By Dr. Bill Lipsky–

During those years of divine decadence before the Great War began in 1918, many of Europe’s rich and powerful artists, writers, businessmen, politicians, and members of the nobility were caught up in a series of delicious scandals and denounced for “depraved, vile, villainous” and often criminal intimacies. For men such as Baron Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, their connections allowed them to avoid severe punishment for their behavior, but often led to years of self-imposed, although luxurious, exile.

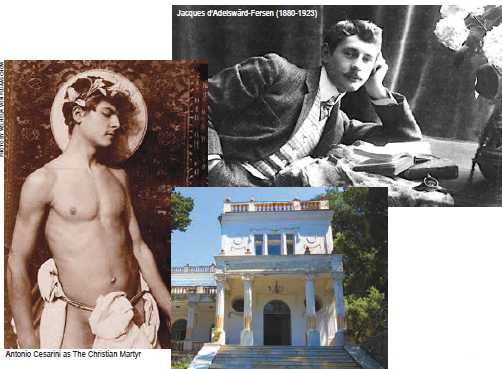

Tall, darkly handsome, imperially slim, and fabulously wealthy, d’Adelswärd personified the fading Romanticism of the 19th century, which rejected traditional social values to embrace emotion, individualism, paganism, pleasure, and a glorification of the past. Born in Paris in 1880 to a family of steelmakers, he added Fersen to his name as an adult in homage to Axel von Fersen, a Swedish count and distant relative who allegedly had a love affair with Marie Antoinette.

After a privileged education and a brief term of military service, d’Adelswärd considered going into politics, but decided to become a writer instead. No starving intellectual struggling in an unheated garret, he lived elegantly, driven around Paris by a liveried chauffeur in a royal blue Darracq automobile when only the wealthy could afford a car of any kind. He spent his days writing lavish hothouse poetry and slender lavender novels about beautiful young men and his afternoons and evenings perusing them.

In January 1903, d’Adelswärd leased an apartment on the Avenue Friedland in one of the most affluent neighborhoods of Paris; his mother lived just two doors away. Six months later, the French daily newspapers reported that he and his friend Albert François de Warren had been hosting parties featuring students “from excellent families” appearing in louche tableaux vivants, poses plastiques and a series of so-called représentations païennes (pagan representations). They called it “A Parisian Scandal.”

The parties quickly became “Orgies and Saturnalia” in the press reports. According to Gil Bas, the activities of the “two young Parisian gentlemen who hungered for novelty” soon “attracted the attention of the police [because] they were introducing the students of our lycées to the sort of homework that had only a distant relation to the kind the Education Ministry is recommending.” D’Adelswärd now was characterized as “un nouvel Oscar Wilde.”

Arrested on suspicion of indecent behavior and offending public decency, d’Adelswärd spent several months in prison, undergoing psychiatric examination before his trial finally began on November 28; the press and public were not allowed to attend. Five days later the court found him guilty only of the first offense. Given credit for time served, he was immediately set free, although he also paid a fine of 50 francs (about $10 then) and lost all his civil rights for the next five years.

Both French justice and Parisian high society were now done with him. No longer welcome at its salons and soirées, he considered joining the Foreign Legion, but finally was unable to “persuade himself to accept living together with people of a bad reputation as proposed companions.” He decided instead to relocate to Capri, a popular resort for those who enjoyed same-sex intimacies at least since the days of Titus, the 1st century Roman emperor.

Among d’Adelswärd’s contemporaries, the German painter Paul Hoecker (1854–1910), took refuge there after a scandal in 1897, when he was accused of using a male sex worker, with whom he was having a close personal relationship, as a model for the Madonna in his painting Ave Maria, now in the collection of the Neue Pinakothek in Munich. While on the island, he did a portrait of Nino Cesarini, the Baron’s lover, which hung in the Oparium, his favorite room.

The German industrialist and arms manufacturer Frederich Alfred Krupp also had a villa on the island. A close friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II, he spent his summers there, the last mired in a same-sex scandal. In November 1902, the German magazine Vorwärts published an article claiming Krupp not only was homosexual, but also had been sexually involved with numerous young men on Capri, including one Adolfo Schiano, an 18-year-old barber and amateur musician. Having returned to Germany, Krupps died a week after the allegations appeared in print. He was 48 years old.

Capri became a destination for many notable European homosexuals, including the writer and memoirist Faith Compton (Lady) Mackenzie (1878–1960), who lived there with her husband from 1913 to 1920, during which time she had an affair with the Italian pianist Renata Borgatti (1894–1964); Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) and two of his lovers, Robbie Ross (1869–1918) and Lord Alfred Douglas (1870–1945); and the English novelist Somerset Maugham (1874–1965), among others.

D’Adelswärd named his new home the Villa Lysis after one of Plato’s dialogues. While it was under construction, he took a trip around the world. On way back to the Capri, he met Antonio (Nino) Cesarini, a young construction worker then selling newspapers in Italy’s capitol. Later described by the Baron as “more beautiful than the light of Rome,” he became the great love of his life and his secretary as well, an appointment that frequently accompanied a passionate entanglement then.

In 1905 d’Adelswärd published Lord Lyllian, perhaps his most famous and important work, which satirized contemporary attitudes toward his decadent life. With a barbed epigram by Oscar Wilde on the title page—“Love for me has two enemies: prejudice and my caretaker”—it tells the story of a Scottish lord and his “wild odyssey of sexual debauchery” across Europe. After numerous, scandalous affairs, including one with a character apparently based upon Wilde himself, he dies a tragic death, of course.

When the villa was finally completed in July 1905, Nino placed the inscription stone, which proclaimed that it was “dedicated to the youth of love.” The two men remained together until d’Adelswärd died in 1923 after drinking a glass of champagne entangled with cocaine. His death was followed by a final scandal. Because he had left Nino a considerable inheritance, his sister accused Nino of poisoning her brother. Eventually, Nino returned to Rome, where he died in 1943.

Bill Lipsky, Ph.D., author of “Gay and Lesbian San Francisco” (2006), is a member of the Rainbow Honor Walk board of directors.

Faces from Our LGBT Past

Published on January 26, 2023

Recent Comments