By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

On a fateful afternoon, when Hazel, the pianist at The Black Cat in San Francisco’s North Beach, was playing arias from Carmen, one of the waiters began singing along in a strong tenor voice as he brought his customers their drinks. Soon he was performing four times a night, singing camp versions of then-popular torch songs, telling stories, chatting with people in the audience, reading them the paper, and commenting about reports of police harassment of the gay community, always wearing his signature high heels.

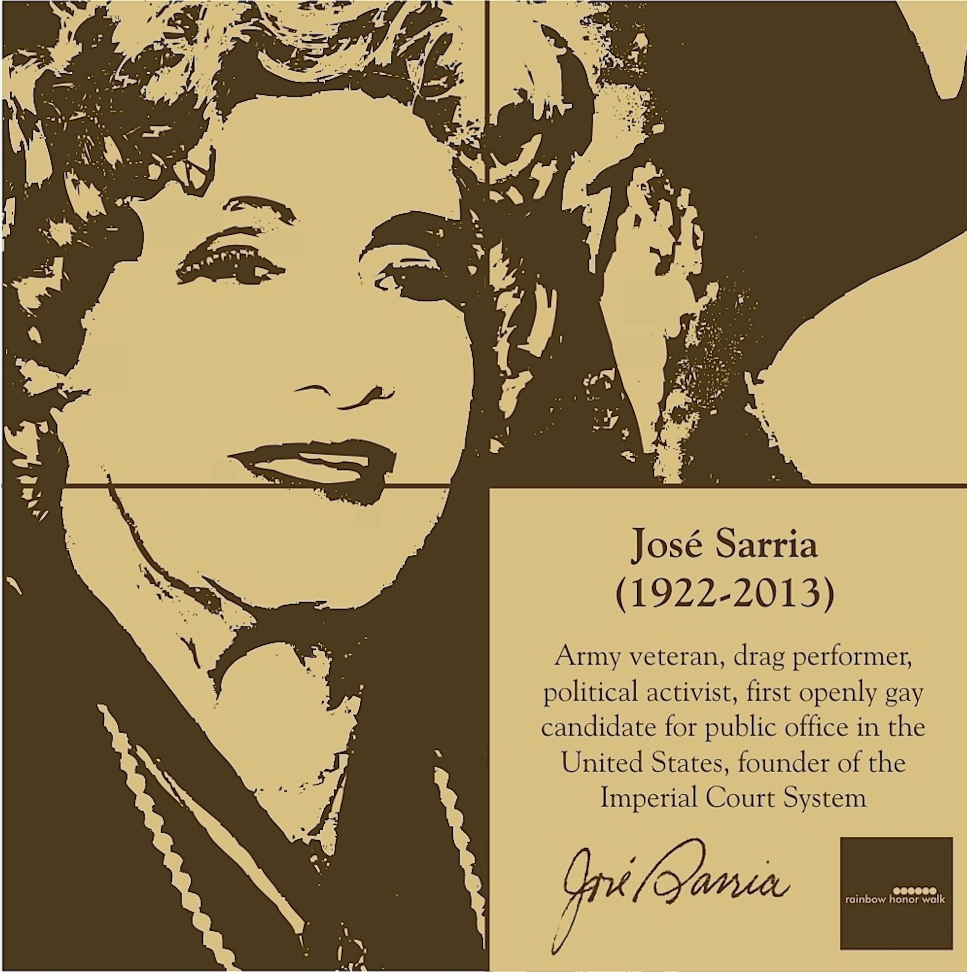

On such serendipity can the fates of peoples and nations be decided. José Sarria, whose 100th birthday we celebrate this December, had not planned to be either a performer or an activist. He wanted to be a teacher, but that ambition ended during a visit to the Oak Room of the St. Francis Hotel, possibly the only gay bar in San Francisco history whose manager did not know he was gay. So, instead he became the drag queen who changed the city’s LGBT communities and politics forever.

An elegant and discrete gathering place “for men only,” the Oak Room was advertised as having “an atmosphere designed for masculine comfort.” It boasted wood-paneled walls, a hand-painted ceiling, and a white marble floor, but the actual facility for masculine comfort was down the hall. One evening on a visit there, José was arrested, then convicted and heavily fined on a morals charge. He knew that a teaching career now was impossible. He turned to entertaining professionally “because I needed something to do.”

Soon known as “the Nightingale of Montgomery Street,” he continued to croon arias from Carmen that evolved into a Sunday afternoon extravaganza, one of his famous series of parody operas. Madama Butterfly was the first, but he also lampooned many others, including Aida, Tosca,and even My Fair Lady. Rewritten for a gay audience, they also highlighted some of the serious issues of discrimination and harassment it faced. Carmen, for example, now scrambled through the brambles of Union Square, not Seville, to avoid being arrested for cruising.

Overcapacity crowds adored these performances, even when José had in mind giving them more than a good laugh. At a time when the “experts” were telling them—and they believed—that they were mentally ill perverts, he wanted them to be proud of who they were and to stand up for their rights. He also shared some advice: “If you get tapped on the shoulder by a big blue star,” his Carmen told them, “say, ‘I’m not guilty and I want a trial by jury.'”

To forge both a sense of pride and a sense of community among the people in his audience, he had them stand up at the end of his performances, hold hands and sing:

“God save us nelly queens,

God save us nelly queens,

God save us queens, and lesbians, too.

From every mountain high

Long may we live and thrive,

God save us nelly queens,

God save us queens.”

“I sang the song as a kind of anthem, to get them realizing that we had to work together,” he told Gorman. “We could change the laws if we weren’t always hiding.” For many, including future activist George Mendenhall, Sarria’s message to be proud of who you are was “the beginning of my awareness of my rights as a gay person.”

In 1961, out and proud, José became a candidate for the city’s Board of Supervisors. He had no problem raising the $25 filing fee, but getting 25 signatures for his nominating petition was difficult. “Nobody wanted to sign any paper helping or saying that they were going to back a homosexual,” he remembered. He finally found either some “very bold queens” or some “closet queens who [I] had a little dirt on”—the story varied over time—and he was off and running.

Although he lost the election, José won some 6,000 votes, confirming his claim that the LGBT communities would come together for someone willing to fight for them. He also showed that there were enough votes in the LGBT community to swing an election to one candidate or cause or another in a close contest. He was the first openly gay man to run for public office anywhere, and his candidacy changed local politics forever. “From that day, at every election, the politicians have talked to us.”

The year José ran for supervisor he also co-founded the League for Civil Education, paying the startup costs for the new non-profit himself. The group survived for only two years, but the Society for Individual Rights, which followed it, lasted for almost two decades. Neither apologetic nor assimilationist, like some earlier homophile organizations, it opened a community center, sponsored social clubs, dances, candidates’ nights and theatrical productions, including its annual Sirlebrity Capades, at which José sang everything from arias to Edith Piaf.

In 1964, the recently formed Tavern Guild—the first LGBT business association in the United States—named José queen of its annual Beaux Arts Ball. Announcing that he was already a queen, he proclaimed himself Empress José Norton the First, in homage to San Franciscan Joshua Norton, who declared himself Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico in 1859. His first official appearance was a week later when he officiated at the opening of the Ice Follies.

A year later, Sarria founded the Imperial Court System, now the second largest LGBT organization in the world, with more than 65 chapters in the North America alone. As Her Royal Majesty, Empress de San Francisco, José I The Widow Norton, he remained active in the organization until 2007, then abdicated in favor of his heir apparent. When he died six years later, more than 1000 mourners attended his imperial drag-themed funeral at Grace Cathedral on Nob Hill, which he once had picketed.

José had been proven right. Affirming LGBT identity, inspiring pride, creating community, and building political visibility and strength were the means to effect change. Throughout his life as a performer and an activist, he made two truths clear to the LGBT communities. The first, “There’s nothing wrong with being gay—the crime is getting caught,” he said consistently until the anti-sex laws finally were repealed. The second, “United we stand, divided they catch us one by one,” carved on his tombstone, remains sage counsel to remember always.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on December 15, 2022

Recent Comments