By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

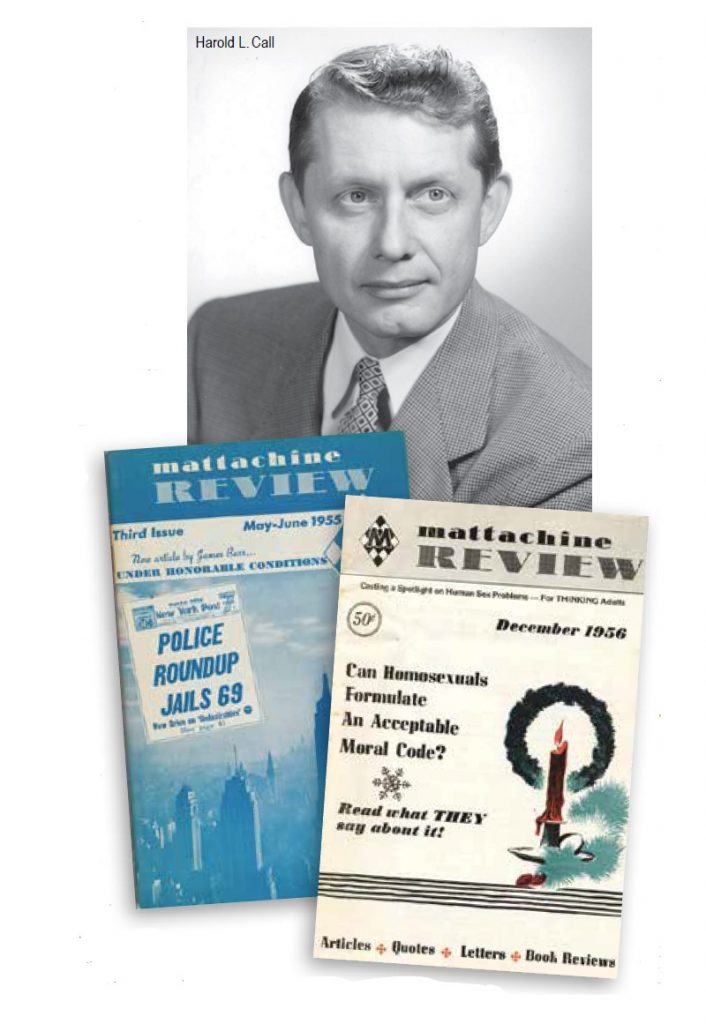

Writing in The Mayor of Castro Street, journalist and author Randy Shilts christened Hal Call (Harold Leland Call) San Francisco’s “first permanent gay activist.” One of the most important and controversial figures of the homophile movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Call helped to shape its ideology and direction until the campaign for mainstream understanding and acceptance of lesbians and gays was superseded by the demand for direct action after Stonewall.

In an era of conformity and control, when too many people feared the very real consequences they faced for being openly lesbian or gay, Call was among the first to speak about homosexuality on radio and television, appearing as himself, using his real name. Born in Missouri in 1917 and educated as a journalist, he moved to San Francisco in 1952 after being acquitted of “lewd conduct” in Chicago.

He arrived at a difficult time for lesbians and gays in the United States. Two years earlier, in June 1950, the Senate began to investigate the government’s employment of homosexuals. The results were not encouraging. Homosexuality had long been illegal in the U.S., but now gay men and women were being labeled both as undesirable employees and as threats to society, not for anything they did, but for who they were.

The Senate’s findings were bolstered in 1952, the year Call moved to San Francisco, when the American Psychiatric Association classified homosexuality as a “sexual deviation” and a mental illness. The next year, President Dwight Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which declared homosexuals to be security risks and prohibited them from working for the federal government. The changes drove people deep into their closets, not out into the streets.

The Mattachine Society, which held its first meeting in Los Angeles in November 1950, was the only gay rights organization to exist then. It was deeply divided. Not only had the original leadership become hugely controversial because of their affiliations with the Communist Party, but also two views of how to move forward had emerged among its members.

Some saw homosexuals as a minority group with their own culture that needed to organize and work for its rights. Others believed that equality would come only by assimilating “as men and women whose homosexuality is irrelevant to our ideals, our principles, our hopes, and aspirations.” They wanted to educate the public that “our only difference is an unimportant one to the heterosexual society, unless we make it one.”

After a bitter internal struggle led to the resignations of the original leadership, Call became president of the Society. Arguing that “the sex variant is no different from anyone else except in the object of his sexual expression,” the group turned from considering any political activism to research, education, and social service. Their goal was sexual freedom through social understanding and acceptance, not political activism.

Call agreed: knowledge and influence, not challenge and protest that would “foment an ignorant, fear-inspired anti-homosexual campaign,” were key. In 1954 he and associate Donald Lucas founded Pan-Graphic Press to publish books, both fiction and nonfiction, that presented homosexuality objectively and explained it accurately. It remained a successful business for years. It also printed The Mattachine Review, which Call edited,and early issues of The Ladder for The Daughters of Bilitis and other homophile literature.

As one of the first Americans to proclaim his “sexual deviation” publicly, Call began working with social scientists, local attorneys, journalists, community leaders, and other professionals to help them better understand—and hopefully enable the public to better understand—what homosexuality “was all about.” Many homophiles wanted to downplay their “sexual expression,” but he was determined to educate the sexually uninformed by being open about it.

“Homosexualism,” he told listeners to a 1958 radio program on KPFA, “is just one of the things that exists in nature. It always has been with us, as far as we know, and always will be as far as we expect. It seems that no laws, no attitudes of any culture … have ever been able to stamp it out or even essentially curb it.” He worked to “educate the public” about difference, so difference “will no longer be of any significance.”

On September 11, 1961, Call appeared on The Rejected, the first documentary about gay men (nothing about lesbians was included) shown on American Television. Produced by KQED in San Francisco, it examined “who are the gay ones, how did they become gay, how do they live in a heterosexual society, what treatment is there by medicine or psychotherapy, how are they treated by society, and how would they like to be treated?” Call presented the homophile viewpoint.

Many in the community were satisfied with how Call described them as ordinary citizens, but not everyone was pleased. A newer generation of activists thought the program was pandering. They believed that gays should be themselves without apology or accommodation to the conceptions of mainstream society. They held that direct political action, not supplication, was the way to equality.

The Mattachine Society had entered a period of decline by the mid 1960s, but for many, Call remained the face of the “sexual variant.” In 1964, he contributed to a Life magazine article that sought to explain “homosexuality—and the problem it poses.” The same year he was interviewed for The Homosexual, the first network documentary to discuss homosexuality. No sponsor was willing to buy advertising time on it. Both showed that, after a decade of work, public perception had hardly changed.

By then The Mattachine Review was being published only sporadically; the last issue appeared in 1967, which was the same year Call opened the Adonis Bookstore. The first gay bookstore in the United States, it carried periodicals and books as well as explicitly adult material, much of it created by Grand Prix Photo Arts that he founded in 1968. What became the Circle J, the first gay adult theater in San Francisco with a live erotic stage show, followed soon after; it finally closed in 2005.

Some were disappointed that a former leader of the homophile movement had become a “mere pornographer,” but Call was unapologetic about all of it. “What’s the use in battling for sexual freedom without having any?” he asked. He died in San Francisco on December 18, 2000. He was 83.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on August 11, 2022

Recent Comments