By Andrea Shorter–

“I found that my wounds begin to heal when the voices of those endangered by silence are given power. The silence of hopelessness, of despair buried in the depths of poverty, violence, racism is more deadly than bullets. The gift of light, in our compassion, our listening, our works of love, is the gift of life to ourselves.”

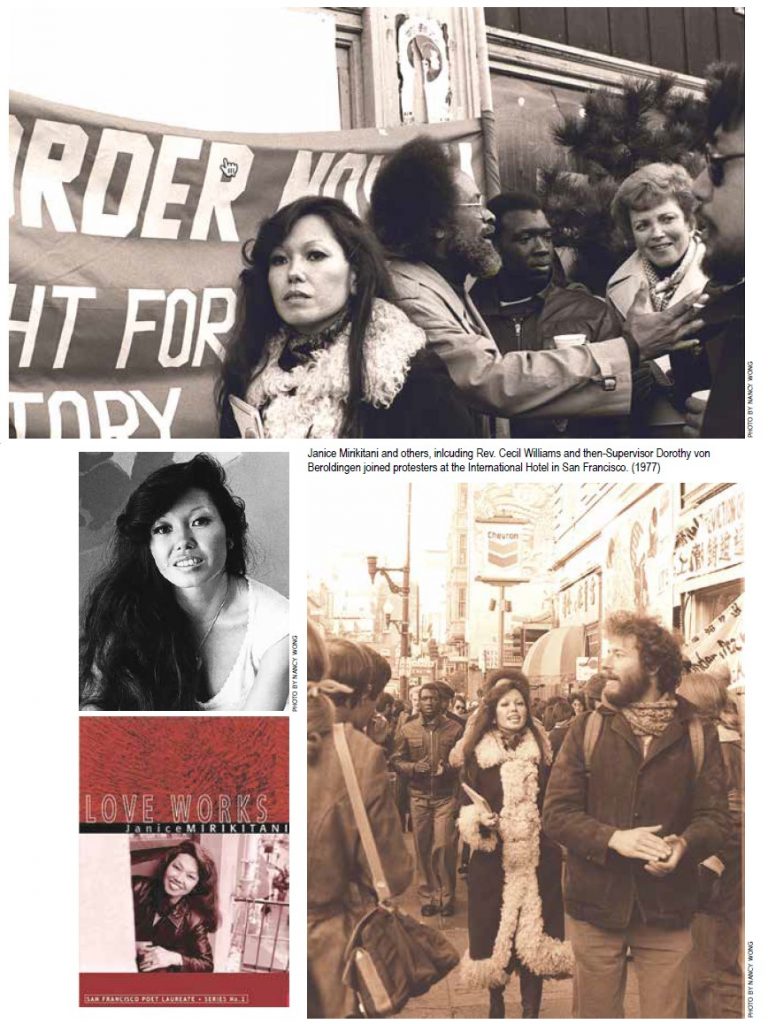

—Janice Mirikitani

Janice Mirikitani stood tall within the deep recesses of the heart of San Francisco. In countless respects, she fiercely and gracefully personified the heart of her beloved city. On July 29, the collective heart of San Francisco broke at the news of the sunset of its radiant dear heart at the day’s dawn. For many, there was a realization that San Francisco would never be the same without her.

Perhaps most famously known as the co-founder and president of GLIDE Memorial Church, and as the wife and partner to GLIDE pastor Reverend Cecil Williams, she was a vital force and spirit in the creation of one of the most celebrated centers of worship and communion that was radically and unapologetically inclusive, progressive, and a fierce advocate for the city’s most vulnerable citizens. Whatever your religious denomination, or no denomination, whether you were of high or struggling station in life, homeless or sheltered, of means or in poverty, whatever your racial or ethnic makeup, color or hue, there was a place for you at GLIDE the moment you walked in the door.

Mirikitani’s belief in “caring dangerously—daring to take the risk to open yourself up to somebody else” was a cornerstone, the rock upon which the church would be built and progress. The embrace, inclusion, and empowerment of LGBTQ people to live as perfectly authentic, equal, loved, and vital human beings would prove central to GLIDE’s mission and thrive of caring dangerously.

When I first landed into the activist hotbed of San Francisco some 30 years ago, one of the most common questions asked of me was, “Have you been to GLIDE Memorial yet? You must experience GLIDE. It feeds the hungry, has an incredible choir, and is just good for the soul. And, when you do go, you really must meet Jan and Cecil.”

When I finally got myself to GLIDE one Sunday morning, I was admittedly overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of its packed to the rafters congregants, its joyful and affirming celebration, its wildly diverse, mind-blowing, shake the walls choir, so radical it replaced the phrase “saved a wretch like me” in the sacred hymn “Amazing Grace” with an affirming declaration that not one of us was a wretch within or outside of these church walls.

We were seated shoulder to shoulder for what seemed only minutes before we were all moved to rise, clap, and sing with the choir. I sat in between my brother and a woman who was recently homeless, next to her an older couple from Pacific Heights. Educated as a sociologist and raised a natural born Midwestern skeptic, I remember trying so hard to be an objective, detached participant observer of the grand theatrics of it all.

After the third or fourth revised song, my heart gave way. This was more than spectacle. It was real; it was meaningful; it was a force of and for community. These people really seemed to mean what they were preaching, singing, walking, and talking about: love, care, inclusion, and empowerment. While I didn’t come through those doors in need or want of spiritual repair from the brokenness of addiction, homelessness, abuse, or just plain being down and out as that day’s fellow congregants might have, I certainly felt more lifted, grounded, and whole when I walked out those doors. I knew then that I just had to meet Jan and Cecil.

Not long after my first Sunday at GLIDE, I met them and began a truly beloved kinship that would become a defining hallmark and touchstone along my own colorful, storied up and down journey in the hilly City of St. Francis. Along the way, I learned from them the history of GLIDE, their individual and collaborative paths as civil and human rights activists, and what they built together meant to thousands of residents fed, clothed, cared for, and housed by the resources of the church.

Yes, they were revered celebrities for their radical irreverence for traditional Protestant ways of putting faith to work and action towards healing wounded souls, speaking truth to power. It wasn’t so much their celebrity that impressed me, though. It was that they were also keenly self-aware of their own human-ness—wounds, traumas, capacities to renew, from which they apparently found strength to help others renew.

Jan was our poet laureate. An accomplished literary figure of premiere importance in the lifting up of Asian American literature, arts, and culture, she wrote volumes of poetry that often channeled her own personal struggles and troubles as a survivor of incestuous sexual abuse as a child, internment as a Japanese American, and growing into her own liberation as an empowered woman. Uniquely lyrical, visual, and often sensual, she was dynamic and her poetry captured the ever-changing landscape of San Francisco, celebrating its mosaic of ethnic diversity, forgotten histories, aspirations, and capacities to be and do better than its present self. She taught creative writing to women at GLIDE to help them claim and use their own unique voice to heal, repair, and liberate from the traumas of domestic and family violence, street violence against women, sexual assault, addictions, mental trauma, and homelessness.

A longtime fighter for LGBTQ equality, she could tell you a few colorful stories about the days of Harvey Milk, life in the aftermath of his assassination, advocating for treatment and supports in the burgeoning, harrowing HIV/AIDS crises of the 1980s, standing up as an ally for marriage equality, and GLIDE’s inclusion of LGBTQ identified clergy, staff, directors, cooks, teachers, in pretty much every aspect of the GLIDE community.

We connected largely in common cause for the safety and uplift of women and children survivors of violence, social justice for women of color, and women’s political representation and power. The uplift of women’s voices seemed to be her mission eternal. She served as a touchstone and phone call away or drop in reality check for myself and others as we worked to elevate the status of especially our most vulnerable sisters, including those impacted by the justice system.

On occasion I was invited to speak at GLIDE, mostly about the status of women. For one International Women’s Day, I must have prepared at least seven pages of single-spaced notes about the status of women in San Francisco, in the U.S., and, of course, globally. Educated as a sociologist, I over-prepared for my allotted 15 minutes at the pulpit.

I started off okay, until I broke away from speaking from my volume of notes, and just spoke plainly. As I did so, the energy from the pews clearly shifted. Afterwards, Jan took me by the hand and whispered in my ear: “You did good. You were most wonderful without the notes. You are enough without the notes. That’s why we wanted you to speak. You are enough.” Never again did I publicly speak from notes at GLIDE or pretty much anywhere else. Well, at least no longer from seven pages of notes.

Of the many words from a wise woman of her own making, if there is any one thing I learned repeatedly from Jan Mirikitani—in our own cherished kinship, or from observing her with others in need of little encouragement, affirmation, or just a little love—is that we are all indeed enough. Seeing and embracing ourselves—as women, as young people, as LGBTQ, as survivors, as being enough—is where our liberation begins, progresses, and flourishes. It’s not always easy this work of being enough, but that’s the journey; that’s the work, and that’s the gift. But it doesn’t mean you have to go it alone. No one is alone, truly. Creation of community, movement, and spirit in which we “care dangerously” is her eternal gift to us all.

We can now imagine this earthly force of nature now reunited with her beloved friends Maya, Gwendolyn, Audre, Toni, Ntozake, and other sister poet-activists all together as a chorus of “bad women who celebrated themselves.” I will miss our time together, our calls every now and then just to check in, touch base, collaborate, conspire, commiserate, and celebrate. We are each enough to carry on in spirit, action, and with heart the work of loving and caring dangerously in this lifetime.

To love and be loved by such a relentless force for justice, equality, peace, compassion, service to others, and celebration of self-love will remain the enduring gift and blessing of Janice. Like so many, my heart is broken at her sudden loss, but it is an undeniably fuller and grateful heart for having lived in the time and gift light of Janice Mirikitani.

Andrea Shorter is a longtime Commissioner for the City and County of San Francisco, now serving on the Juvenile Probation Commission after 21 years as a Commissioner on the Status of Women. She is a longtime advocate for gender and LGBTQ equity, voter rights, and criminal and juvenile justice reform. She is a co-founder of the Bayard Rustin LGBTQ Coalition, and was a David Bohnett LGBT Leaders Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Published on August 12, 2021

Recent Comments