By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

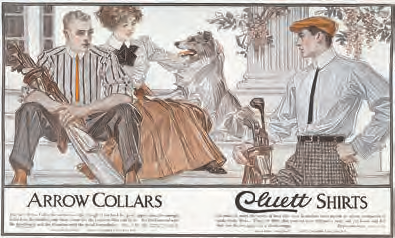

During his heyday from 1905 to 1930, the Arrow Collar Man was often described as one of the most handsome and certainly one of the most desirable men in the United States. He appeared in more magazines than the most acclaimed stars of stage and film, and at the height of his popularity, he received more fan mail than any of them, as many as 17,000 letters addressed to him in a single month. Men wanted to be like him. Women wanted to be with him.

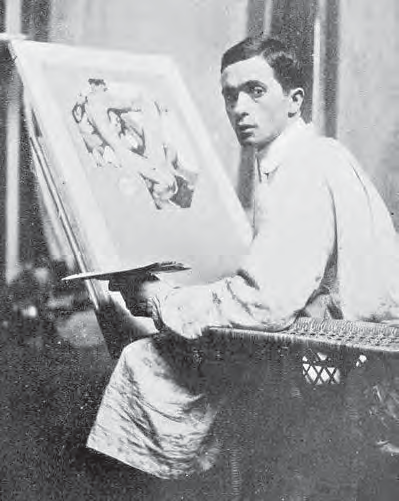

Created by a clothing manufacturer and a New York advertising agency, he was brought to life by a successful artist and illustrator, Joseph Christian Leyendecker (1874–1951), who modeled him after a specific individual, his life partner of 50 years, Charles Beach (1881–1954). At a time when companies were just beginning to sell their products with image advertising, the two men imbued the Arrow Collar Man with a virtually complete gay iconography, then unnoticed by most consumers, which has now endured for more than a hundred years.

This fictional individual was much more than a figure to sell celluloid shirt collars, otherwise rather bland and boring products. He was the nation’s first male sex symbol, and for decades he personified modern American manhood. Even after detachable collars became a relic of an earlier time, he remained a national role model: tall, handsome, and physically fit, as well as stylishly dressed, at ease with himself, and popular with both women and men—a gay man as the quintessential masculine ideal.

His was the image of elegant, sophisticated masculinity that Irving Berlin, deemed “the nation’s songwriter” by The New York Times, wanted listeners to bring to mind in his perennially popular song “Puttin’ on the Ritz,” which has been sung by everyone from Fred Astaire and Clark Gable to Gene Wilder and Taco, who all performed it wearing tuxedos or white tie elegance. Consider these lyrics:

“Have you seen the well-to-do

Up and down Park Avenue?

High hats and Arrow collars

White spats and lots of dollars

Spending every dime for a wonderful time.”

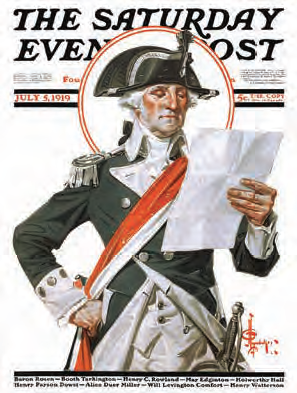

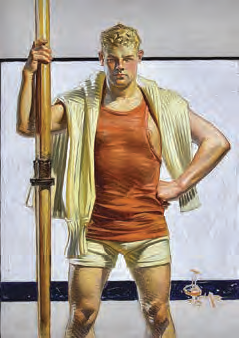

Leyendecker portrayed a range of men in his commercial work, from founding fathers to friendly policemen, but his most celebrated images, like the Arrow Collar Man, presented many of the enduring masculine icons—including sailors, lifeguards, and athletes (no leather men yet)—who are still with us. President Theodore Roosevelt, a staunch advocate of “manly athleticism as a means toward a patriotic and moral good,” praised Leyendecker’s illustrations for depicting “a superb example of the common man.”

With his broad shoulders and slender waist, “chiseled features,” and masculine desirability, Beach was Leyendecker’s favorite model, not only for the Arrow collar advertisements, but for many of his images of the modern American man. The two men could not have been more different. Leyendecker was short, thin, and “very average looking,” with “an unnaturally sallow complexion and a weak jaw.” One biographer described him as “being socially awkward and so painfully shy that he stuttered when any person of authority asked him to speak.”

According to the illustrator Norman Rockwell, whose own work was greatly influenced by Leyendecker and who knew both men well, Beach was “tall, powerfully built, and extraordinarily handsome,” someone who “looked like an athlete from one of the Ivy League colleges.” Rockwell also remembered him as being “always beautifully dressed. His manners were polished and impeccable.” Another admirer described him as “confident and charming,” having “an Adonis-like figure with a narrow waist and a flat stomach.”

Twelve years younger and six inches taller than Leyendecker, Beach might have seemed an unlikely mate, but the couple apparently liked each other immediately. Only a few months after they met, Beach began modeling exclusively for him and spending the rest of his time working at odd jobs at the studio. Soon he was doing a dozen tasks for the artist and eventually became his agent and general manager. According to Rockwell, “Beach transacted all Joe’s business for him, did everything but paint his pictures.”

Leyendecker needed all the time he could find for his work. Between 1899 and 1943, he created more than 300 covers for The Saturday Evening Post alone. Many were scenes of wholesome Americana, charming and sweetly sentimental, such as a youngster’s first date, the Easter parade, and a mother and child’s Christmas prayer together. Others were infused with a homoeroticism that was not recognized by his mainstream audience—what gay men at the time thought of it is not known—but is unmistakable when noticed.

Some covers, however, were frankly homosensual, including the one he did for the August 6, 1932, issue of the Post, to celebrate the opening of the Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Its highly oiled, amazingly handsome, and brilliantly muscled athletes, by themselves enough for any erotic gay daydream, wear tightly clinging, physically defining clothes—what there are of them—that actually do not leave much to imagine. The testosterone seems to leap from the page like the scent in a modern perfume insert.

Leyendecker’s homosocial imagery for Arrow may be more famous, but his illustrations for a series of Ivory Soap advertisements probably are the most blatantly erotic and revealing. They had to have been reviewed by the company, its advertising agency, and the editorial board of every magazine they appeared in, but apparently none of them noticed anything inappropriate about men watching each other taking showers in a locker room, admiring each other while swimming nude, and bathing together on board a ship during the Great War.

Perhaps Leyendecker’s most daring commercial illustration was for an Ivory Soap advertisement that appeared in the early 1900s. It shows a fully covered man, wearing a somewhat flamboyant head to foot changing robe. Only his face and hands are uncovered, but just below his corded midriff, while he admires his bar of soap, the extent of his masculinity is apparent. Gay men everywhere must have been as excited as the model was to see his portrait in their favorite magazine.

Leyendecker’s classic masculine icons are still with us. Never mind that they exemplify an elite white masculinity that was hardly representative of the diversity of American men, then or now. The language of male imagery that Leyendecker helped create is still at least producing positive emotions to sell products.

The artist’s choices made all the difference. Unlike other illustrators of his time who portrayed handsome men in their work, commercial or otherwise, Leyendecker chose to emphasize not only the physical beauty of his models, but also their sexual allure and especially their flirtatious desire for each other. Depicting subtle and not so subtle poses, he included a homoeroticism that mainstream readers may have missed completely, but that would have been unmistakable to his gay admirers. Wherever they lived, they could see that they were not alone in the world.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on January 25, 2024

Recent Comments