By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

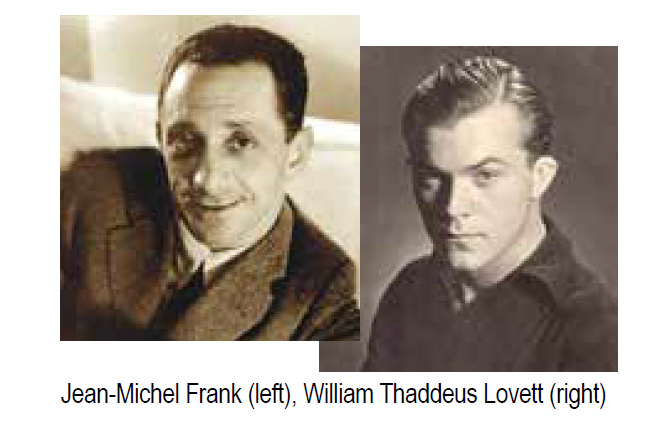

Ilsa Lund and Rick Blaine may have planned to take flight from Paris to Marseilles just ahead of Germany’s invasion of the city in June 1940, but theirs was not the only escape route away from the imminent Occupation. That same month, in a scene as dramatic as any in Casablanca, Jean-Michel Frank and his lover William Thaddeus Lovett fled the capitol for Bordeaux, only days before France fell to its enemy’s forces, hoping to secure visas to reach Portugal and then the United States.

The two men, who had been together for more than six years, both knew that Frank’s reputation as the foremost interior designer and decorator of his generation would not save him from a regime that was notorious for persecuting intellectuals, modernists, Jews, and homosexuals. Famous for his minimalist aesthetic expressed with expensive necessaries—his rooms were graced with simple furnishings made from the finest, rarest, most costly materials in the world—he personified everything they found abhorrent.

From the beginning of his career, Frank rejected the so-called opulence of Victorian interior design, with its mix of historical styles, eclectic furnishings, patterned wallpaper, maudlin pictures of childhood days fondly remembered, and objects d’art that had nothing to do with the room they cluttered. Deeply influenced by Eugenia Errázuriz, a famed patron of the arts who believed “elegance means elimination,” he embraced an ethos of radical simplicity, where even the most basic household items had straightforward, uncomplicated lines.

For Frank, “luxury was in the quality and not the quantity of the furnishings.” He covered interior walls with sheepskin parchment; fabricated curtains from raw silk; upholstered couches and chairs with Hermès leather; veneered tables with shagreen and straw marquetry; and formed lamps from forged iron, bronze, mica, and gold. As writer Maurice Martin du Gard noted, “Simplicity was becoming fashionable but, in fact, cost the earth.” Those who could afford such austerity quickly made him the most highly sought after decorator in Paris.

Frank’s 3,200-square-foot apartment in Saint-Germain-de-Prés showcased his minimalist artistic vision. None of the ten rooms contained anything except essential furniture: no pictures, few decorations. After visiting for the first time, Jean Cocteau remarked, “Charming young man. Pity he was robbed.” Even so, “le style Frank” became the must-have choice for high society. When he told clients that he was “willing to design our new apartment so long as we agree to get rid of most of our furniture,” they willingly agreed.

In 1926, a commission from influential art patrons Marie-Laure and Charles de Noailles made Frank the most important interior designer in France. To create a new interior for their mansion at 11 place des Etats-Unis in Paris, he stripped away the building’s elegant, gilded adornments, covered the walls with parchment panels, and furnished the great salon with items made from the world’s most luxurious materials. In 2019, The New York Times Style Magazine named it one of “The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design.”

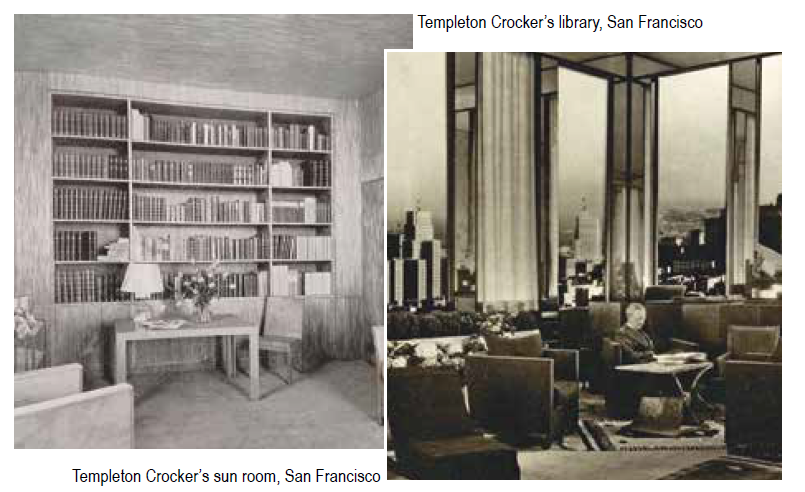

His next great project “brought Jean-Michel Frank to the forefront of the international scene.” In 1927, Templeton Crocker hired him to design the interior of his nine-room, 6,000-square-foot penthouse apartment at 945 Green Street on San Francisco’s famed Russian Hill. Mary Ashe Miller, writing in the August 3, 1929, issue of Vogue, described “the first large and luxurious apartment to be done completely in the modern manner in the United States” as “one of the most beautiful … in the world.”

Now the world’s most famous interior designer, Frank accepted only the most prestigious assignments for exorbitant fees: the music room of American songwriter Cole Porter’s Paris apartment; interiors for haute couturier Elsa Schiaparelli’s homes, headquarters, and boutique at 21 place Vendôme, where it remains; perfumier Jean-Pierre Guerlain’s salon on the Champs-Élysées; and Mary and Nelson and Rockefeller’s three story penthouse apartment at 810 Fifth Avenue, New York, completed in 1938, which was his last great commission.

Frank was 38 when he met Lovett, 19, in 1933. Theirs was “the strange union of a disenchanted German Jew, ‘dark, baroque, effeminate,’ and a Methodist Yankee,” Frank’s biographer Laurence Benaïm wrote later. Actually, he was from Corvallis, Oregon, where his father, Arthur Lester Lovett, had been Professor of Entomology at Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State University). With brown hair and hazel eyes, however, Thad, who stood 5’11’’ and weighed 160 pounds, truly looked like J. C. Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar man come to life.

The advancing war in Europe changed everything for the two men. No longer safe in Paris, they travelled south to Bordeaux, where they appealed to one of conflict’s greatest civilian heroes for rescue. Defying his government’s explicit orders, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the city’s Portuguese consul, issued thousands of visas to those fleeing fascism. Described by historian Yehuda Bauer as “perhaps the largest rescue action by a single individual during the Holocaust,” Israel declared him to be a “Righteous Among the Nations” in 1966.

Lovett and Frank received their endorsements on June 20, 1940, the same day as Gala and Salvador Dali and jeweler Marc Koven and his family, among others. Lovett and the Kovens sailed from Lisbon on the S. S. Manhattan on July 12, arriving at New York on July 18—traveling on the S. S. Excambion, Dali reached the city on August 8—but Frank, despite his famous American clientele, had to take a more daunting route, first to Argentina, then to Brazil, then to the United States.

When Frank finally arrived in New York in December 1940, he and Lovett, who was now working for Koven at his prestigious jewelry store at 17 East 48th Street, had been apart for six difficult months. Although they kept in touch during his time in Buenos Aires, interior designer Celina Aranz later remembered that Frank became more and more depressed and reclusive, especially “after terrible scenes, by phone, between him and his American lover.” Now Lovett told him that he had met someone else and their relationship was over.

Some blamed their breakup for what happened next, but Frank made it clear in the note he left on March 8, 1941, that as an ailing, despondent, stateless refugee who had lost everything to the war in Europe, he had chosen to leave this realm. “I do this for no reason but ill health. I ask all my friends who have been so good to me to forgive me. I thank them deeply for trying to help me, but I have no strength to go on.”

Apparently, Frank never met his cousin Anne, whose branch of the family moved from Germany to the Netherlands in 1933–1934, when she was four years old. Deported to the death camps of German-occupied Poland in 1944, she perished at Bergen-Belsen in early 1945; only her father survived the Holocaust. Her wartime diary, first published in 1947, has been translated into more than 75 languages, inspiring readers with its beloved messages of courage, strength, humanity, and hope in the face of adversity.

For different reasons, Jean-Michel Frank’s legacy also is assured. In her memoir Shocking Life, 1954, Schiaparelli wrote that Frank “invented a new style of furniture combining simplicity with considerable luxury.” More recently, Benaïm, whose biography of Frank appeared in 2017, stated, he “will continue to haunt our memories. Through his creations, he showed us the modernity of a point of view, impossible to reduce to a fashion or style. His force is to have opposed any form of theory or message—the ultimate truth of a dateless taste.”

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “LGBTQ+ Trailblazers of San Francisco” (2023) and “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on October 17, 2024

Recent Comments