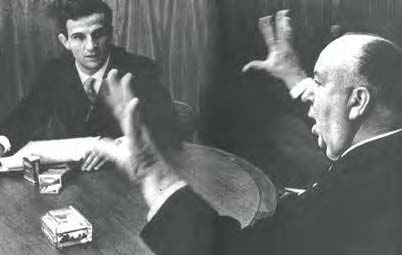

In 1966, film critic-turned-director François Truffaut interviewed Alfred Hitchcock for the seminal book, Hitchcock/Truffaut. Their weeklong Q&A (with the help of an interpreter) was Truffaut’s effort to show that, as a filmmaker, Hitchcock was an artist—in his mind, the World’s Greatest Director—and not “just” an entertainer as was popular opinion of the day.

In 1966, film critic-turned-director François Truffaut interviewed Alfred Hitchcock for the seminal book, Hitchcock/Truffaut. Their weeklong Q&A (with the help of an interpreter) was Truffaut’s effort to show that, as a filmmaker, Hitchcock was an artist—in his mind, the World’s Greatest Director—and not “just” an entertainer as was popular opinion of the day.

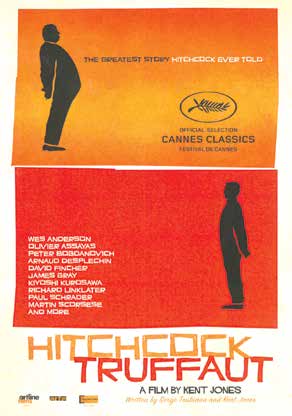

Now, with the documentary feature, Hitchcock/Truffaut, opening December 11, film festival director/writer Kent Jones has a made a loving, film geek tribute to the book, the filmmakers themselves, and the contemporary directors who have been influenced by Hitchcock/Truffaut. Jones’ film is both artful and entertaining, deftly using film clips, photographs, quotes, passages from the edition, and interviews with Martin Scorsese, Richard Linklater, and Olivier Assayas among others, to discuss the magic and power of Hitchcock’s work.

The documentary addresses how the author and subject came from different generations, backgrounds, and approaches to cinema and the importance of their collaboration. Hitchcock was a rigorous visual artist and controlled craftsman, a point echoed by interviewees David Fincher and Paul Schrader. Truffaut, a Cahiers du Cinema critic, who subscribed to the auteur theory of filmmaking, took on the book project “as if it were a film.” Their collaboration paid off. As the film Hitchcock/Truffaut shows, both directors gained more respect, and their friendship lasted for the remainder of their lives and careers.

Jones provides a few scenes that tie the filmmakers together, as when he shows how both directors recall a moment from their childhood where they spent time in jail, or when Hitchcock and Truffaut discuss the latter’s approach to a pivotal sequence in The 400 Blows. These are affectionate moments that magnify the camaraderie between the two filmmakers. Jones also presents the world of these directors off-screen.Hitchcock/Truffaut includes a few terrific shots of a photo session with the filmmakers, and a nice nod to Hitchcock’s wife, Alma Reville, who is seen briefly in some home-movie footage.

At its best, the documentary serves as a companion piece—and, at times, as a mirror—to the book as a cinema primer. The film showcases Hitchcock’s inimitable visual style and themes. In his mini-lessons, Jones unpacks how editing is used to expand or contract time in a film. He illustrates how Hitchcock uses space both in a room and in an exterior shot from the film The Birds to generate emotion or create unease.

The use of film clips in these mini-master classes emphasizes the points being made better than any film still or interview text in the book does. Seeing the scene of a man pacing on a glass floor in Hitchcock’s early film, The Lodger, emphasizes the “wow” factor better than reading about it. Likewise, when Hitchcock explains why he wants actor Montgomery Clift to look up at a building across the street in I Confess, the clip of the scene shows how the director’s decision, which Clift objected to, was correct and why.

A few lengthy sections of the documentary analyze specific scenes and themes in Hitchcock’s classics. An interesting discussion of the director’s use of high angle shots evolves into how the themes of sin, guilt, and God are all interrelated in the director’s work. A key scene from Psycho is used to explore this point visually, and it provides an “a-ha!” moment. A discussion of a favorite theme of the innocent-man-unjustly-accused narrative (e.g., The Wrong Man) makes connections to the psychological underpinnings of characters. Even the most casual of moviegoers will respond to these points because they are so well articulated.

There is also a fun montage of “fetishized” objects in Hitchcock’s films, from a key in Notorious, and the glass of milk in Suspicion, to the title object of Rope. Sadly, a discussion of dreams does not include the famous Salvador Dali dream sequence in Spellbound. Other minor case studies devoted to repeated visuals that Hitchcock employed—such as scenes of characters falling from buildings, or the use of rear projection—also seem underdeveloped.

However, there is no finer moment in the film than a lengthy discussion about Vertigo. As Scorsese and others wax poetically about this classic, which was long kept out of circulation, the analysis of point of view, and the ideas of fantasy and realism, visual motifs, and even plot holes in the film could be expanded to comprise a separate documentary.

Hitchcock/Truffaut genuflects appropriately in the discussions of Hitchcock’s oeuvre. If the film is a bit slight at 80 minutes, this is a minor complaint. The book Hitchcock/Truffaut was more comprehensive. The documentary is deliberately not. However, this is hardly a drawback. If Jones’ film prompts viewers to read (or re-read) the volume to gain more insights about Hitchcock’s work touched on in the film, it has done its job.

© 2015 Gary M. Kramer

Gary M. Kramer is the author of “Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews,” and the co-editor of “Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.” Follow him on Twitter @garymkramer

Recent Comments