By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

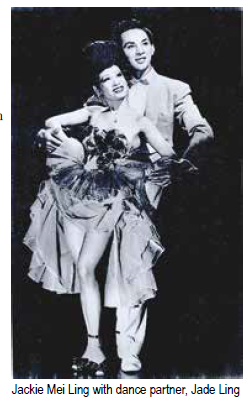

As a dancer, Jackie Mei Ling (1914–2000) could do it all. During San Francisco’s Golden Age of Nightclubs from the 1940s to the 1960s, he successfully appeared before the public in everything from formal attire to drag. Creative, eclectic, and resourceful, “his dance routines,” wrote the historian Anthony W. Lee, “neither followed a preferred model nor seemed to present any one particular style.” He not only “choreographed complex dance sequences for himself and his partners, but also designed the various costumes for each of their performances.”

Although he was born in Utah, Mei Ling grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He became interested in dance at an early age, studied with Walton “Biggy” Biggerstaff (1903–1995) at his Jackson Street studio; the Ballet Company of San Francisco; and very briefly with Theodore Kosloff in Los Angeles. He was appearing in nearby San Fernando Valley with then-partner Jadin Wong when Charlie Low, owner of Forbidden City, invited them to appear in his club. They quickly became the night spot’s featured performers.

Mei Ling introduced Biggerstaff to Low around 1940 and he became Forbidden City’s principal choreographer and producer for the next 14 years. Many of his creations showcased what members of the audience, mostly white tourists, imagined the “exotic orient” to be; some, like 1942’s “The Girl in the Gilded Cage,” received extensive publicity in periodicals as diverse as the Carnival/Show and Collier’s Weekly, then a widely-read family magazine. Openly gay, Biggerstaff was survived by his “life companion” Charles E. Lindsley.

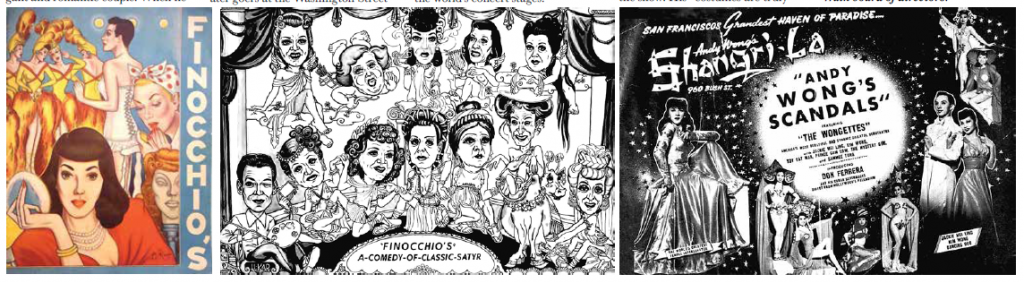

According to Lee, all of Mei Ling’s dance partners knew he was gay, too, which evidently bothered neither them nor the club owners. Public disclosure, however, would have damaged his image as one of an elegant and romantic couple. When he appeared at Andy Wong’s Shangri-La in 1942, his photograph graced the cover of the souvenir program twice, identified as himself with partner Kim Wong, but unnamed, as “the world’s greatest female impersonator.” Reviewing the show, however, the Examiner revealed it was “Jack Mei Ling, impersonator and dancer.”

He also was discrete when he appeared in drag at Finocchio’s. “I had an agreement with them that if there were any Chinese in the audience, I wouldn’t dance,” he told the historian and filmmaker Arthur Dong in an interview. “I didn’t want [my family] to see me at Finocchio’s.” In 1946 the Chronicle reported one surprise appearance there as a lark, the dancer “amusing himself and amazing the customers by putting on a wig and female dress and popping up in the last show.”

Mei Ling was not the first performer of Chinese heritage to appear as a female impersonator in San Francisco. Some 50 years earlier, Ah Ming (1828?–1892) dazzled theater goers at the Washington Street Theater, where he earned $6,000.00 a year, a fabulous amount in those days. He was, wrote the San Francisco Call, “perfection in his special line, which was peculiar and a difficult character to assume … the coy manners and deportment of the Chinese girl of the period.”

Not all of his contemporaries were as beloved. According to the Call, “There is a Chinese female Impersonator named Me Chung Chen, whom the theater-goers of little China have no use for. They claim he is a bad actor and ought not to be on the stage.” When he appeared at the Chinese Theater on Jackson Street in 1903, “a serious riot occurred,” with “eggs and rotten vegetables of all descriptions” being “hurled at the actors by an infuriated mob of motley Celestials.”

Others fared much better. When Lou Yoke appeared at the San Francisco Hippodrome in 1916, the “Chinese female impersonator caused much admiration and merriment with his act.” So did Roy Chan, a “native-born Chinese female impersonator with [a] cultivated soprano voice.” Known as “the Chinese Nightingale, he performed at the Knights of Columbus Hall in 1922 with other performers for a charity fundraising event. Almost nothing else is known about either man.

Li-Kar (?–?) may or may not have been Chinese, although many believed he was; others thought his heritage was Indonesian. In a brief biography that appeared in Finocchio’s souvenir program of the late 1940s or early 1950s, which he probably wrote himself, he is said to have trained as a commercial artist at Otis Art Institute and at Chouinard Art Institute, both in Los Angeles. He then enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago and, still a student, became a freelance artist for two of Chicago’s largest newspaper advertising concerns.

Li-Kar first appeared at Finocchio’s in 1938. He was billed last of nine performers as Lee Carr, but his star was rising. Less than two years later, now as Li-Kar, he headlined at Club El Rio in El Cerrito. “East Bay Gets a New Sensation!!!” heralded the advertisement in the August 8, 1940, Chronicle, describing him as “America’s Foremost Female Impersonator and Famed Interpretive Dancer. (S)he’s Beautiful! (S)he’s Terrific!”

As both Lee Carr and as Li-Kar, he continued at Finocchio’s for almost three decades. Onstage, he appeared as a dancer “specializing in dances of the Far East.” In 1943, the San Francisco Examiner described him as “one of the finest female impersonating dancers in the country.” Within a few years, billed as the “Famed East Indies Dance Impressionist,” he was appearing around the country in “his own authentic dance creations from the world’s concert stages.”

He was also making a name for himself as a costume designer. In 1940, Chronicle columnist Herb Caen wrote, “Gertrude Lawrence isn’t one to forget a pal. Among her guests at the Palace Tuesday night … was Lee Carr, a boy who works up at Finocchio’s. Last year, you see, Miss Lawrence admired a dress Lee wore in a show, so, because he had made it himself, he busily cut and stitched a copy for the star.” Tallulah Bankhead also was an admirer.

Eventually, the fashions Li-Kar created became one more reason to see the show. His “costumes are truly exquisite,” the Chronicle informed its readers in 1941. As late as 1958, the paper, always a fan, noted, “The style-conscious will be interested in the beautiful costumes worn in Finocchio’s lavish new revue,” designed by Lee Carr. In 1965, the Examiner reported that “Li-Kar holds the record for having created more new ideas in gowns for female impersonators than any designer in America.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on June 9, 2022

Recent Comments