By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

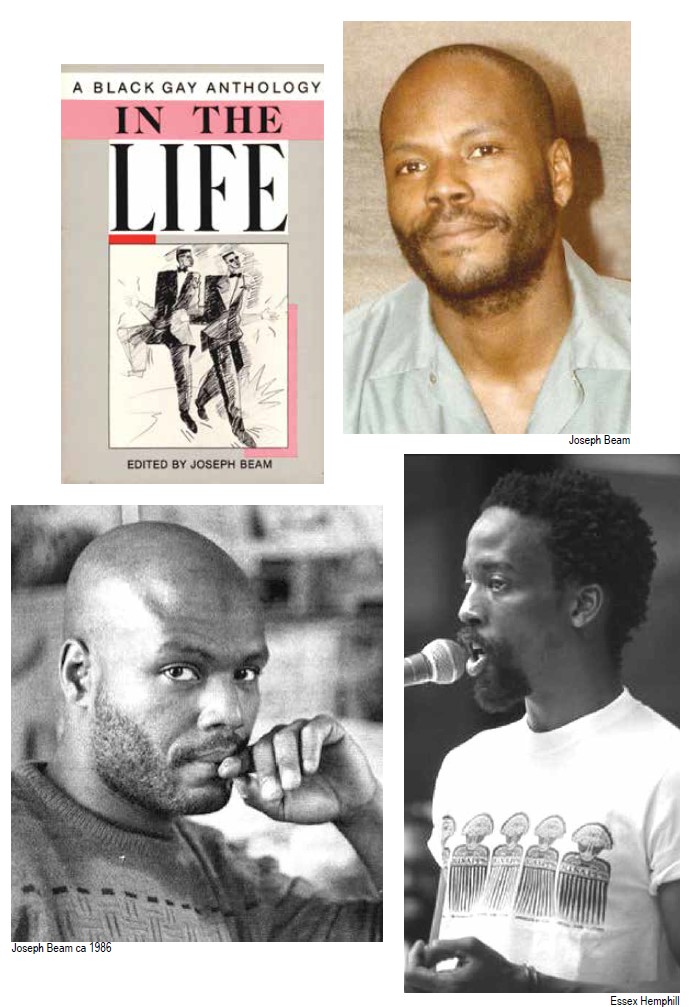

When Joseph Beam published In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology in 1986, the visionary writer and gay rights activist hoped to provide Black gay men “with crucial affirmations of their identities, their aspirations, and their desires.” With the stories, poems, and essays he collected for the work, he sought “to alleviate the alienation of Black homosexuals and help [them] create a community of their own.” For 35 years it has been that rarest of tomes: a book that changes lives.

In the introduction to his groundbreaking anthology, Beam explained the need for the book in no uncertain terms. “More and more each day,” he wrote, “as I looked around the well-stocked shelves of Giovanni’s Room, Philadelphia’s gay, lesbian, and feminist bookstore where I worked, I wondered where was the work of Black gay men.” They and their concerns were largely invisible to the larger Black and gay communities.

Beam simply “had grown weary of reading literature by white gay men who fell, quite easily, into three camps: the incestuous literati of Manhattan and Fire Island, the San Francisco cropped-moustache-clones, and the Boston-to-Cambridge politically correct radical faggots. None of them spoke to me as a Black gay man.” Out and proud to be both Black and gay, he wanted nothing less than create to a literature that brought “into the light the lives we have led in the shadows.”

In the Life did exactly that. “The words and images here—by, for, and about Black gay men—are for us as we begin to end the silence that has surrounded our lives, as we begin creating ourselves, as we begin to come to power,” Beam wrote. “The bottom line is this: We are Black men who are proudly gay. What we offer is our lives, our love, our visions … . We are coming home with our heads held up high.”

For Beam, the need was serious and immediate, even threatening. “We are the poor relations,” he wrote, “the proverbial black sheep, without a history, a literature, a religion, or a community. Our already tenuous position as Black men in white America is exacerbated because we are gay.” It was vital, he believed, for Black gay men to affirm their lives and share their truth with others because, “Visibility is survival.”

A showcase for new literary talent, a source of inspiration for its readers, and a literary and cultural milestone for the gay community, In the Life advanced that visibility. “For the first time,” wrote James Charles Roberts, a contributor, “Black gay men got to tell about their lives and experiences in their own words.” African American Studies Professor Charles Nero later described it as “the first collective expression of African American gay identity.”

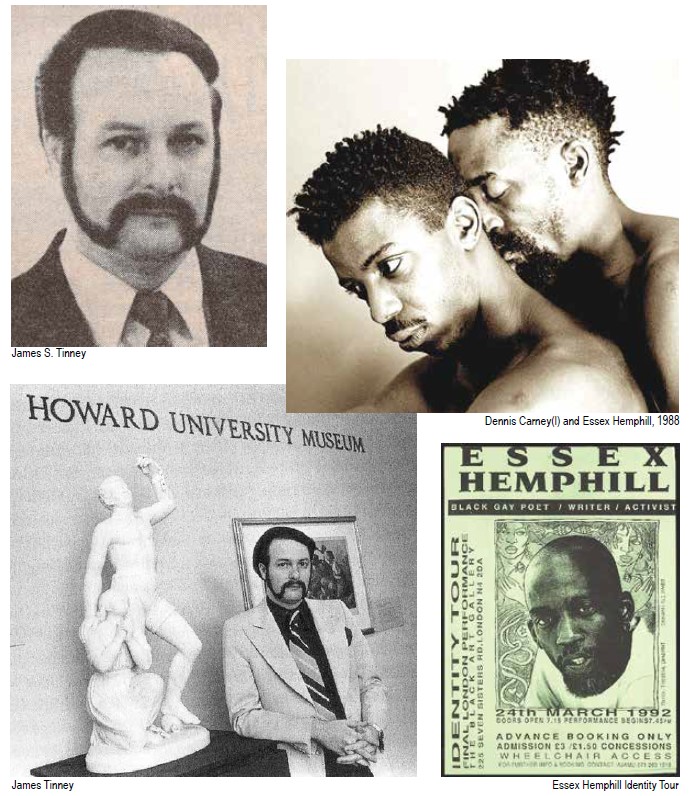

When James Tinney responded to Beam’s request for contributions, he was acutely aware of the need for Black gay community as well as the consequences of becoming visible. A leading authority on both the history of the Black press and Black Pentecostalism, he was deeply spiritual from an early age. He began preaching at Pentecostal revivals when he was 14 years old, became an ordained minister at age 18, and pastored churches in Arkansas and Missouri during his 20s.

After he married in 1962 and had two daughters, Tinney came to accept that he was gay. Partly because he wished to live in truth and partly because, according to The Washington Blade, “he found he loved a man he was secretly seeing,” he told “his wife and their minister.” They “rejected him and cut him off from family, children, and church.” The couple divorced in 1971. Tinney came out publicly in an address to the first National Third World Lesbian and Gay Conference in 1979.

Tinney never abandoned his Pentecostal beliefs. In 1982, when he was a professor of journalism at Howard University, he organized a three-day revival for lesbians and gays in Washington, D.C., “to reaffirm their faith and salvation in the church.” Soon after, he was excommunicated by the pastor of the church where he had been serving as a lay minister. The pastor stated publicly that Tinney “cannot be both Christian and gay.” Only if he denounced “the sin of homosexuality” could he be readmitted to church membership. Tinney refused.

Instead, he founded the Pentecostal Coalition for Human Rights and the Faith Temple Christian Church in Washington, D.C., a nondenominational congregation that he described as a “Third World lesbian/gay Christian church,” although all were welcome. Only some 12 people attended the first worship service in September 1982, but Tinney’s vision grew and endured as “a place to believe, belong, and become.” He died in 1988 of complications related to HIV/AIDS. He was 46 years old.

Beam also died of the consequences of HIV/AIDS in 1988, three days before his 34th birthday. His unfinished manuscript for a second anthology was completed by his close friend Essex Hemphill, “one of the most celebrated Black, openly gay performance poets of his generation.” Published in 1991, Brother to Brother: New Writing by Black Gay Men “is a community of voices,” Hemphill wrote. “Listen in because you’re family and these aren’t secrets—not to us, so why should they be secrets to you? Just listen. Your brother is speaking.”

One of only a handful of contemporaries to consider openly what it meant to be both Black and gay, Hemphill candidly examined race, identity, and sexuality in his work. He refused to be defined by his orientation, however. “Homo sex did not constitute a whole life nor did it negate my racial identity,” he wrote. He preferred to “integrate all of my identities into a functioning self, instead of accepting a dysfunctional existence as the consequence of my homosexual desires.”

Like Beam and Tinney before him, Hemphill too was lost to the ravages of HIV/AIDS. He died in 1995, only 38 years old. Like that of Beam and Tinney, his work is a testament to the power of words to change lives. As for them, his life is a testament to the personal liberation that comes to those who are their own true selves.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on July 15, 2021

Recent Comments