Julian Cox, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s founding curator of photography and chief administrative curator, recently took time to talk with us about Keith Haring’s pop art and politics ahead of the opening of the exhibit Keith Haring: The Political Line at the de Young.

Julian Cox, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s founding curator of photography and chief administrative curator, recently took time to talk with us about Keith Haring’s pop art and politics ahead of the opening of the exhibit Keith Haring: The Political Line at the de Young.

San Francisco Bay Times: Please talk about Haring’s self-portraits, of which he made many. What do you think they reveal about the artist?

Julian Cox: Haring made self-portraits in a variety of media and particularly relished turning the camera on himself. The many Polaroid SX-70 self-portraits that he made between 1980 and 1988 reveal his impish, shape-shifting identity. While Haring enjoyed performing and play-acting, the best of his self-portraits (such as the 1985 painting on page 3 of the San Francisco Bay Times) show a more serious side.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you speak to the recurring symbols and motifs in Haring’s work, their possible meaning, and his study of semiotics at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City?

Julian Cox: Haring studied semiotics at SVA and reveled in exploring the power of words and linguistic systems. He was a close friend of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, who inspired his interest in language and its symbolism. As for the symbols and visual vocabulary that proliferate in his work, Haring remarked in his journals: “I paint images that are derivative of my personal exploration. I leave it up to others to decipher them.”

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you expound on Haring’s views of capitalism and his own struggle with commercialism and consumerism?

Julian Cox: Haring was an outspoken opponent of the negative effects of capitalism, and he railed against consumerist excess in his art. As his career blossomed, however, he became more conscious of the complications of money and was never entirely comfortable with his commercial and art world success.

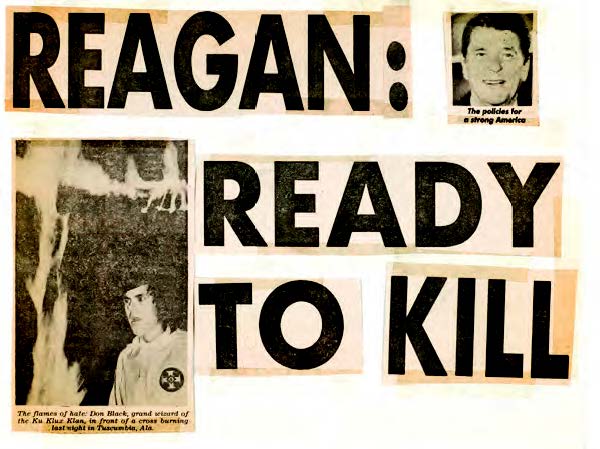

San Francisco Bay Times: Please offer a little background about the powerful “Reagan: Ready To Kill” image. Can you talk about Haring’s use of this medium?

San Francisco Bay Times: Please offer a little background about the powerful “Reagan: Ready To Kill” image. Can you talk about Haring’s use of this medium?

Julian Cox: Haring was absolute in his desire for his work and its message to reach as wide an audience as possible. Some of his earliest street works after art school were collages composed of cut-up headlines from the New York Post that were cheaply photocopied and pasted up on walls and lampposts, guerilla-style.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you describe Haring’s views on apartheid, racial inequality, and the motifs he uses in the next two images shown here?

Julian Cox: Haring resisted and campaigned against racism in all its forms. He was deeply affected by the racial intolerance that his friends, including the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, experienced in their everyday lives. He understood how his art could serve the causes that he cared about. His monumental acrylic-on-canvas painting Untitled (Apartheid), 1984, was made into posters, badges, and t-shirts and sold widely to help support the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa and the release of its most vociferous opponent, Nelson Mandela.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you speak to Haring’s relationship with fellow artists, and how they influenced and inspired each other?

Julian Cox: Haring was very indebted to Andy Warhol as a friend and guide in matters of art and life. They had a tremendous respect for each other and Warhol went out of his way to support the younger artist’s career. Upon Warhol’s death in 1987, Haring reflected in his journal: “He became a teacher for a generation of artists now, and in the future, who grew up on Pop, who watched television since they were born, who ‘understand’ digital knowledge.” Haring also had a warm (but competitive) relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose work he admired greatly.

Julian Cox: Haring was very indebted to Andy Warhol as a friend and guide in matters of art and life. They had a tremendous respect for each other and Warhol went out of his way to support the younger artist’s career. Upon Warhol’s death in 1987, Haring reflected in his journal: “He became a teacher for a generation of artists now, and in the future, who grew up on Pop, who watched television since they were born, who ‘understand’ digital knowledge.” Haring also had a warm (but competitive) relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose work he admired greatly.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you explain the significance of the pink triangle (see page 29), and the impact it has made on viewers?What are some of the ways in which Haring has contributed to the fight against the AIDS epidemic?

Julian Cox: Haring campaigned vigorously and raised funds for AIDS research (alongside artist friends such as Andy Warhol) and he addressed the condition head-on in his art. The triangular pink canvas that he created for Silence=Death is unmatched in poignancy and execution. It is a profoundly moving work that combines joy and despair in equal measure.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you describe the format Haring uses in the layout of the four panel image (see page 29)? Why do you suspect he employs this sort of composition? What are its strengths?

Julian Cox: As a child, Haring loved the cartoons of Charles Schulz and Walt Disney, and he mined a variety of images from popular culture as subjects for his art. He also borrowed the comic-strip format, which suited his inclination towards a more dynamic, kinetic form of drawing and his desire to break the narrative down into distinct parts.

San Francisco Bay Times: Please describe what is going on in this picture (black vertical image, below right). Can you also explain how Haring’s artistic style and his use of various media were particularly effective in communicating messages of social and political change?

Julian Cox: Haring’s subway drawings are among the most magical and mercurial of all his works. Between 1980 and 1985, he made thousands of chalk drawings throughout the New York City subway system, creating mischievous and inventive compositions. Executed on expired advertising panels, the drawings that Haring made on these “blackboards” were each a kind of performance, carried out with speed and assurance on the subway platform in the moments after a train departed and before another arrived. The rapidity of these creations made for distinct, readily recognizable imagery and a vocabulary of forms that gave the work the power of a mass media campaign.

San Francisco Bay Times: Can you speak to how some of the political and social issues that Haring addressed remain relevant today?

Julian Cox: Haring notably remarked: “An artist is a spokesman for a society at any given point in history. His language is determined by his perception of the world we all live in. He is a medium between ‘what is’ and ‘what could be.’” While the issues that Haring cared so much about are necessarily locked into a very specific moment in recent history—the 1980s—they translate powerfully across time. Racism still plagues our culture, as does environmental neglect. The excesses of consumer culture and technology are pervasive nowadays, and Haring was prescient in his concerns about these issues. His art inspires reflection on these matters, as well as sense of awe at the power and conviction of his ideas.

Recent Comments