By Beth Schnitzer—

To explore where the sport of figure skating is headed as the Winter Olympics approach, I spoke with Joel Goodrich, whose background as a competitive skater offers an insider’s perspective on the quad revolution, Olympic pressure, judging transparency, and why figure skating continues to captivate on the world’s biggest stage.

Beth Schnitzer: Before diving into the broader Olympic conversation, I’d love to start with your own skating background. Can you share your personal journey in the sport?

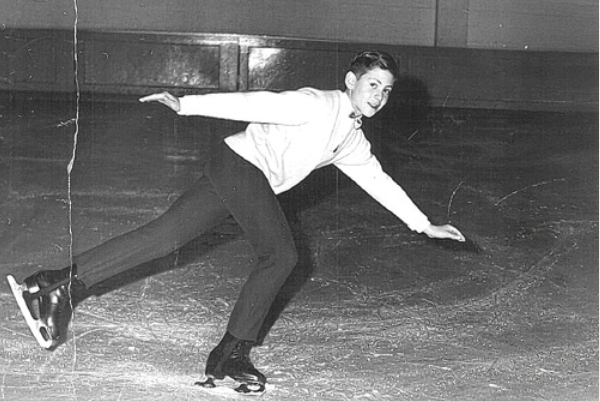

Joel Goodrich: My mother used to go skating every Sunday; she even had a skating outfit and her own skates. Then my dad and brother and I started to join her when I was about 7 years old. I guess I must have shown some aptitude because, pretty soon, I was skating after school then training before school. I loved the feeling of gliding across the ice, then the jumping and spinning all felt so natural and beautiful.

My family was living in the Oakland Hills, so I was training at Berkeley Iceland, which wound up being home to several Olympians and their coaches, so it was a great place to start off. I remember my first competition in the U.S. was at the legendary Sutro Skating Rink in San Francisco right above the iconic Sutro Baths—what an experience!

My family then moved to Paris where I was training with the French National Skating Team. The World Champion at the time, Alain Calmat, was French, so it was truly inspiring to be skating in that environment, Every summer we went to Chamonix in the Alps to train at high altitudes, and one winter we went to Megeve for a competition—it was such a magical environment.

We moved back to the U.S. when I was 13 and I competed at the national level during my high school years. Then came my freshman year at UC Berkeley, when I was hopefully going to compete at the senior level and try out for the Olympics. However, I was majoring in biomedical science (fortunately my brother became a doctor, so my mom was happy!) and had two jobs: playing piano 3 nights a week at Cafe Romano, and working at the front desk at the International House. This is a beautiful Julia Morgan-designed building for U.S. and international students where I was living. I realized I couldn’t have 2 jobs, major in bio-medical science, and try out for the Olympics, so I decided to quit skating and become a doctor or scientist. I never thought I would wind up back in skating, but a little thing called fate had something else in store for me.

Three years went by while I focused on my studies and my jobs. During that time, I was not on the ice a single time even though I had been on the ice pretty much every day while growing up. I remember dreaming I was going through my skating routine every night during those 3 years. Then came the second quarter during my senior year and I was applying to medical schools. I came down with what I thought was stomach flu. I ignored it as I was in the middle of final exams, but it turned out my appendix had burst and I had to go to the hospital and drop out that quarter. I thought to myself, I will just go back to school next quarter and re-apply, but it turned out quite differently.

The day after I got out of the hospital, I had an overwhelming urge to get back on the ice, I felt like I was missing part of myself. I was 20 years old at the time and it was like I had never stepped off the ice, I could still do some of the triple jumps—it felt exhilarating. Then, in one of those little twists of fate that totally changes the course of your entire life, I heard that Ice Follies was having tryouts that very afternoon in San Francisco. So, I thought to myself, “I’ll hop on BART and try out just for fun.” Well, I wound up getting a spot in the show and everything changed. I then decided I would join the show, then go back to school once I got back to Berkeley—well, it didn’t quite turn out that way.

The show I was in was going to Taiwan, so it was a fascinating experience both in terms of the performances as well as the culture. After 9 months of amazing adventures, I wound up back in Berkeley, but was immediately offered a coaching opportunity and never went back to school. I loved coaching, working with the kids and helping them succeed, not just in skating, but in their lives; it was one of the most rewarding experiences in my life. Not only did I help inspire them but also it inspired me in my journey ahead.

Four years later, the next chapter in my life opened up and I moved on. But many, many years later, a very wise friend of mine who knew the story said, “Sometimes an unexpected detour in life brings you to the place you’re meant to be.” And that’s exactly what happened.

Beth Schnitzer: What makes the Winter Olympics and figure skating, in particular, such a powerful global spectacle?

Joel Goodrich: Because it is such a beautiful sport in addition to its extraordinary athleticism, it is one that has universal appeal to many different cultures around the world. And the combination with music makes it even more compelling.

Beth Schnitzer: Figure skating continues to evolve—technically, artistically, and culturally. How have you seen the sport change over the past decade, especially in terms of athletic difficulty, scoring expectations, and the balance between artistry and technical precision?

Joel Goodrich: Over the past decade, figure skating has undergone a profound recalibration. Technically, the sport has become unmistakably more athletic: quads in the men’s field are now table stakes, women have pushed into triple axels and quads, and base value has become a strategic currency rather than a differentiator. The scoring system has reinforced this shift, rewarding measurable difficulty, execution, and risk management with increasing precision, while leaving less margin for purely reputational skating.

At the same time, artistry has not disappeared—it has been redefined. Programs today demand efficiency of movement, musical interpretation that complements technical layouts, and choreography designed to maximize transitions and component scores. The most successful skaters are not choosing between art and athleticism; they are integrating them seamlessly.

Culturally, the sport feels faster, younger, and more global, shaped by social media visibility and a broader range of influences. The challenge—and opportunity—moving forward is ensuring that innovation and difficulty continue to elevate, rather than eclipse, the emotional resonance that defines great skating.

Beth Schnitzer: American skater Ilia Malinin, the “Quad God,” is widely favored for Olympic gold. From a technical standpoint, how has Malinin redefined what’s possible in men’s figure skating, and how is his approach influencing both judging expectations and the next generation of skaters?

Joel Goodrich: Ilia Malinin has fundamentally recalibrated the technical ceiling in men’s figure skating. By routinely landing four, five, or even six quads in a single program—including the quad axel—he has transformed what was once extraordinary into a strategic baseline. Technically, his skating is built on exceptional rotational speed, air position efficiency, and repeatability, allowing him to manage extreme difficulty with a level of consistency rarely seen at this scale.

From a judging standpoint, Malinin has shifted expectations around risk versus reward. His success has reinforced the idea that programs anchored in maximal base value, when paired with solid execution, can create near-insurmountable scoring advantages. As a result, judges now evaluate technical ambition within a new context: not simply whether a quad is attempted, but how many, how difficult, and how reliably.

For the next generation, Malinin represents a seismic shift. Young skaters are training earlier for ultra-C (challenging) elements, designing programs around quad density, and viewing technical mastery as the primary pathway to global competitiveness. The sport has entered a new technical era, and Malinin is its defining catalyst.

Beth Schnitzer: Few stages bring pressure like the Olympics. In figure skating, where performance and precision intersect, how do athletes manage the mental and emotional weight of Olympic competition?

Joel Goodrich: It all comes down to skating from the heart. Being totally immersed in the artistic, as well as technical aspects of a performance, transports the champion skater into another world where the sole focus is to share the beauty of the sport with the audience. At the Olympic level, the difference between a medal and heartbreak for a skater is not just technical ability; it is the capacity to remain emotionally centered when the stakes feel absolute.

Beth Schnitzer: How do you assess the current state of judging transparency and trust in the sport, particularly in an Olympic setting where scrutiny is amplified? Do you think AI might play a role in judging at some point?

Joel Goodrich: Judging remains one of figure skating’s most scrutinized aspects, especially at the Olympic level where every call is magnified. The current system is more transparent than in the past, with published protocols, element reviews, and clearer criteria for execution and components. That said, subjectivity has not been eliminated—particularly in program components, where interpretation and reputation can still influence outcomes, fairly or not.

Trust in judging ultimately depends on consistency. When similar performances are rewarded similarly across events, confidence increases; when standards appear to shift, skepticism follows. The Olympic spotlight intensifies this dynamic, turning marginal differences into lasting narratives.

AI could eventually play a complementary role, particularly in objectively measuring jump takeoffs, rotations, edge usage, and under-rotation calls. However, it is unlikely to replace human judgment in areas like musical interpretation or performance quality. The most credible future model is a hybrid one: technology enhancing precision and consistency, with humans retaining authority over artistry and nuance.

Beth Schnitzer: Will you be going to Milano Cortina 2026?

Joel Goodrich: I will not be going to Milano Cortina this year, but will be watching. I don’t miss skating per se as the subsequent chapters in my life have been extraordinarily filling, but I am grateful for the foundation it laid for me to succeed—not just in business, but in living life in a purposeful and fulfilling way.

Final Thoughts From Beth in Snowy NYC

Being in New York for the Tournament of Champions Squash Championship offers a front-row seat to where global sport is headed. With Spritz on site managing social media, media partnerships, and more, alongside elite athletes on one of the sport’s most iconic stages, it’s a reminder that the Olympic journey is already underway, one match at a time, with many players here poised to represent their countries at LA28.

Signing off from the Bay—where passion meets the play.

https://milanocortina2026.olympics.com

Beth Schnitzer, the former President of WISE (Women in Sports and Events), is the Co-Founder and President of Spritz: https://spritzsf.com/

Beth’s Bay Area Sports Beat

Published on January 29, 2026

Recent Comments