By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

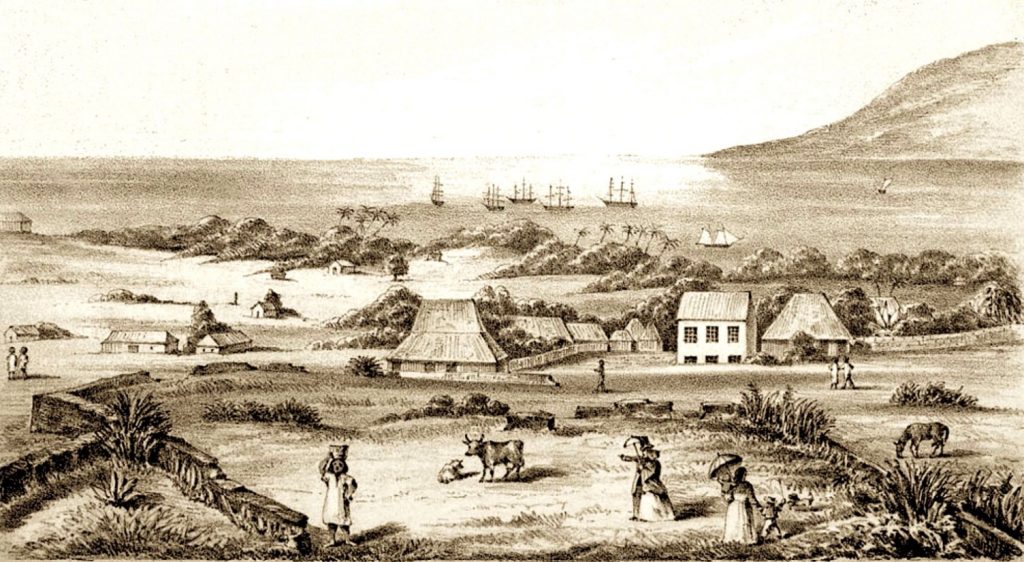

When Charles Warren Stoddard (1843–1909), San Francisco’s Lavender Boy Poet, visited the Hawaiian Islands in 1868, he was immediately taken with the beauty and the boys of Lahaina. For him it was not simply a whaling outpost that “had but one broad street,” but a place where “the sea lapped over the sloping sands on its lower edge,” a place of “soft night-winds” where “you could almost hear the great stars throbbing in the clear sky!”

For Stoddard, Lahaina was much more than “a little slice of civilization, beached on the shore of barbarism.” It was also a paradise where he could see “a young face that seemed to embody a whole tropical romance.” He had not intended to spend much time there, expecting “to catch a passage in a passing schooner.” The schooner, unfortunately, “flashed by us in a great gale from the south, and so I was stormed in indefinitely.” He soon had no regrets about remaining, however.

He found himself a “villa … built of dried grasses on the model of a haystack, dug out in the middle, with doors and windows let into the four sides thereof. It was planted in the midst of a vineyard, with avenues stretching in all directions, under a network of stems and tendrils.” Here he “inhaled the sweet winds of Lahaina, while the wilderness of its vineyards blossomed like the rose.”

Stoddard was equally infatuated with the people of the place. One night, he wrote, “when a lot of us were bathing in the moonlight, I saw a figure so fresh and joyous that I began to realize how the old Greeks could worship mere physical beauty and forget its higher forms. Then I discovered that face on this body—a rare enough combination—and the whole constituted Joe, a young scapegrace who was schooling at Lahaina, under the eye—not a very sharp one—of his uncle.”

Stoddard determined to know this young man better. He visited his uncle and “gave bonds for Joe’s irreproachable conduct while with me. I willingly gave bonds—verbal ones—for this was just what I wanted of Joe: namely, to instill into his youthful mind those counsels which, if rigorously followed, must result in his becoming a true and unterrified American. This compact settled, Joe took up his bed—a roll of mats—and down we marched to my villa, and began housekeeping in good earnest.”

Their life together was idyllic. “I used to sit in my veranda and turn to Joe (Joe was my private and confidential servant), and I would say to Joe, while we scented the odor of grape, and saw the great banana-leaves waving their cambric sails, and heard the sea moaning in the melancholy distance—I would say to him, ‘Joe, housekeeping is good fun, isn’t it?'” Indeed, it was. “We would take a drink of cocoa-milk, and finish our bananas, and go to bed, because we had nothing else to do.”

The two spent a great deal of time together, including “a night when we two walked to the old wharf, and went out to the end of it, and sat there looking inland, watching the inky waves slide up and down the beach, while the full moon rose over the superb mountains where the clouds were heaped like wool, and the very air seemed full of utterances that you could almost hear and understand but for something that made them all a mystery.”

Joe wanted to impress his employer in every way possible, which included dressing in the latest fashions. On the day Stoddard finally left Lahaina, “Joe came to the beach with his new trousers tucked into his new boots, while he waved his new hat violently in a final adieu, much to the envy and admiration of a score of hatless urchins … . When I entered the boat to set sail, a tear stood in Joe’s bright eye, and I think he was really sorry to part with me.”

Stoddard first told Joe’s story in the July 1870 issue of Overland Monthly, edited by Brett Harte (1836–1902), then included it in South-Sea Idyls, published in 1873. His accounts of Hawaii, wrote William Dean Howells (1837–1920), then “Dean of American Letters,” were “the lightest, sweetest, wildest, freshest things that were ever written about the life of that summer ocean,” completely ignoring their steadfast homoeroticism. Of course, Stoddard could not be explicit about his relationship with Joe—or anyone else—but those searching for his truth could find it.

Were he and Joe intimate in every way? Stoddard certainly was with other young Hawaiians he met. “For the first time I act as my nature prompts me,” he wrote about his visit in a letter to Walt Whitman in 1869, something that he claimed was impossible “even in California, where men are tolerably bold.” He never named names, however. As late as 1901, when DeWitt Miller asked him whether any of his island companions had been “Greek,” he simply replied that Joe had “seemed that way.”

Joe would not have been so coy about their love affair. The Hawaiians understood and enjoyed Nature’s infinite diversity and saw no shame in intimacy between two women or two men, known as aikāne. According to legend, same-sex relationships were an important and accepted part of Hawaiian life at least since the time of Wākea, the Sky Father, and Papahānaumoku, the Earth Mother, the forbears of the noho ali‘i o Hawaii (ruling chiefs of Hawaii). Many of the island nation’s rulers, including Kamehameha the Great, enjoyed aikāne in their households.

The Europeans, of course, were shocked, shocked that the Hawaiian royal family retained and enjoyed male concubines. David Samwell (1751–1798), ship’s surgeon during the visit of Captain James Cook (1728–1779) to the islands, wrote in his journal on January 29, 1779, “[It] is esteemed honorable among them and they have frequently asked us on seeing a handsome young fellow if he was not aik?ne to some of us.” By the time Stoddard visited Lahaina, the American missionaries were working very hard to suppress all such relationships.

Stoddard remained enamored with Lahaina throughout his life. Deeply sentimental, he remembered it as a place:

Where the wave tumbles;

Where the reef rumbles;

Where the sea sweeps

Under bending palm-branches,

Sliding its snow-white

And swift avalanches;

Where the sails pass

O’er an ocean of glass,

Or trail their dull anchors

Down in the sea-grass.

Perhaps not a great poet, he always evidenced a great heart, which the beauty and romance of Lahaina captured completely.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces From Our LGBT Past

Published on August 24, 2023

Recent Comments