was not easy. The local newspapers reported about the raid and the riots that followed, but briefly and mostly without sympathy. The New York Times ran two brief stories about them.The New York Post headlined its five-paragraph account, “Village Raid Stirs Melee.” The Daily News titled its article, “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad.” Elsewhere, mainstream newspapers like the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times never mentioned them.

With limited public awareness their task was not easy. The local newspapers reported about the raid and the riots that followed, but briefly and mostly without sympathy. The New York Times ran two brief stories about them.The New York Post headlined its five-paragraph account, “Village Raid Stirs Melee.” The Daily News titled its article, “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad.” Elsewhere, mainstream newspapers like the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times never mentioned them.

The LGBT press was almost as limited. The New York Mattachine Society included a special supplement about Stonewall in its July newsletter titled, “The Hairpin Drop Heard Around the World,” later reprinted by the barely two year old Advocate in Los Angeles. Vector, published in San Francisco by the Society of Individual Rights, and the Ladder, the bi-monthly publication of the Daughters of Bilitis, ran short articles about the events in their October issues.

Activist Mobilizing

No matter. Members of the LGBT community spread the word using telephone trees and leaflets. By the end of July, New York lesbians and gays created the Gay Liberation Front, then the Gay Activists Alliance to press for their civil and human rights; within a few years they would have hundreds of chapters all over the country. Others organizations followed, including chapters of the Gay Student Union at numerous colleges and universities.

These new groups were different than the earlier ones. Unlike the Homophile organizations created in the years after World War, their members were not interested in being assimilated into or even being accepted by mainstream heterosexual society. Not concerned with conversation or compromise, they used publicity, awareness, activism, protest and confrontation to effect change. Stonewall came near the end of a tumultuous decade of political and social change in the U.S., so the new LGBT rights movement had plenty of examples of strategies that worked, especially militant protests to secure civil and human rights for LGBTs—the right to be themselves.

‘The Birth of Gay Liberation’

Even at the time, many hailed Stonewall as “the birth of gay liberation” and saw it as a vivid symbol around which they could organize lesbians and gay men to create aggressive, not passive, campaigns for their rights. As early as the fall of 1969, activists in New York began looking for a way to commemorate the first anniversary of the event and to encourage other groups in different cities to hold similar events.

One year later, on Saturday, June 27, 1970, some thirty self-proclaimed “hair fairies” marched from Aquatic Park down Polk Street to San Francisco’s Civic Center to commemorate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. On the same day, Chicago Gay Liberation sponsored a procession from Washington Square Park to the Water Tower, which spontaneously continued on to the Civic Center, now Daly Plaza. These were the first two pride parades held in the U.S.

Pride in the Legacy

San Franciscans commemorated the actual date of the Stonewall Riots, June 28, with a Gay-In at Golden Gate Park. The same day, some 200 members of the local Gay Activist Alliance led New York’s first “Christopher Street Day March” and Los Angeles saw its first LGBT parade down Hollywood Boulevard. At the time, only in Illinois was sexual intimacy between consenting adults legal in the U.S.

Today, 50 years after Stonewall, Pride parades and celebrations take place all over the world, thanks to the dedication and hard work of women and men everywhere who chose and choose to be their authentic selves, whatever the consequences. We owe a debt of gratitude to them all. We also owe a special bouquet of recognition to Glinda, who long before gave us both the most meaningful advice of anyone and shared the first necessary step to achieving civil and human rights: “Come out, come out, wherever you are.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

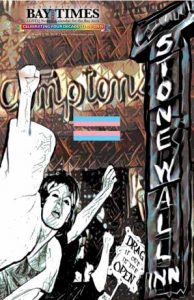

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, this issue of the San Francisco Bay Times will be featured in the national exhibit Rise Up: Stonewall and the LGBTQ Rights Movement opening March 8 at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. We thank San Francisco-based artist, activist and Commissioner Debra Walker for creating the cover.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, this issue of the San Francisco Bay Times will be featured in the national exhibit Rise Up: Stonewall and the LGBTQ Rights Movement opening March 8 at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. We thank San Francisco-based artist, activist and Commissioner Debra Walker for creating the cover.

The Newseum, which has the mission of increasing public understanding of the importance of a free press and the First Amendment, is well known for the ongoing Today’s Front Pages exhibit that brings together the front pages of newspapers from around the country ( http://www.newseum.org/todaysfrontpages/ ). For this important Stonewall anniversary year, Today’s Front Pages, in conjunction with Rise Up, is bringing together the front pages of LGBTQ papers from across the country. We are proud to be included.

The protests following the June 1969 raid of the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village are considered to be the catalyst that inspired the modern gay liberation movement and the ongoing fight for LGBTQ civil rights. The Compton’s Cafeteria Riot that occurred in San Francisco three years before Stonewall, along with certain other events related to the gay and especially to the transgender community’s struggle for basic rights, are also being recognized more now for their historic importance.

Rise Up launches a yearlong program series at the Newseum featuring journalists, authors, politicians and other newsmakers who have led the fight for equality. Through powerful artifacts, images and historic print publications, the exhibit explores key moments of gay rights history, including the 1978 assassination at San Francisco City Hall of Supervisor Harvey Milk, the AIDS crisis, U.S. Rep. Barney Frank’s public coming out in 1987, the efforts for hate crime legislation, the implementation and later repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the fight for marriage equality.

Rise Up also looks at popular culture’s role in influencing attitudes about the LGBTQ community through film, television and music, and explores how the gay rights movement harnessed the power of public protest and demonstration to change laws and shatter stereotypes. The exhibit, which includes educational resources for students and teachers, will travel nationally after its run at the Newseum ends on December 31.

For more information: http://www.newseum.org/

Recent Comments