By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

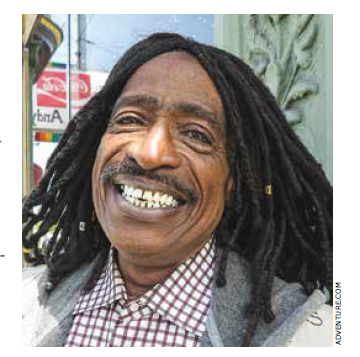

When Ken Jones moved to the Castro 50 years ago, the world, the city, and the neighborhood were very different places. Known even then as a gayborhood that attracted thousands with promises of openness, acceptance, and sexual freedom, the Castro also had a reputation for not being welcoming to many women or people of color. Jones remembered that, as a Black man, he still felt comfortable living there as a “neighborhood regular,” but over time he realized that progress required LGBT activism to “look just like our community.” He became, in his own words, “kind of the father of diversity.”

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, on November 9, 1950, Jones moved to San Diego in 1969 to join the Navy. After surviving three tours of duty in Vietnam and being decorated for his service, he concluded his time in the armed forces at the naval base on Treasure Island. Honorably discharged in 1972 as a Yeoman First Class/YN1 (E-6), he moved across the Bay to San Francisco, where he rented an apartment at Noe and 18th streets in the heart of the Castro.

That same year, Jones joined the staff at UCSF as Manager of Grant Expenditures and Reports. In 1978, he met Konstantin Berlandt (1946–1994), who was working there as a data entry clerk. Unlike the homophiles of the 1950s and 1960s, who sought “mainstream” understanding and assimilation for the gay communities, Berlandt was a gay liberationist who advocated for direct political action and for change through visibility, protest, and confrontation, if necessary, for an “out of the bars and in your face” activism.

Berlandt came to liberation early on. While still a student in 1965, he wrote the first article about the gay community ever published in The Daily Californian, “2,700 Homosexuals at Cal.” During the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in 1970, held in San Francisco less than a year after the Stonewall Riots, he wore a bright red dress when he and other demonstrators interrupted the proceedings to protest the organization’s diagnosis of homosexuality as a “sexual deviation” and a “mental disorder.”

Now involved with the Gay Freedom Day Parade, Berlandt asked Jones for his opinion of a flyer for an upcoming committee meeting. “When I pointed out to him the lack of diversity in the all-white all-male images,” Jones later told the journalist Hank Trout, “he insisted I attend that meeting to discuss my concerns.” By the time it ended, he was responsible for “getting more underrepresented or non-represented segments of the community to march with the People of Color Contingent and to join in the parade planning process.”

1978, the year that Jones began volunteering with Pride, was pivotal not only for the organization, but also for San Francisco’s LGBT communities. It was the year that this newspaper, the San Francisco Bay Times, was launched. For the first time, Gilbert Baker’s rainbow flag debuted over the entrance to the city’s Civic Center. For the first time, Harvey Milk rode in the parade as the first openly gay man elected to public office in California, personifying that an LGBT person living an honest and open life could succeed. His assassination the following November devastated but also galvanized LGBT women and men everywhere.

Among the difficult tasks facing the organization was determining how to represent different LGBT communities in its name as well as its membership. Finally deciding to include both the terms “gay” and “lesbian” in the name of the parade—“gay” once applied to both women and men—it took months of conversation to agree upon the order they would take; the discussion about adding the term “bisexual” also was prolonged.

Jones became president of SF Pride in 1985, the organization’s first Black leader and one of the few people of color to lead any Pride organization. His hard work to make the group look more like the community by bringing “a majority of new, non-traditional members into the planning process” was showing success, but the challenges facing the group during his time in office, across some of the darkest days of the AIDS epidemic, were especially daunting.

At the same time, Jones volunteered at the Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation, created in 1982. After it became the San Francisco AIDS Foundation two years later, Jones served as Director of the Volunteer Services and Management. To enable the group to reflect the community’s diverse people and viewpoints, the same goal he had at Pride, he helped to form the Third World AIDS Advisory Committee. In 1985, the year he became Pride’s president, he also organized the group’s first 100-Mile Bike-a-Thon for AIDS.

Jones also became the Northern California Co-Chair of the California LIFE AIDS Lobby, established in 1986, and was “actively engaged in writing pro-LGBT legislation, lobbying, and killing bad legislation.” At the same time, Jones became one of the key organizers in the boycotts against the Castro bars that enforced discriminatory admission policies against women and people of color. The need to include all LGBT people in the community’s public affairs and places remained a goal across all his activism.

In 1989, Jones was diagnosed with HIV. Two years later, saddened and outraged by the police beating of Rodney King in Southern California, he left Pride to work for police reform. As his health began to decline, he participated less and less as an activist, but in the early 2000s he was again able to forcefully champion inclusion and equality. In 2009, after a BART police officer killed Oscar Grant, he was appointed a member of the Citizen Review Board for the BART Police Department.

To the end of his life on January 13, 2021, Jones gave of himself in whatever ways he could. An Ordained Deacon at San Francisco’s City of Refuge United Church of Christ, he officiated at weddings all over the world and shared his unique knowledge, personal experiences, and insights about the city’s LGBT communities on guided tours of the Castro. His contributions to their progress toward visibility, equality, inclusion, and participation will endure, woven deeply into the fabric of place and people that is LGBT San Francisco.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Published on July 14, 2022

Recent Comments